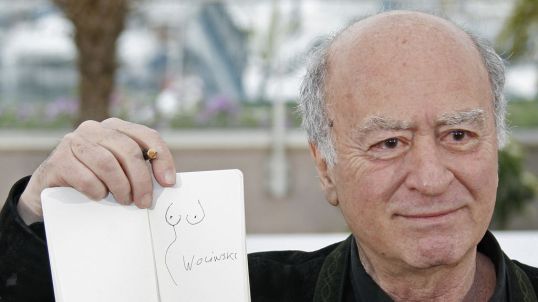

Georges Wolinski: ‘Virtue of His Contradictions’

Wolinski has played a significant part in demolishing what he calls the France of Marshal Pétain, whom he remembers having had to honour as a schoolboy. He is proud of the battles he has had with the censorship in the course of establishing the satirical magazines Harakiri and Charlie Hebdo. French law punishes not the distributors of ‘scurrilous’ literature but the authors and editors. That meant that personal courage was enough, commercial restraints were absent. He won the battles because he had a more powerful weapon: humour. He made the nation laugh at its own principles. But not the whole country, by any means. ‘Provincial France’ looked upon him and his kind as ‘intellectual terrorists’ and he admits to the accuracy of that description. He has been terrorizing those in power with his mockery, like a naughty child who pulls faces at a teacher. He was initially inspired by the cartoons of the American Harvey Kurtzman and the magazine Mad, but he has been much more radically satirical. Charlie Hebdo has been able to attack in a way that would be impossible in the United States, where subjects like religion may not be touched; Charlie Chaplin’s unpopularity in his later years, says Wolinski, shows that Americans refused to mock the very basis of their society. # Author

By Theodore Zeldin

It is Georges Wolinski, whose cartoons appear daily in the Communist paper L’Humanité, who has produced what is perhaps the most scathing contemporary portrait of the Average Frenchman. Flaubert, in the nineteenth century, wrote a Dictionary of Clichés, to ridicule the banalities of ordinary conversation, what people repeated to each other all the time. Wolinski’s caricatures add up to a similar treasury of what old fogeys today in provincial France, la France profonde, regard as wisdom. He has created two characters, whom he calls the Two Dinosaurs or the Two Idiots. They are always seated at a café table, with a glass of wine in front of each. The large one is vigorous in his denunciation of the imbecilities of the age and florid in his nostalgia for the good old days. The small one meekly and readily agrees with him, for he is easily impressed by his friend’s fine phrases and he wants to be respectable at all costs; his petty preoccupations, his efforts to please his wife, act as a kind of unanswered accompaniment, for the large one never listens to him.

The Two Idiots are stern believers in maintaining order. They approve of the Riot Police (the CRS): the large one says, ‘you must be fair: the CRS are quite different from the SS’. ‘They are only doing their job,’ echoes the small one. ‘Decent people,’ says the large one, ‘do not pay taxes so that the prison cells of bandits should be decorated like holiday resorts, with prison warders to serve them like waiters, a white napkin on their arm: A little more champagne Sir?’ The small one timidly suggests that perhaps not everyone in prison deserves to be there: ‘judicial errors do occur sometimes’. ‘Perhaps,’ his friend replies, ‘but I would rather have the prisons full of innocent people than the streets full of criminals.’

The pair are agreed that the trouble with the country is that the old inhibitions have been destroyed, ‘nothing is forbidden; the French have lost their sense of honour.’ For example, one of the large man’s cousins, who got engaged to a charming girl, happened to have syphilis. Everybody knew this, except the girl, because she was well brought up and did not know about such matters. So the marriage took place, no one said anything, and in due course they produced an idiot boy. But ‘honour was saved’. ‘Do you not think that is carrying the sense of honour a little far?’ ‘Monsieur,’ the large man insists, ‘that is how our families behaved in the past: there were no limits to the sense of honour.’ That is the one thing where he is glad there are no limits. ‘It’s lucky they’ve invented penicillin all the same,’ murmurs the small one.

But change is something both of them hate. They are appalled by the antics of the young. They protest at having to subsidize universities which are only schools for sexual orgies. They hate trade unionists, ecologists, Marxists, intellectuals, unmarried mothers and nude bathers, just as they cannot bear foreigners, Jews, the mini-skirt, abortion, lenient judges and divorced parents, sensuality and sociologists. They are suspicious of people who claim to have more talent than others: ‘If God had wanted men to have talent, he would have given talent to everybody.’ They look back to an imaginary age, when people were satisfied with their lot, when the unhappy man was content with his unhappiness, when even the leper was happier than the modern executive overworking so as to give the impression that he is rich. Like Voltaire’s absurd Dr Pangloss, they say fear is needed because without it there would be no religion; hate is necessary, because without it there would be no need for an army. Without ignorance, there would be no distinguished people, comme il faut, who were superior to the ignorant. Without shame we would all go about with naked bottoms. ‘As at St Tropez,’ chirps in the small one. ‘It is folly,’ says the large one, ‘to believe that one can make a society better than the people who live in it.’ In the olden days, every village knew who slept with whom, who among the mayor, the chemist and the lawyer, were sexual perverts, cheats or Nazi collaborators; but they managed to live peacefully together all the same. What is the point of new-fangled interference, and technocratic computers? They are suspicious of modern inventions, and of all people who are not suspicious. The thought of having to bequeath France to the intolerable young generation appals them. But to whom else can they bequeath it? asks the little one.

Wolinski has spent his life attacking these kinds of average Frenchmen, who are Colonel Blimp in England and ‘petty bourgeois’ in France. He is the enemy of taboos and principles, of the assumption that the poor do not want to live like the rich, or that women should keep their eyes lowered, that children should not speak at table unless they are spoken to, that pornography and drugs should be available to the upper classes only, and that the best jobs should be reserved for those whose parents had the best jobs. He has not invented these conservatives; they have had a part in his own life. His father was a small employer who was killed by his communist workers during the Popular Front of 1936. His step-father was a ‘typical Frenchman’ who read the right-wing Figaro and the sporting daily L’Equipe. He was brought up by his grandfather, a pastry cook, in the European quarter of Tunis. (It is important to remember that to the previous generation, France was not just a corner of Europe, but an international empire of a hundred million inhabitants; that a proportion of Frenchmen are a Mediterranean, not northern people, and that both the Archbishop of Paris and the leader of the largest trade union are of Polish origin.) Old-fashioned ideals of respectable family life were piously preserved there: the colonial French, the Jews, the Mediterraneans each kept to themselves, but they shared similar attitudes. In Wolinski’s childhood, women looked after the house, knitted, sewed and ironed, leaving the hard work to Arab servants; the men lived separately, going to the café to play cards and talk. Children were forbidden to swear and parents were careful to say nothing improper in front of them. The only rude jokes that were tolerated were about the bottom, excreting and farting, but not about sex. Wolinski discovered pornography by prising open a cupboard in which were kept the military decorations of an uncle killed in the war, and where he found the Decameron and Lady Chatterley secretly hidden. But he could barely understand them. He grew up chaste and prudish, and the chaste American films of those years, which he loved, suited him perfectly. It was only later on a motorcycling holiday in Italy that he discovered the joys of sex, in a Genoese brothel.

One of the great differences between that world and today’s world, for him, is that it is now possible to mention such subjects publicly. Fifteen years ago the male magazine Lui was banned for a photograph that revealed too much breast. Now sex is a frequent subject of humour, and major cartoonists have produced what in other countries would be labelled pornographic humour. Wolinski has played a significant part in demolishing what he calls the France of Marshal Pétain, whom he remembers having had to honour as a schoolboy. He is proud of the battles he has had with the censorship in the course of establishing the satirical magazines Harakiri and Charlie Hebdo. French law punishes not the distributors of ‘scurrilous’ literature but the authors and editors. That meant that personal courage was enough, commercial restraints were absent. He won the battles because he had a more powerful weapon: humour. He made the nation laugh at its own principles. But not the whole country, by any means. ‘Provincial France’ looked upon him and his kind as ‘intellectual terrorists’ and he admits to the accuracy of that description. He has been terrorizing those in power with his mockery, like a naughty child who pulls faces at a teacher. He was initially inspired by the cartoons of the American Harvey Kurtzman and the magazine Mad, but he has been much more radically satirical. Charlie Hebdo has been able to attack in a way that would be impossible in the United States, where subjects like religion may not be touched; Charlie Chaplin’s unpopularity in his later years, says Wolinski, shows that Americans refused to mock the very basis of their society.

But Wolinski does not represent the triumph of the new open-minded young France against the old France, which is an absurdly simplified contrast. Though he works for the official communist daily newspaper, he is not a member of the party. He feels most comfortable among the communists because he likes the warmth of their human relations, their unpretentiousness. Among socialists he meets too many well-educated people, who come from the same social background and the same schools as the Giscard technocrats, who are not his sort. The communists are more often self-taught like himself, rejected by their schools as hopeless failures; they have built up their own popular culture. Wolinski is not impregnated by the classics of French literature: as a boy, he liked American films and comics, English and American books, Edgar Allan Poe, Kipling, Jerome K. Jerome, Mark Twain, Fenimore Cooper. ‘No French book made me laugh as a boy.’ He believes he appeals to the same sort of ‘uncultured’ people, to the inhabitants of the working class suburbs, where dreary highrise buildings have very little that is French about them. He produces three books of cartoons a year, and he sells 50,000 of each, easily outdoing more fashionable novelists and philosophers. Altogether he has published thirty books. His first film was seen by one-and-a-half million people. He admits that working for the communists means there are subjects that cannot be mentioned; he has learnt instinctively to recognize what the party line is; but he feels amply compensated by the friendliness of his readers, whom he meets at party festivals. He likes them because they are not snobbish, they are not ascetics either, they want to enjoy a good life like everyone else; he finds their company relaxing. If he worked for a large circulation paper, he would hate the fierce competitiveness, the life with daggers drawn; in L’Humanité the quarrels are ideological, but there is less struggle for money, for careers. He once aspired to be in charge of an important newspaper, but he has now decided that he does not like giving orders, or being a leader. He values his independence most of all, which means he values the right to be himself. He has achieved that right, because he feels that he is now at last in power, in the sense that his generation, who were teenagers in 1960, have now become successful pop stars of one sort or another. Now they are accepted as part of the middle-aged establishment; they have achieved their victory.

Humour for Wolinski today involves lucidity on the one hand and provocation on the other. He does not think there are specifically national forms of humour. Humour is the ability to see through the veils of convention. Humour is dangerous because it can reveal everything as absurd, which is why so many comics commit suicide. But it is also a kind of maturity. Though he is so scathing in his commentary on the world, he lives very calmly in it. He does not get excited. ‘I have no complexes.’ He is amazed at the way his wife gets worried by minor problems. Everything is a worrying problem, he thinks, but that means that perhaps nothing is a problem. There is no saying what is a real problem, and even if one knew, one would not know how to solve it. It is best not to try to understand too much. ‘If you want to make mankind happy, start on yourself.’ He thinks happiness is not achieved by a policy of self-sacrifice and loving others: it is made up of mere moments of pleasure, as when a hungry man gets a bowl of rice; it is a smile, and a note on a guitar, the promise that one will not be tortured today, a cool hand on a burning forehead, and of course reading the works of Wolinski while lying on a sofa, eating a bar of chocolate. However, it is never quite possible to believe what Wolinski says: he refuses to avoid contradicting himself, since he thinks now one thing and now the opposite. His challenge to accepted ideas means that he can challenge his own ideas too: a person who has definite ideas, he says, becomes either a fascist or a believer. That makes Wolinski one of the most terrifying of humorists because he makes a virtue of his contradictions. For example, he makes one of his characters say: ‘If to be racist is not to like people who are different from one, well, then I am a racist.’ His defence is that truth needs to be exaggerated, and pursued to its extremes; by this means he shows that everyone including himself has something of the racist in him. His is a humour that seeks to destroy all defences, and not to spare his own. It is different from Bouvard’s cynicism, which is defensive; Wolinski is on the contrary a terrorist who blows up all certainties and himself in the process.

Behind his grenades, he is, of course, a quiet home-loving man, whose two main interests are his family and reading books. His little daughter trips into the room, saying she has a message for him; she kisses him and runs out. ‘Is that your message?’ The telephone rings all the time, but he knows it is for his wife, a journalist, who is Le Monde’s specialist on feminist affairs. He leaves it to her to answer. In his booklined study he seems cut off from the world, but he hates being alone. He and his wife, in nine years of marriage, have not spent more than three nights in separate beds. The one thing he has not succeeded in blowing up is the ‘phallocrat’ that resides deep inside him. He admits that when he married he treated his wife as a pretty toy; he says he cannot take women seriously because he always wants to touch them. He used to infuriate his wife by staring at other women: he tries to be more careful now, but he remains persuaded that if men have eyes, it is above all to look at women. He would give the sight of all the sunsets of Venice for that of a woman’s bottom. If one could weigh men’s staring at women, he says, how many kilos of stares would a woman count at the end of a day; and they would be stares weighing very different amounts, depending on whether they came from a Yugoslav window cleaner, an adolescent with complexes, a lorry driver whose cabin is full of pinups, or the woman hunter who is certain there is always one in a hundred who will respond to his advances. Wolinski is fascinated by all the traditional women’s stratagems: ‘I would be unhappy in a society that rejected flirting, high heels, transparent clothes, perfumes, and trousers that hug bottoms. I believe I am not the only one of my species.’ He is quite unable to get used to the new feminist theories, which is inconvenient, because his wife, having refused to remain the housewife he would have preferred her to be, has become a leading activist in the feminist movement. He insists that he needs to feel loved, to imagine that she regards him as an idol, ridiculous though that may be. She treats him rather toughly. ‘You really are the woman I need,’ he retorts, ‘because I have no will power; thanks to you, I appear to have it. Alone I would have spent my nights crawling round bars. I would have become fat, dirty and alcoholic. I believe that all that men do which is good, they do to try to impress their wives. What luck that there are wives.’ But it is becoming more and more difficult to impress them. Men are becoming more like teachers whose pupils suddenly laugh at them. To laugh at his teachers was precisely what Wolinski did in his youth. So, ultimately, he is proud of his wife being what she is, and he is sorry for all those women who are not fortunate enough to have a husband as nice as himself. Having thrown grenades throughout his life, he is bemused by the fact that he has been standing on a feminist grenade all the time.

His two-volume history, France 1848– 1945 (1973, 1977), received international acclaim: The Times called it “brilliant, original, entertaining and inexhaustible”; Paris Match said that it was “the most perspicacious, the most deeply researched, the liveliest and the most enthralling panorama of French passions”. His other books include the novel Happiness (1988). Theodore Zeldin has been awarded the Wolfson Prize and figures on Magazine Littéraire’s list of the hundred most important thinkers in the world today.

Excerpt from Theodore Zeldin’s Book ‘The French’ (1983)