At an era of economic and industrial stagnation, the samurai spirit faces a period of decadence. Virtue is sacrificed in favor of self-aggrandization, self-worth, and personal survival. This is the Tokugawa era, where man must scrounge for the next scrap of food by offering up his dignity in return. Kazuo Koize’s Lone Wolf and Cub takes this period and paints it with such fine brushes of hyperrealism, diversifying its narrative so acutely by presenting each level of society from multi-perspective episodes. Whether it be crime bosses, peasants, the shogunate, gambling, even something as niche as rice plotting—Koize consciously makes an effort to find every cultural setting representative of the era and place it down on paper.

So too does Lone Wolf and Cub religiously follow its portrayal of samurai morality. While occasionally preachy, there is no doubt that Koize adeptly recognizes bushi and displays just how the age’s decline has influenced key persons, as well as those in cognitive dissonance with their beliefs versus their efforts to survive. Ogami Itto stands as a firm stamp onto the world with undefiled, raw bushido. The contrast between his archetype and the ever progressing world makes for a fascinating study on the value of honor in this warping society.

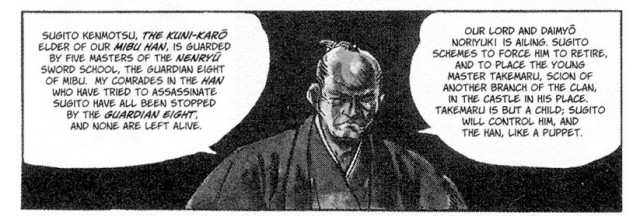

However, rarely ever sparing with words or mercy, Lone Wolf and Cub sure loves its high density of words and violence per panel. Despite manga being a visual medium warranting exposition through imagery more so than text, Lone Wolf and Cub‘s narrative imagines most of this at the hands of long, drolling speech bubbles, and blurred lazy motions to ostensibly indicate ‘action’. Entire paragraphs spanning four to five medium-long sentences per bubble is not uncommon, and the many exaggerations with respect to its violence, greed, and lust quickly become tiresome. The level of Lone Wolf and Cub‘s setting is nothing short of profound, but its outlet to do so is invariably lacking.

Unfortunately this effort for edification is also the second place where Lone Wolf and Cub goes wrong. In Koize’s attempts to bring excitement to an otherwise enduring textbook of words, words, and more words, the mangaka zips through a whole lot of action to inevitably contradict its accuracy at presenting a realistic world. This causes Koize to pervert the period with his own violent interpretation, brutalizing and sensationalizing the stereotypical violence and grit of the period as it suits him. While a work need not be realistic, the work is only disorienting and misinformative to readers by offering a very slanted view.

While there is also generally some subplot and context for each of the assasinations, they do little to build onto the overarching story, the characters, or the messages; the setting takes the forefront at the cost of every major element of the work. Many assassinations follow the same pattern with duplicate results, neither with any intriguing execution to enjoy from newly produced ones. Yagyu—the main villains of the story—stay on as just that: one-dimensional, greedy, and plain old “evil”. This even becomes undone with the inconsistent code of honor that the Yagyu follow, from backstabbing, poison, and feints, to halting the final battle in order to cooperate and save Edo. As the conclusions start to unravel, the work attempts to play the pity card on the Yagyu as if it weren’t their fault. Itto later defends Yagyu’s trickery as part of battle and of bushi despite his previous judgments of them as unbecoming of samurai. Not surprising then that as Itto plays as the refined mouthpiece of the author, Koize attempts to moralize the clan’s demise and uplift their sense of honor. Yet just so contrarily, the work depicts a fat, blunt-headed greedy old fart as the master poisoner, and goes at lengths to deride his “feminine” assassinations as plain cowardice, even though the Yagyu have long before burrowed further in “cheap tricks”.

To be fair, several episodes have indeed added more information besides the setting of the era: presenting new character background, new requirements to the missions, or new dangers. The wit of the battle strategies with how Ogami Itto manages to apply battle strategies from classics such as the Art of War is quite praiseworthy as well. Nevertheless, many battles are always left to a magical flair of voodoo, where samuraiman always survives unscathed and with flawless slayings with perfunctory movement; this inevitably comes down to whenever the mangaka has a good idea to solve a problem but cannot solve it all the way, and so he writes the wittiness in the former, and leaves the latter by having samuraiman massacre hordes and hordes of people (rending all that prior wit and strategy effectively useless). At several such glorious moments, Itto slaughters two dozen of Yagyu’s best despite being ambushed, and another with three of Kurokuwa’s while with a raging fever, and quite literally a wave of one hundred assassins. Nobody, not even Luffy, Naruto, or Ichigo, is that shounen good (!). This pulls away from any appreciation of the work’s technique; slap on some blurry motions and just assume Itto killed another with dat godfighting.

Yet, Lone Wolf and Cub‘s saga ends as a cathartic journey, with some excellent pacing after its fanfare with episodics. Some events end up as anticlimiactic—the whole five thousand ryo attained for little purpose, for example—but the sheer progress made across all 28 volumes is astounding with the way the work rarely loses its focus. This is a common pitfall among many long-running series, and it is a pleasant surprise to see this epic not forget its face.

Ogami Itto is set too high on a pedestal, undefeatable from the get-go having never failed a mission, and too perversely brilliant that the show seeks to glorify the character as a pivotal mouthpiece for the author. Even Itto’s backstory episode with his wife’s death offers no characterization of his family or clan, only heading towards laughable amounts of bloodshed and instant plot deductions made by the samuraiman. Let’s just say there’s a whole lotta self-insertion. And a bunch of magic voodoo with the way action choreography works and how he manages to kill so many. Whenever it does suit Koize’s purpose, Itto gets beaten, reverse-raped (!?), anything; and it never has a significant impact on any other part of the story, not even so much as a scar or wound hurting him for longer than the arc’s duration (he oughta at least lose some teeth). At one point, he and Daigoro get caught up in a sleep-inducing poison, while an onslaught of whores are around ready to pounce on him with knives. What does he do? Well apparently he’s so supernatural that he is able to deflect all of their attacks in his sleep! Could that figurative catchphrase get any more literal? That’s deus ex machina bullshit. Similarly, some of Daigoro’s chapters hilariously end with a similar in name solution, where Daigoro exclaims, “Papa!” and then the father always saves the day with his godhands.

Playing the cub of the duo, Daigoro is too precocious, too mature, too intelligent, and too pig shit deep in nihilistic samurai code. His three-year-old character oversteps the boundary of marginally acceptable realism and onto the feats of god ill-sent devil children. While the perpetual life of slaughtering may or may not condition a boy’s mind like this, these events do not account for the boy’s splendid genius and ruthless rationale—to the level of not accepting beggar’s food from samurai code despite not eating for three days, being flogged for helping a thief due to a flippant verbal agreement, or waiting weeks for his father in a shitty dugout fetching his own food and escaping near death on manifold accounts. No cowardice, no hesitation; just, his, eyes. There is no one that could turn so wise and so imperceptibly inhuman having lived only 36 months. A three year old would collapse in insanity before enduring such suffering. Personally speaking, I find this portrayal disgusting.

Much of the background dialogue is purposefully artificial, always explicitly providing the details and motivations behind keywords and plots, just so the audience is aware of them; this is of course despite the fact that the characters under the conversation are already well aware of them (this is a common trope among all typical shows for sure). This also loses much of the subtlety of the samurai’s action, as another character always spits out the convenience of explaining them in a future conversation with other nameless faces. When samuraiman expounds a quote from his famous spiritual author, another man must go on and explain what it means. This goes so far as to lose out on any deeper chacterization. Daigoro fishes alone to save his father from a raging fever, and there’s some crying couple narrating all his desire and love for his father by doing so. A samurai sees Daigoro’s shishogan and narrates as the boy hides in the mud from a fire, feeling incredulous at the boy’s inhuman genius. In general, the wordless father-and-son duo require too much the actions of others in order to leave everything blatantly stated out in the open. Indeed, these extras are practically what the author wants the readers to emote themselves, whether it be crying, or in awe at these two’s godlike physical and moral superiority.

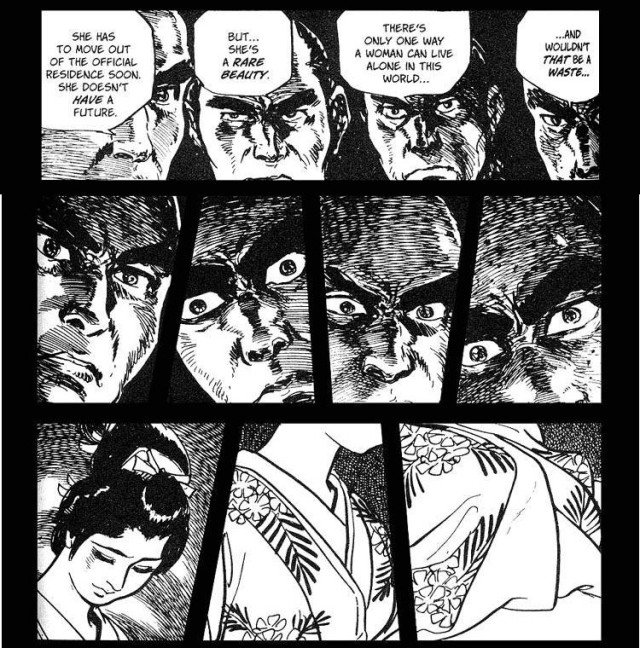

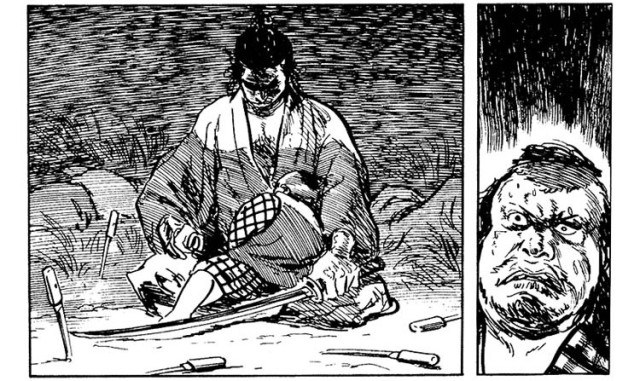

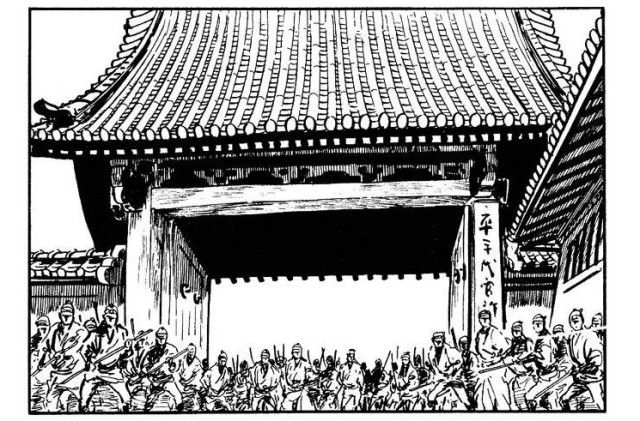

Visually, Lone Wolf and Cub is the codifier of its art style, featuring rough, often unfinished edges with a very dark texture and gritty detail. This works quite excellent with the desired hyperrealistic, yet partially exaggerated, actiony atmosphere. You know, gratuitous bloodshed because…seinen. This is also likely where the dramatic facial poses come in with a deep shadow masking half the face while the character says a supposed deep line or catchphrase. And MANLY tears: normal distinctively overshadowed and over-lined faces with a smudge of a tear drooping down their eyes. One of the most saccharine designs of the show for sure. There’s also some peculiar necessity to BOLD every other word of a sentence too.. This greatly disrupts one’s reading flow when there are so many emphases per sentence.

Lone Wolf and Cub shares the classic pitfalls of the semi-historical-but-not-really+samurai+seinen+battle genre. While it offers some decent worldbuilding, this most often comes at the cost of inordinate amounts of infodump. The episodics too offer little to substantiate the work past its setting and moralizing, instead offering a bland taste coming from gratuitious violence and mediocre characterization. While Lone Wolf and Cub is a must-read purely for seminal purposes, and its exploration of the Tokugawa period quite fascinating, I would restrain myself from calling it a masterpiece.

Score: Good (6/10)

Misc Comment on the education/history lessons:

I don’t know what to think of those expositions carried by long, enduring paragraphs outlining a piece of Tokugawa era culture. While it could be considered worldbuilding, to the already knowledgeable viewer this comes across as redundant, and the information written verbatim from textbooks regardless. Honestly, it’s a little lazy without incorporating its visuals as a supplemental teaching tool.

This is by far my longest review at roughly two thousand words. It started off as separate essays on different topics relevant to Lone Wolf and Cub, but I decided to give up on the affair and conglomerate them all into one fat wall of words. As a review itself, it goes on far longer than it should have, but these several thousand words are actually the result of cutting down almost twice its length. I will say that every word and sentence is (almost) always relevant.

I admire anyone who would read it all, as I’ve spent many hours doing concurrent analysis as I read the work and separate essays on the work. However, above all, I’d like to document this as a reference point given the very few criticisms of this classic that are available on the web.