Kweiseye is an art criticism blog written by Tom Kwei. If you enjoy this article, browse the archive here for more than 60 other critiques of both artists and exhibitions. Any questions/queries/use: tomkweipoet@gmail.com.

I’ve been writing Kweiseye for roughly half a year now. Initially starting as a mere exercise to ensure that I was continually learning about new artists, the blog six months later is now (in admittedly small numbers) read internationally, with the writings within leading to opportunities allowing me to share my own nascent artistic ideas in publications both online & physical. Kweiseye is changing then, and, in a way, so am I.

As prior to starting this blog my central interest in art derived from the desires of the image itself. What intrigued was the art taking place between the intended/unintentional message of the work and the viewer. And though this remains the centric thrust of my criticism herein, there is a new facet to each painting that I face that fascinates me slightly more. Its date. Its point of origin.

Fascinating not just because of where it positions the work on the grand scale of movements reacting to movements, but fascinating on account of the incongruity it can suggest. The works of Dutch Genre painter Jan Steen for example seem to fit entirely well with their 17th century marketplace, Tarsila do Amaral’s images however do not cohere with their 1920 point of arrival. They feel both pioneering and anachronistic for a post WWI work. Signs perhaps towards a sense of universal human experience. The shock of the new entrenched in the old. Whatever the education taken from it, her work is wildly original & creative. The two paintings featured today but the tip of the iceberg for one of the most influential Modernists in the history of Brazilian Art.

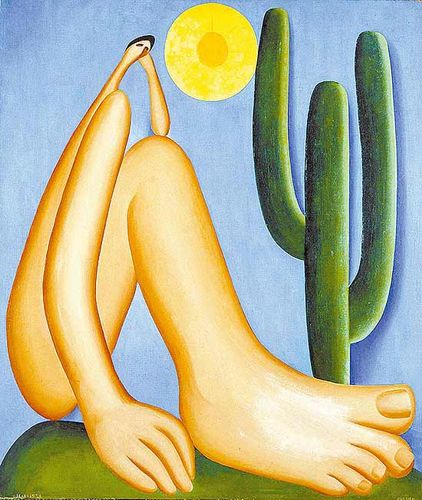

‘Abaporu’ – 1928

Originally a birthday gift to her then poet husband, Oswald de Andrade, this piece, whose title translates as, ‘The Man That Eats People’, eventually became the most valuable painting ever by a Brazilian artist, reaching the value of $1.4 million in an 1995 auction.

Whilst attempting to correlate the value of art with its financial estimation is redundant, it is perhaps worth focusing on why the image is so affecting, and, conceivably, why then it could be worth so much. For me it is that inspite of the fantastical imagery of this sexless, ageless, undressed giant, there is an exquisite sense of contemplation and humanity. Albeit one in which the soul of the sitter’s face is outshined by the very sole of the sitter.

The pose is classic. The image, of course, is anything but. Yet the stoic wondering is relatable to all. If it errs at all to the viewer, it is perhaps because ‘Abaporu’ perches itself upon a level of familiarity that disintegrates upon closer inspection. The limbs of the figure for example lack any connecting joints, with the pondering wrist a detached form, and the long leg up against the chest suggesting an uneasy stick torso if the eponymous people eater was to rise up. The cacti even appears more human than the man, its own arms suggesting a more recognisable pose, one in which a sense of division between composite parts is evoked with clarity.

Whilst the first internet-found image struggles to do justice to the sensuality apparent within ‘Abaporu’, I was lucky enough recently to have seen the work in person, able then to appreciate the real delicacy at the bottom of the work. It seems almost as two pictures really, the top an alarming abstraction of human form, the bottom a wonderful evocation of the same thing. The skin painted in such a believable and recognisable way as to draw us up back to the humanity that this thing embodies within its Rodin pose.

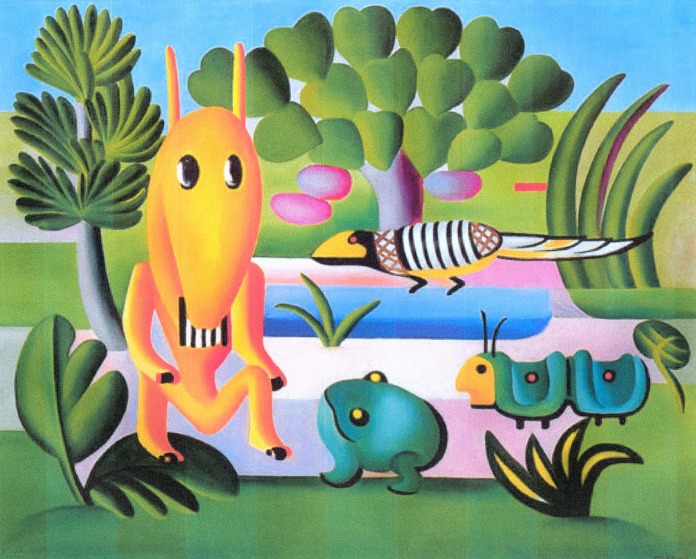

‘A Cuca’ – 1924

To draw back to my point from the introduction… how the hell is ‘A Cuca’ from 1924? This delightful, slightly unnerving image feels at least concurrent with current times in its psychedelic animal reimagining.

Regardless of the subtle chaos here, do Abaral, like in ‘Abaporu’, still creates an image of sensational technique. The smooth no-nonsense portioning of her brush working wonders throughout, giving all of ‘A Cuca’ a hazy, thumbed edge quality. One in which trees heave with heart-shaped leaves and tufts of grass spark high and aquiline.

There still seems a semblance of order here though, with the mad animals lining up in a sense around their own podiums within the animal kingdom. Frog, Caterpillar & Bird all looking towards whatever the central creature is, signifying their own biological obedience. The beast does just the same, looking out of the painting towards us, its simple, yet oddly disturbing eyes looking askew yet still face on. We are, in a sense then, above this world portrayed. But through do Abaral’s imaginings, the question of if we really understand it at all lingers heavy.

Enjoy reading that? Click HERE to see a list of all the art analyses on Kweiseye to date.

To keep up with the blog and all the art I write about, follow me right here on this blog or here @tomkweipoet