It’s the middle of the World Cup, and I have to admit, I’m loving this soccer thing. Actually, I’m loving the men who play soccer. Have you seen those abs? Some of the team’s shirts are practically transparent. I approve of this sport. Soccer is amazing.

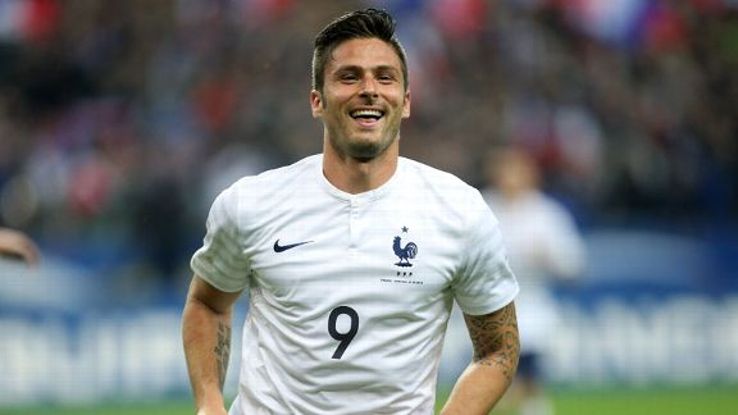

France’s Olivier Giroud – photo from espnfc.com.

My husband, who has been watching (and playing) soccer his whole life is looking at the action more than the hot players, bemoaning the histrionics of the Italian team (he’s Italian). They seem to fall down a lot. Even when no one has hit them or anything. I don’t get it.

But, Brian (the husband) does get it. He won’t stop yelling at the TV. And, when I was able to tear my eyes away from the visual splendor that is Olivier Giroud, I noticed that Brian’s muscles are tensing throughout the game as if he’s playing. My muscles – not so much.

Why is that? Is it because I’m too busy swooning over Mauricio Pinilla?

Chile’s Mauricio Pinilla – photo from Zimbio.

Not really. It’s a little thing called the mirror neuron.

In the 90s, Italian researchers wired up some monkey’s brains to see how their pre-motor cortex (the part of the brain that controls initiation of movement) fired when grasping for food pellets. When they ran out of food, the researcher had to pick up some more food pellets to place on the tray for the monkey. The monkey watching this activity had his brain fire simply from watching the researcher do the same motion the monkey had just done – lifting up the food pellet.

Mirror neurons – courtesy of a couple of lab monkeys enjoying a snack.

And, that, my friends, is how scientific discovery often happens. Accidentally.

What does this have to do with soccer? (Or football or whatever you want to call it?)

Apparently, we don’t always just observe other people’s action. We can feel it. And our minds can experience it as if it were happening to us.

Let’s say you see someone stub his toe really hard. “Ooouch,” you think. You cringe. You don’t feel his pain, but you kind of do feel his pain. Why? First, it’s something you know. You’ve stubbed your toe. You know it hurts. Second, you have special neurons in your brain – so-called mirror neurons – a type of brain cell that fires both when you perform an action but also when you watch someone else do the same thing.

My husband has performed the activities of soccer many times. His body knows it. His mind knows it, too. And his mirror neurons are jumping up and down, imagining they are performing the same movements (although my husband would point out that he would not have missed that goal…)

The mirror neuron system provides the ability to instinctively know what another one feels. And, it works best if you have a sense of what they’re feeling because you have felt it yourself.

I don’t react as much to the game itself as my husband does. Simply, my mirror neurons don’t know soccer. But what they do know is the excitement that winning elicits. Today, watching the game between the Netherlands and Mexico, I felt my heart rate increase when the Dutch scored the penalty kick that won them the game. I shared the excitement they demonstrated when they won. (I am a Dutch citizen after all).

What does this mean for the world of exercise?

If you’re a fitness teacher, it means that your students will inadvertently mirror your posture, so stand up straight.

It means all that air traffic controlling we’re doing while we teach (dropping our shoulders, lifting our arms as we tell our students to do the same, etc.) is a completely valid and necessary teaching tool.

It means sometimes demonstrating an action will get our students to do it better, not just because they got to see it, but because we’ve fired up parts of their brain that can improve their performances.

And it explains why, after a day of teaching, I feel like I got my own workout. Because I sort of did.

I’m going to go back to feeding my visual cortex pictures of soccer players. The brain does need its exercise.

In health,

Mariska

To learn more about neuroscience and exercise, sign up for our newsletter at the top of this blog.