|

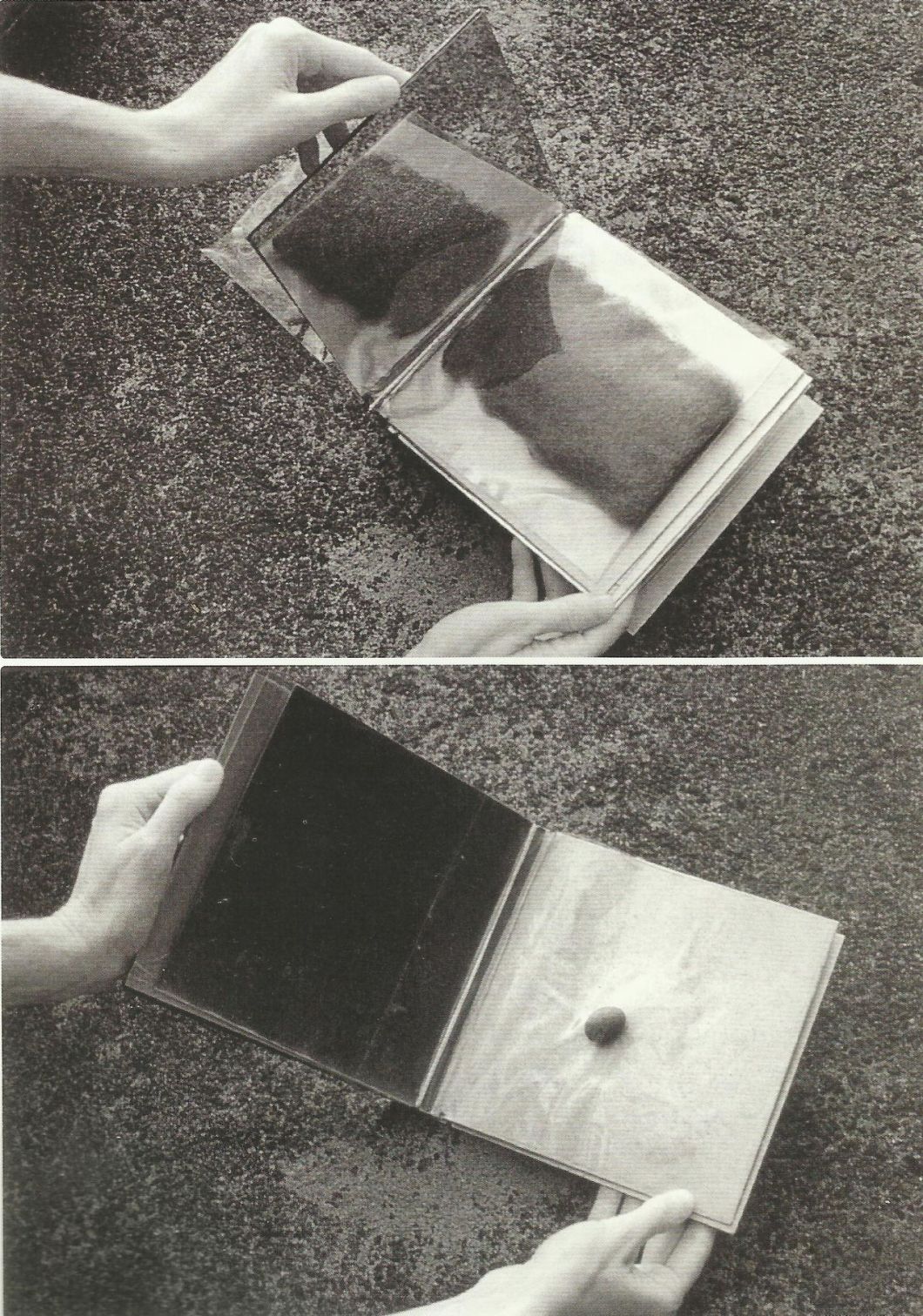

| Libro Sensorial, 1966 |

The picture on the backdrop of this blog is of Lygia Clark’s “Libro Sensorial,” a book made in 1966 containing a plethora of objects such as sea shells and stones, designed to create a tangible and interactive “reading” experience. During my recent MA, I looked into how the notion of the “organic” could be seen to develop in relation to both Clark’s paintings and sculptures, through to her more participatory later work. I delved into the artist’s writings in relation to her practice as well as critical ideas surrounding it, especially exploring bodily metaphors in her letters and diaries. As I found the topic so fascinating, I thought I’d share some of my research on here. In 1947, Moholy-Nagy wrote that the “problem of our generation is to bring the intellectual and emotional, the social and technological components into balanced play; to learn to see and feel them in relationship”. This struck me as particularly poignant in relation to Clark, whose work prompts an awareness of the interrelational, profoundly implicated in the agency of the participants.

|

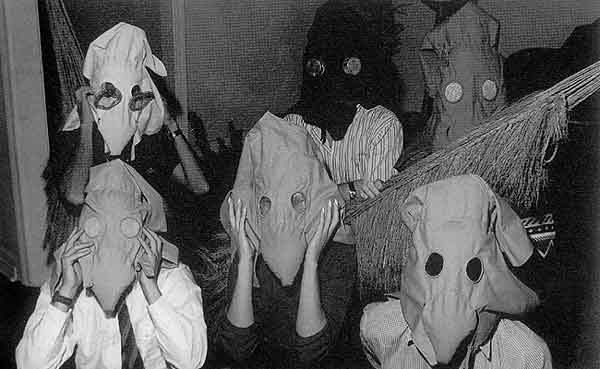

| Dialogue Goggles, 1968 |

Clark, born in Belo Horizonte in 1920, is well-known for being involved in the Neo-Concrete movement, which originated in Brazil and reacted to the “non-figurative” geometric leanings of “neo-plasticism, constructivism, suprematism” and sought to reintroduce expression into the work and for the “privileging of the work over the theory”. The poet Gullar’s Neo-Concrete Manifesto (1959) describes the work of art as a “quasi-corpus” and compares it with a “living organism,” capable of emergent meaning beyond its materiality. The notion of a work’s organicity, here, is also linked with the imaginative; Gullar writes that geometric shapes are “vehicles for the imagination”. This suggests that the organic lies not in the material alone but in its dynamism as part of an imaginative process between the artist and the viewer. However, while Clark was linked with Neoconcretism, she also wrote extensively about her own work; her writings offer incredible insights into the ways in which she conceived her practice.

In 1954, Clark began to formulate her idea of the “organic line,” a line which forms in between two squares of the same colour and disappears when the squares are separated. Clark demonstrates this with two black squares on a white surface, describing the line as vanishing when one square is removed, due to being “absorbed now by the contrast between the black and the white”. In this sense, the line is organic when it emerges in relation to that which is placed around it, as a sort of potentiality activated by the artist’s placement of materials and colour. In 1956, she began to use the term to describe “the lines appearing in the junction between doors and frames, windows and materials of the flooring etc.,” already existing in the “organisation of the space”. She called her Modulated Surfaces “an experimental field”, rather than an art work and writes that, one year later, she thought of the “line-space” as a “real constructor module,” suggesting that it can be used explicitly as part of the creative process. This brings to mind Albers’ idea that “probably the most important aspect of today’s language of forms is the fact that “negative” elements (the remainder, intermediate, and subtractive quantities) are made active”. The organic line, in this context, not only draws attention to the space between objects but is seen as a vital part of the experience of the work. Clark wrote that “demolishing the plane as a support of expression is to gain awareness of unity as a living and organic whole…the moment has come to reunite all the fragments of the kaleidoscope into which the idea of man was broken”. Here, the metaphor of the kaleidoscope might suggest a human experience of separation, dividing art and life, perpetuating a viewer/object dichotomy. The organic is related to the holistic, a state of being which does not privilege the idea of an elevated object.

|

| Lygia Clark. Planes in Modulated Surface 4. 1957, sourced from moma.org |

Malleability of form and the object’s dynamism are also linked with a developing concept of the organic in Clark’s work, which is illuminated by her writings on the Bichos. In 1965, she wrote:

“The Bicho has its own circuit of movements that reacts to the beholder’s stimuli. It is not composed of still, independent forms that can be indefinitely handled at will, as in a game. On the contrary, its parts are functionally related, as in a real organism. Their movement is interdependent.”

The idea of each moveable part forming a whole suggests that the organic is again linked with notions of the holistic, with connectivity being essential to the experience of the work (enabled by its hinges, in particular). According to Clark, the relationship between the viewer and the work involves active participation, with “no passivity”. The organic aspect of the Bichos seems to lie in the idea that the possibility for action is embodied within their design.

|

| Bichos (made between 1959-66) |

Similarly to the Bichos, the materiality of Clark’s book work Libro Sensorial (pictured on this blog) prompts a bodily experience which relies on the viewer’s subjectivity and interaction with the work to create meaning. Cornelia Butler provides a concise description of the work, drawing attention to the lack of text and that “each plastic page is the container for a topography of materials: the geometry of the book frames and is populated by organic and amorphous forms such as sea shells, stones, and steel wool, which communicate sensory experiences to the viewer”. This description brings to mind children’s books, with their presence of flaps and different textures enabling a playful sensory experience. Play, as with the Bichos, is part of the dynamic and the objects form part of a dialogue with the viewer; the book foregrounds them and suggests that the natural forms are capable of change according to the viewer’s action. The viewer’s own agency seems interlinked with the manipulation involved; this brings to mind Clark’s metaphor of the opening fist:

“At times I think that before we are born we are like a closed fist which opens its first finger when we are born and is opened internally like the petals of a flower as we discover the meaning of our existence, for us at a certain moment to become aware of this plenitude of an empty-full (interior time).”

The artist, then, helps to activate the already existing human potential for discovering meaning as part of their development. The presence of organic materials such as shells might connote a materiality which exists before humans assign the materials a practical purpose. Rather than presenting the viewers with already man-made objects which are likely to entail habitual responses, the simplicity of the materials could prompt a variety of reactions.

Clark’s Sensorial Objects also prompt a tangible experience; this is often part of a process of envelopment, which facilitates differing modes of interaction and experience. For example, her Sensorial Masks and Abyssal Mask invite direct participation and immersion in the work. The flexibility of the cloth and its loosely defined shape seem to prompt a playful dynamic with the object. For Clark, her masks are also connected to an experience of self-discovery. In a letter to Hélio Oiticica in 1968, Clark wrote:

I don’t even put on my masks or clothes and I always hope that someone will come along to provide a meaning to this formulation…More and more (Mário) Pedrosa’s phrase works in relation to my work: “the man object of himself.” You see, there is even greater participation. There is no longer the object to express any concept but rather for the spectator to more and more deeply reach his self. He, man, is now the “animal” and the dialogue is now with himself according to his own “organic-ness” and also in the sense of the magic he can draw out of himself.

|

|

Sensorial Masks

|

The idea of the organic seems to lie in an innate potential within the participant; the mask appears to prompt both an altered perception and a process of turning attention to the self.

Clark also refers to the organic in letters to Mario Pedrosa, particularly in relation to her feelings about her environment. In a letter written in 1972, she reminisces about a film called Gaulen, stating that its “bodily” architecture from the Middle Ages contained a staircase “as organic as an esophagus”. She writes that in the past the “house gave man the same habitat that the animal has in its involvement with nature, in which it blends in an incredible entity with branches, stones, earth”, as opposed to a more recently-developed “rational” architecture which offers “no protection”. The idea of the organic here seems to involve a return to a connection with the environment, as opposed to feeling isolated from it; her comparison suggest a yearning for a sense of interdependence between humans, architecture and the surrounding environment. This letter suggests that the importance of the organic for Clark persisted beyond her earlier works. She recalls her use of the term “empty-full,” and writes that “the body is the house of this space and that the more we become aware of it the more we rediscover the body as unfolding totality”. Much of Clark’s language in the letter connotes a sense of refamiliarising ourselves with our own bodies and potential, as if to counter a stultification of awareness.

This letter was written shortly before Clark started her course on gestural communication at the Sorbonne, during which students were encouraged to participate in a variety of experiences (which Clark called “propositions”). Elastic Net, as with many of the other propositions around this time, demonstrates the importance of the collective for this; made of elastic, the students were encouraged to form a net and immerse themselves in it. The interweaving of people and the material created the work and so evolved according to each individual’s action. Her use of simple materials also bring to mind Albers’ idea around “thrift”, where the artist tests the material to its limits; her works are often simply constructed in a way which might prompt the participant to explore this kind of process for themselves, collectively experimenting with the materials. Perhaps the political situation in Brazil around the time of this letter could be seen as fuelling Clark’s insistence on this collective experimentation and creativity. In her letter to Pedrosa discussed above, Clark recalls hearing the news that “returning to Brazil is now suicidal”. Anna Dezeuze, in her essay How to Live Precariously: Lygia Clark’s Caminhando and Tropicalism in 1960s Brazil, emphasises the brutality of the military regime in Brazil in the 1960s and writes that by trying to destroy “creative vitality” Clark was a proponent of, they “were feeding the very precariousness out of which resistance could be born” . In this sense, Clark’s propositions could be seen to establish modes of co-existing which incorporate the creative and the unknown, as opposed to dictating particular actions according to a system.

|

| Elastic Net, 1974 |

Exploring the relevance of the organic is particularly problematic in relation to Clark’s later works and practice. Clark wrote in the mid-1980s that her objects were not works of art, but prioritised the “act of feeling”. The development of her therapeutic work introduces further complications; Guy Brett discusses the difficulty of defining her later activity as either art or psychoanalysis, as both are part of “established practices” which her work does not sit comfortably within. However, Brett also posits that the object “continues in a new way her lifetime investigation of the relationship between the real and the imaginary, the inner and outer, the subject and object”. Clark’s therapy involved physical interaction between herself, the client and “relational objects” such as pillows and bags filled with air. The importance of experiencing holistically is suggested by Clark’s idea that the “body experienced as partial or fragmented becomes whole: the ‘holes’ in the body close up”. In this sense, the process deals with feelings of disintegration or disconnection, the relational objects being seen as part of the healing process.

Clark’s writings suggest that the notion of the organic often connotes a sense of the human capacity to imagine and create, using the pre-existing potential of matter. Her “organic line” posed a rethinking of “negative” space, foregrounding it through the organisation of the materials used; the dynamism of the Bichos prompts a dialogue with the viewer. In her increasingly participatory works, Clark placed emphasis on subjective experience created during interactive play. The abstract quality of her works seems to lie in the way in which they invite the participant to create their meaning, as part of a tactile process. Clark’s metaphor of the “closed fist” opening seems particularly apt to summarise the significance of the organic; the materiality of the works elicits a multiplicity of meanings, unfolding as the subject and object interact.

Gemma Cantlow

Bibliography:

Albers, Josef. “VI. Internationaler Kongress für Zeichnen, Kunsterricht und Angewandte Kunst in Prag, 1928” in Bauhaus, ed. Stein, J., trans. Jabs, W. and Gilbert, B. MIT Press, 5th printing, 1981.

Brett, Guy. “Lygia Clark: The borderline between art life” in Third Text (1987). 1:1, pp. 65-94.

Butler, Cornelia. H. in Lygia Clark: the abandonment of art, 1948-1988, eds. Butler, C.H. and Pérez-Oramas, L. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 2014.

Clark, Lygia. Lygia Clark: the abandonment of art, 1948-1988, eds. Butler, C.H. and Pérez-Oramas, L., trans. Landers, C. and Olivetti, L.R. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art, 2014.

Clark, Lygia. The Discovery of the Organic Line. http://www.lygiaclark.org.br/arquivo_detING.asp?idarquivo=6 (Accessed December 2014).

Clark, Lygia. Various Writings at http://www.lygiaclark.org.br/biografiaING.asp (Accessed December 2014).

Dezeuze, Anna. “How to live precariously: Lygia Clark’s Caminhando and Tropicalism in 1960s Brazil” in Women and Performance.Vol.23: 2 (17 June 2013), pp.226-247.

Gullar, Ferreira, “Neoconcrete Manifesto” in Time and Place: Rio de Janeiro 1956-1964, eds. Filho, P. V. and Gunnarsson, A. Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 2008.

Moholy-Nagy, Laszlo, “Vision in Motion” in Bauhaus, eds. Stein, J., trans. Jabs, W. and Gilbert, B. MIT Press, 5th printing, 1981.

Rivera, Tania. “Ethics, Psychoanalysis and Postmodern Art in Brazil: Mário Pedrosa, Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark” in Third Text, Vol.26: 1 (2012), pp. 53-63.