The Japanese writing system is … complicated.

Japanese as a language isn’t particularly difficult, no more or less than other languages, but its writing system demands considerable time and investment to really get comfortable with. Written Japanese comprises of a mix of a few different things:

- Hiragana syllabary1 – This is the default way of writing Japanese, and what most people, including kids in Japan, learn first. Note that hiragana characters are “syllables” not letters. One sound equals one hiragana character.

- Katakana syllabary1 – The katakana is a 1:1 analogue to hiragana. In other words, every hiragana character has a corresponding character in katakana, but katakana looks more “blockey”, less flowing, than hiragana. It is most often used with foreign words, Buddhist mantras, or just for impact (e.g. sound-effect words in manga).

- Chinese characters – Also known as kanji.

A typical sentence might look like: 今日はズボンを買った。Everything in blue is kanji, everything in red is katakana, while everything else is hiragana. I’ve spoken about the hiragana syllabary (part 1, 2 and 3) already, and katakana is similar enough that it does not require a separate article. So, today we’re just covering the use of Chinese characters or kanji.

Historically, China’s neighbors, such as Korea, Japan and Vietnam spoke languages that are both very different than Chinese, yet they wanted to import Chinese technology and culture. When they imported the Chinese writing system, however, it wasn’t an simple fit. Native words sound very different than Chinese, and sounds in Chinese language don’t always exist in the native language. Thus, Chinese characters’ sounds change when they’re imported.

Returning to Japanese language, the word for Japan in Chinese characters is 日本. In modern, Mandarin Chinese this is pronounced as rì běn, but in Japanese it’s pronounced as either nippon or nihon.2 This YouTube video helps illustrate the process:

You can see how the process of importing Chinese characters into Japanese was very organic. The result is that there are often many ways to read a Japanese kanji character, depending on whether it’s read in a native Japanese way, in a Sinified (Chinese) way.

The native way, or kun-yomi, is most often used for standalone words (not compound words), people’s names, place names, and verbs. For example, the kanji 山 is read as yama in the native way. When talking about a mountain, or in someone’s name such as Sugiyama, you would most likely see this native pronunciation.

However, the Sinified reading of this kanji is san or zan . This is the on-yomi reading, which you might see in a compound word like 登山 (tozan) for mountain climbing. It’s the same kanji character, but now it’s read as “zan” instead of native “yama”.

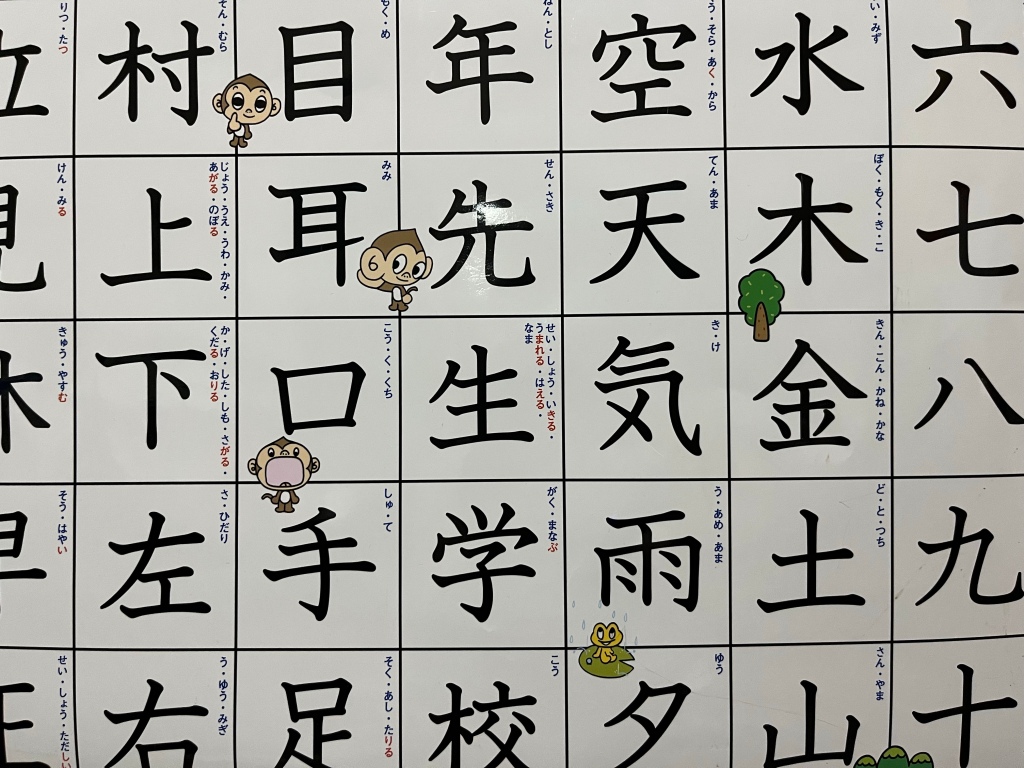

If you look at my son’s kanji poster above, you can see for each kanji there is a mix of kun-yomi readings and on-yomi readings. Some kanji (夕) have maybe only one reading. Some (下) have seven or more! It all depends on how it was imported into Japanese, and how it’s applied in the language over the centuries.

So, inevitably the Japanese language student asks: how am I going to learn all this kanji?!

Short answer is: you don’t.

Beyond maybe the first 100 kanji, the amount of time and effort to memorize the kanji rapidly becomes untenable, and you get diminishing returns. How many kanji have an on-yomi of shō ? A lot, too many to remember which is which. Also, the further along you go, the more obscure and specific kanji get, so the returns worsen over time. They’re important, but show up in increasingly specific contexts.

Further, using mnemonics or pictures to learn the kanji is only useful when the kanji actually looks like something, which is mostly the basic kanji only. The aforementioned 夕 does look like a moon at evening, so mnemonics work. But what about 優?3

Don’t get me started on the Heisig method. It’s a useful way for learning how to break down Kanji into discrete bits, but beyond that it doesn’t provide much value for the amount of work required.

No, the only way to learn kanji is to not learn them individually.

Instead, focus on building your vocabulary, and learn the kanji as they come up. I talked about this a while back as the “convergence method” but there’s no magic here. As you learn more vocabulary words, certain kanji come up often, and you’ll learn to anticipate their readings in future words. Sometimes you get it wrong, and that’s OK, other times you nail it perfectly.

But there is one other feature of Japanese you should leverage often: furigana.

Furigana is a reading aid often used for younger readers, and for language students by putting reading hints just above the kanji characters. For example lets look at the sentence above now using furigana: 今日はズボンを買った。

This is much easier to read. It still flows nicely in Japanese, but now we have the pronunciation hints (written in hiragana) right above each kanji.

If you find yourself embarrassed for relying on furigana, don’t be. This is how grade-school kids in Japan learn to read. This is how my kids (bi-racial Japanese-American) here in the US learned to read Japanese. In time, after seeing the same word 50 times, the reader doesn’t even need the furigana anymore, and can read without it, but it helps smooth the transition. When I was learning to ride a bike as a kid, I relied on training wheels, but as my confidence grew, I could ride without using them. The training wheels were still there, but I was riding more and more steady, so I hardly noticed when my dad took them off.

So, the key to reading Japanese well, including kanji, is to read native media that uses furigana. Many manga for younger audiences (including my favorite Splatoon manga), use furigana for all kanji characters and it makes the process of reading, plus looking up unfamiliar words, much easier. Even adult media uses furigana to help with more advanced, obscure words.

The point of all this is that learning kanji isn’t a slog of memorizing hundreds or thousands of characters, it’s more about learning to read vocabulary, preferably using native media. The latter approach is way more fun, and actually provides value in the long-run versus memorizing a bunch of kanji in isolation, then forgetting everything.

Chinese characters are great, and convey a lot of things that alphabetic systems can’t, but they are also pretty complicated and require considerably more ramp-up time.

P.S. if you use WordPress, this is how you add furigana to your Japanese text.

1 These are syllabary, not alphabets, because each character represents a full syllable, not a single consonant or vowel.

2 Side note, 日本 was used in other countries, like Korea and Vietnam, and their pronunciation differed too. Korean language pronounces it as Ilbon, while in Vietnam it’s Nhật Bản.

3 Confusingly enough, same pronunciation as 夕, by the way.