ArtSeen

Tarsila do Amaral:

Inventing Modern Art in Brazil

On View

MoMAFebruary 11 – June 3, 2018

New York

“I want to be the painter of my country”

- Tarsila do Amaral

Exporting Tarsila do Amaral

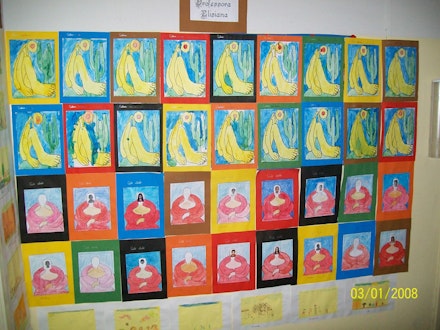

In Brazil, Tarsila do Amaral is a standard part of elementary school curriculum. Her work illustrates history books, literature exams, and is poorly copied in art classes. There, she is such a beloved and noteworthy figure that her surname is unnecessary. In the United States, George Washington Carver probably occupies an equivalent place in his country’s culture. Both became more of a myth than actual historical figures, their achievements obscured by their persona. Therefore, seeing Amaral in a one-woman show at MoMA was simultaneously exciting and unexpected—certainly causing a frenzy in the Brazilian artistic community.

Amaral’s most famous quote, “I want to be the painter of my country,” states her desire to represent Brazil in her art. Curators Luis Pérez-Oramas and Stephanie D’Alessandro fearlessly focus on her “Brazilianess,” highlighting her depiction of folkloric creatures, luscious greens, palm trees, and mulattos. Whereas it is true that Amaral was actively and consciously attempting to explore and create a Brazilian aesthetic, by the 1930s her work had become more socially engaged. Thus, the curators’ choice to only hint at her politicized side by displaying her painting Operários (Workers) (1933) in the very back of the last room, results in a gorgeous, yet one-dimensional view of an extremely complex artist. Certainly, it is difficult to exhibit such a prolific artist, and choices regarding time-frame and focus need to be made.1 What is troublesome however, is that the exhibition at times appears to present an exotic artist for foreigners, or as it is said in Brazilian vernacular, “para gringo ver.”

Although problematic, this foreigner approach does not compromise the exhibition’s quality, clarity, and organization. After encountering the quote previously mentioned and a life-size photograph of Amaral, the viewer faces A Cuca (1924) in its original Art Deco frame. The museum label uses the Portuguese word bicho (animal, critter) to refer to A Cuca, associating it to Lygia Clark’s seminal piece. This connection, although valid in a broader sense, seems inappropriate in this specific case and appears to be just a device for institutional self-promotion—MoMA presented a major retrospective devoted to Clark in 2014. The painting, which is isolated in this oblique passageway, depicts a mythological figure of Brazilian folklore, not an animal per se. In popular culture, such a figure is often described as fearsome. It is quite the opposite in her painting where the Cuca appears in tune with the other animals. The contrast between the playful representation of Brazilian folklore and the exuberant frame commissioned by the artist from the French designer Pierre Legrain, functions as a prologue to Amaral’s own identity. In the following room, paintings and sketches done while she was still a student in Paris culminate in her quintessential work A Negra (1923). Interesting parallels between her work and the Parisian avant-garde arise. While the artist had reservations regarding Cubism, the influence of Fernand Léger (her professor), Paul Cézanne, and others in her work is undeniable.

The seminal paintings Abaporu (1928) and Antropofagia (1929) can be simultaneously seen from where A Negra is displayed. While visually similar, the latter deals with controversial issues regarding race. The figure’s exaggerated lips and hanging breasts are used as symbols of her blackness, reflecting a racism inexorably present in Brazilian society. When Amaral was born, slavery was still legal, and even after its abolition, many former slaves still lived and worked on her family’s farm. Amaral, who was born into an extremely wealthy family, soon realized the racism embedded in her painting and avoided exhibiting it. Although racism is mentioned in the catalogue, unfortunately, the exhibition does not address racial issues enough. Conversely, in Abaporu and Antropofagia, the artist suppresses any racial controversy. Both paintings are respectively a cause and consequence of her interest in the idea of cultural cannibalism, promoted by her husband Oswald de Andrade in his Manifesto Antropofágico.

An entire room is dedicated to Brazilian Modernism, encompassing the Semana de Arte Moderna de 1922 (the Brazilian equivalent to the 1913 Armory show), the Grupo dos Cinco (a collective of artists, poets, musicians, and play-writers interested in creating a Brazilian avant-garde), and the Manifesto Antropofágico which promoted the idea of symbolically devouring the influences of foreigners, digesting, and transforming them into something innovative and Brazilian, as it was done literally by some indigenous tribes.2 Additionally, in the same area a display presents rare photographs and other memorabilia. This choice contributes to the educational aura of the show, underscoring the need to approach an artist who, until this point, was virtually unknown in America in easy-to-digest bits, rather than cannibalized chunks.

The show, which traveled from the Art Institute of Chicago, highlights Amaral’s drawings and sketches. This successful curatorial tactic emphasizes the precision and simplicity of the artist’s line so often overshadowed by her extravagant use of color and shading. Her relationship with the poet, playwright, and social agitator Oswald de Andrade is well explored through museum labels and documents. Unfortunately, the radicalism of her subsequent relationship—as a divorcée with a man twenty years her junior in 1940s Brazil—was not mentioned.

Everything considered, the show is a beautiful and lucid portrait of a short period in the artist’s career. It does what it proposes: presents Amaral as the painter of her country to an American audience who has never even heard her name before. However, as most introductions, it misses the complexities regarding gender, race, and politics encrusted in her life and work. Hopefully, as the dictionary definition of the word “introduction” suggests, the exhibition will be “a thing preliminary to something else.”

Notes

- There are no works from mid 1930s onwards, however she died in 1973 and worked consistently until the 1960s.

- Although Amaral was in Paris and did not participate in the Semana de Arte Moderna, her friends and colleagues were all part of the event.