Editor’s Note: Frida Ghitis is a world affairs columnist for the Miami Herald and World Politics Review. A former CNN producer and correspondent, she is the author of “The End of Revolution: A Changing World in the Age of Live Television.” Follow her on Twitter @FridaGhitis. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

Frida Ghitis: Is it OK to watch World Cup games while the world is in strife?

She says people everywhere take a break to bask in the emotion of the games

There's a long history of sport being a harmless way to express rivalries, she says

Ghitis: It's just a game, but the emotions are real

Is it wrong to watch football while the world’s on fire? Is it wrong to love the World Cup, to get excited about a goal scored in Brazil while there’s mayhem in Iraq, destruction in Syria, Russian troops massing near Ukraine?

The answer is no. Enjoy the Cup.

When I was a child I had what I thought was a brilliant idea: Instead of fighting all those awful wars, countries with gripes should challenge each other to a soccer game. The victor could be declared the winner without all the nastiness of fighting a real war.

My childhood plan for world peace didn’t pan out, but soccer, and the World Cup in particular, remains the premiere arena for make-believe international conflict. It captivates massive crowds, stokes intense rivalries and fills people with surprisingly intense emotions.

This is true even for the people caught in the middle of real wars. In Syria, in the middle of a civil war, rebel fighters put their weapons aside to watch the World Cup. In Baghdad, as the ruthless ISIS jihadists march toward the Iraqi capital, cafes are filled with people watching the Cup.

In Vienna, Iranian officials took a break from nuclear negotiations to watch their team. Refugees, astronauts, politicians are all watching the World Cup.

Clearly, there’s no need for the rest of us to feel guilty. No need for mixed feeling about switching between Obama’s announcement on Iraq and the Colombia-Ivory Coast match.

In Europe, where nationalism got a bad name after World War II, patriotic pride overflows with uncharacteristic fearlessness when the national teams play.

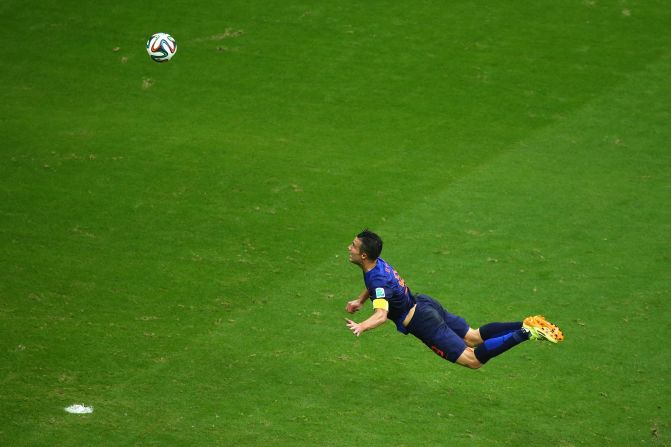

Even people who never pay attention to soccer, known almost everywhere as football, are cheering, bragging about Van Persie’s spectacular diving header against Spain.

The streets of Amsterdam, where I am right now, are filled with the royal colors, with orange streamers, orange flags and toy soccer balls hanging over pedestrian streets and canal boats. When the Netherlands plays, everyone watches.

People love sports, but they love the World Cup for special reasons. Like other competitions, it resembles life in that the outcomes are the product of skill, merit, luck and even unfairness. All the preparation in the world can come to nothing because of a slip in the grass, an unexpected shove, a referee’s mistake. Unlike other tournaments, this one puts countries of all sizes on the stage. Small ones can topple big ones.

It seems as if entire nations take each other on. All the wealth and power in the world cannot protect a squad. The United States is an underdog. China didn’t qualify. England was defeated by tiny, tight-shirted Uruguay.

The tournament distills human emotions to their essence. With so much passion, every point triggers an explosion of unadulterated happiness. What can capture human emotions better than those reaction images from the stands? In Amsterdam, when the team scores, I mute my television and hear the entire city roar with exhilaration.

The tournament may have political resonance, occasionally pitting rival countries, but it also brings out the child in every fan. I have seen grown men walk around wearing neon-bright orange wigs, no doubt wishing they were in the stands in Porto Alegre with their faces painted and Styrofoam cheese for a hat. Everyone’s a child.

Another electrifying aspect of the Cup is that the entire world is watching, even in countries not playing. I have found myself working in a variety of countries during the World Cup, often during times of conflict. For some reason, people everywhere seem to dance in the streets when Brazil wins a match.

National pride is tightly wound with every country’s squad. When a Dutch actress tweeted a Photoshopped picture making it look as if Colombian players were snorting the foam marking kick lines, Colombia protested, and the actress, Nicolette van Dam, lost her post as a UNICEF ambassador. Peace was restored.

The idea that there could be a connection between soccer and peace, as it turns out, came up long before I mentioned it to my father years ago. One of history’s poignant moments came during World War I, in December 1914 – almost exactly 100 years ago – when a Christmas truce was declared and German and British soldiers set their guns aside to play a friendly soccer match. When the truce ended, the killing resumed.

Unfortunately, soccer is no panacea. Even violence directly connected to the Cup occurs.

For most, the World Cup is a wonderful distraction from the difficulties of daily life, from wars and from work, from challenging circumstances and from the knowledge that there is so much else that is serious and troubling in the world.

It is not wrong to watch, much less to enjoy the event, even if it does not prevent or stop any real wars.

Around the globe, the World Cup is a source of sheer excitement, except for the moment when one’s favorite team loses. But here’s the beauty: When your team loses the disappointment is deep, the sadness is real.

Then you remember it’s just a game.

It’s really not the end of the world.

Note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said Russia didn’t qualify for the World Cup.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine