A Short History of 1967’s “Summer of Love”

In 1967, San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district became the home base for a burgeoning counterculture. Known as the “Summer of Love,” the social movement was defined by a collective rejection of mainstream values and an embrace of ideals centered around peace, love, and personal freedom. An estimated 100,000 young people descended on the area; these artists, musicians, and drifters — collectively referred to as “hippies” — created an unforgettable cultural shift, touching everything from the way we view the self, to innovations in music, fashion, and art, and our approach to making an impact on society. More than 50 years later, the Summer of Love still dances freely in America’s memory.

The Summer of Love Actually Started in the Winter

Contrary to its name, the Summer of Love actually kicked off in the wintertime. In January 1967, in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, more than 20,000 people who shared a desire for peace, personal empowerment, and unity gathered for an event called the Human Be-In. It was a loud and proud harbinger to the blossoming counterculture movement set to congregate in Haight-Ashbury in just a few months.

The idea for the Human Be-In — also known as the “Gathering of the Tribes” — sprung from the similar, but much smaller, Love Pageant Rally that was held on October 6, 1966 — the day that California made LSD illegal. Organizers Allen Cohen and Michael Bowen, co-founders of the underground newspaper the San Francisco Oracle, wanted to re-create the peace and unity of that day, only on a larger scale. Their aim for the Human Be-In was to spread positivity and bridge the counterculture’s anti-war and hippie communities, while raising awareness around the pressing issues of the time: questioning authority, rethinking consumerism, and opposing the Vietnam War.

On January 14, 1967, the idea came together. Counterculture icons such as Beat poet Allen Ginsberg and LSD advocate Timothy Leary spoke to the masses — the latter famously urged participants to “turn on, tune in, drop out” — and the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and other legends performed at the event. The optimism that collective action could have a tangible impact on society felt stronger than ever. San Francisco Chronicle columnist Ralph Gleason said it was “truly something new,” calling it “an affirmation, not a protest… a promise of good, not evil.” The wheels for the Summer of Love were in motion.

Live Music Was Changed Forever

The Summer of Love not only introduced a cultural revolution — it also marked a turning point in pop culture. It made stars of some of music’s most enduring names and introduced major music festivals as we know them today. After the inaugural Human Be-In, other similar events unfolded around the world, laying the blueprint for large outdoor live performances. The first event to specifically call itself a music festival took place on June 10 and 11, 1967, on Mount Tamalpais in Marin County, just north of San Francisco. The KFRC Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival featured performances by the Doors, Jefferson Airplane, the Byrds, Steve Miller Band, and many others, and is considered America’s first true rock festival. One week later, another pivotal event — the centerpiece of the Summer of Love — changed live music forever.

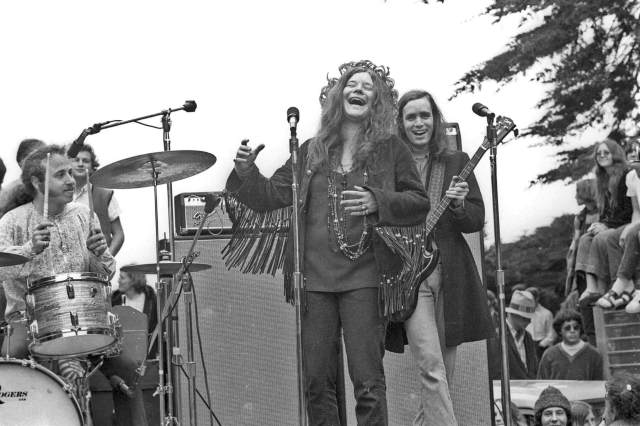

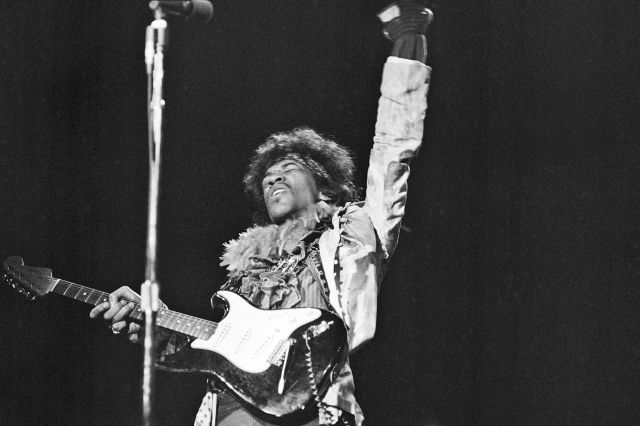

The Monterey Pop Festival took place across three days, June 16, 17, and 18. Organized by influential figures in the music scene, including John Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas, former Beatles publicist Derek Taylor, and record producer Lou Adler, the event attracted upwards of 200,000 attendees over the weekend. Prior to the festival, the release of “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)” by Scott McKenzie, a song penned by Phillips to promote the event, garnered significant global attention, becoming not only a chart-topping hit, but a driving force in enticing young people to join the hippies in Haight-Ashbury that summer. Press coverage turned Monterey Pop into a worldwide media spectacle. Iconic images from the event captured in a 1968 documentary by D.A. Pennebaker became lasting symbols of the hippie movement. The festival also catapulted artists such as Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Otis Redding, and The Who to fame, thanks to their legendary performances during that weekend. Monterey became the template for the modern festival industry, showcasing emerging artists alongside blockbuster bands in a massive outdoor setting.