There’s never been an actor quite like Nicolas Cage.

Over the course of four decades, the 57-year-old Oscar winner has done it all, from offbeat comedies (Peggy Sue Got Married, Raising Arizona, Vampire’s Kiss, Moonstruck) and acclaimed dramas (Leaving Las Vegas, Adaptation, Bringing Out the Dead) to action extravaganzas (The Rock, Con Air, Face-Off), superhero spectaculars (Ghost Rider, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse) and gonzo B-movies (Mandy, Color Out of Space). Moreover, he’s done it with a stylized flair that’s marked him as a legitimate original and earned him as many kudos as critiques. In an industry that often prizes conformity and consistency, Cage is the rarest of specimens: a wild-card superstar of outsized personality and inimitable charisma who’s comfortable in almost any genre, even as he remains doggedly true to himself. It’s the key to both his greatness and his enduring appeal.

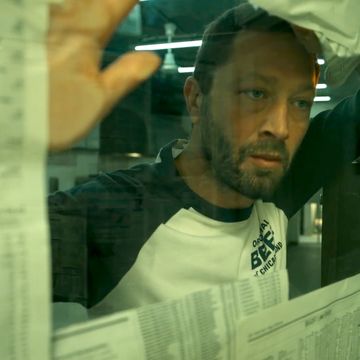

His newest project, Pig, is classic Cage in its envelope-pushing. The feature debut of writer/director Michael Sarnoski, it stars Cage as a reclusive Pacific Northwest truffle hunter who’s compelled, reluctantly, to re-enter Portland civilization (alongside his smarmy buyer, played by Alex Wolff) after his beloved truffle-detecting hog is kidnapped. In a surprising and thoroughly moving twist for anyone expecting John Wick-ian violence, the film proves itself as a somber meditation on loss, grief, the culinary arts and the things that really give life value and meaning. t’s a quiet and heartbreaking film, aching with longing for a measure of joy, companionship, and contentment.

Pig is also a vehicle for one of Cage’s finest turns. As the anguished and driven Rob, Cage locates a wellspring of pain, fear and sorrow that he reveals through small, silent gestures and actions. Gradually exposing Rob’s scarred inner self, Cage transforms the proceedings into a beautifully understated showcase for showing rather than telling, his performance radiating wounded hurt and fury through haunted stares, beaten-down body language, and a weariness that permeates everything he does and says. At once a departure from Cage’s more outlandish recent work and yet imbued with his distinctive energy, it’s a triumph that reconfirms his standing as a peerlessly idiosyncratic artist. Ahead of Pig’s release this Friday,July 16, we spoke with the legendary leading man about all of it: getting back to dramatic basics, his embrace of performative challenges, collaborating with a first-time filmmaker, as well as The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, in which he’ll play the role of his life: himself.

Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Esquire: There’s a scene in Pig in which your character, Rob, explains to a chef that he can’t live life for others because, “We don’t get a lot of things to really care about.” Are the movies still one of those things for you? And is that your philosophy as well – that ultimately, you have to do things for reasons that genuinely matter to you?

Nicolas Cage: The reason I made the movie is because I could relate to Rob. I understood this character, I understood this man. I felt I had the life experience, and the memories, and even the relationship with, for example, my cat, or my dog – who’s no longer with me – that I could tell this story in a way where it was like, no acting, please. It would just come out. For me, when I met with Michael [Sarnoski], the director, I felt we shared similar interests in terms of the tone.

And yes, I was at a point where I was taking…stock isn’t the right word. I was regarding everything I’d experienced, and was really looking for something to portray in cinema with film performance where—you know, Joe is like that for me—here the only thing that was of interest to me was my connection with my relationship with my cat, or what story I wanted to tell, without it being corrupted by any noise that may come from external sources.

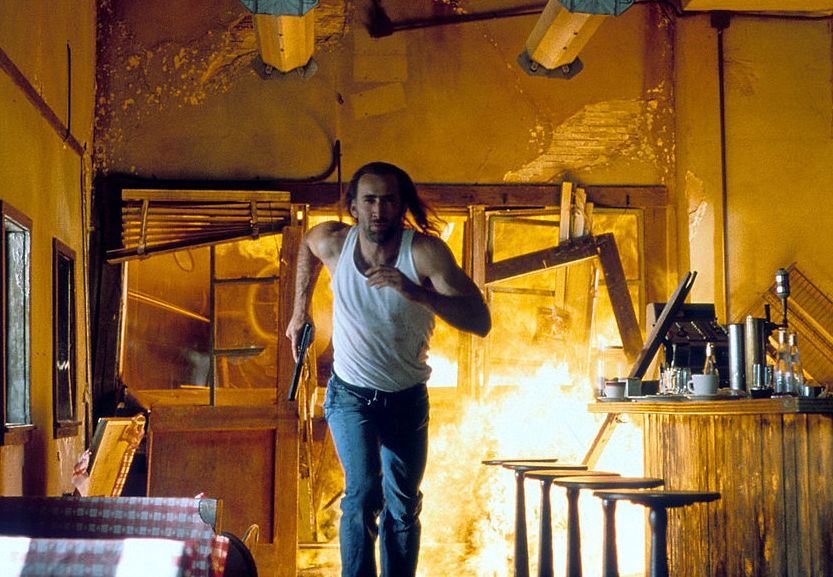

This script was the first thing I’d read in quite a while that really had that. It was like, okay, I can do this, that, and the other I’ve done it and it’s fun and people seem to enjoy that. But that’s not all I can do. I went, very hardcore, at trying to create a kind of operatic “Western kabuki” performance style, if you will, because I was trying to break the form of naturalism.

But somewhere along the way, I think, some folks in the media forgot that I could also do very quiet and internalized performance. That was what I felt I had to get back to. I had to get back to that because, by virtue of that, I can enjoy the Western kabuki even more, but also, reignite my passion for the kinds of movies that I grew up with and motivated me, which were very meditative films about characters like Midnight Cowboy, Ordinary People.

This, for me, was a return to that performance style, and I wanted to get back to that. And frankly, that’s kind of all I want to do now. I really want to focus on the psyche, and drama. That is my passion, and it always has been. So, yes, when it was time to play the scene that you brought up, I thought I could speak to that scene, having been through whatever Rob had been through, which is beautifully not explained. It’s implicit. I think somewhere along the way, Rob lost interest in trying to do what everybody else wanted him to do. That scene, and those words, lent themselves to what I had been feeling myself.

Did your recent career path help you feel a kinship with Rob, given that he’s a celebrated superstar now doing his own personal, rewarding thing in his chosen corner of the world?

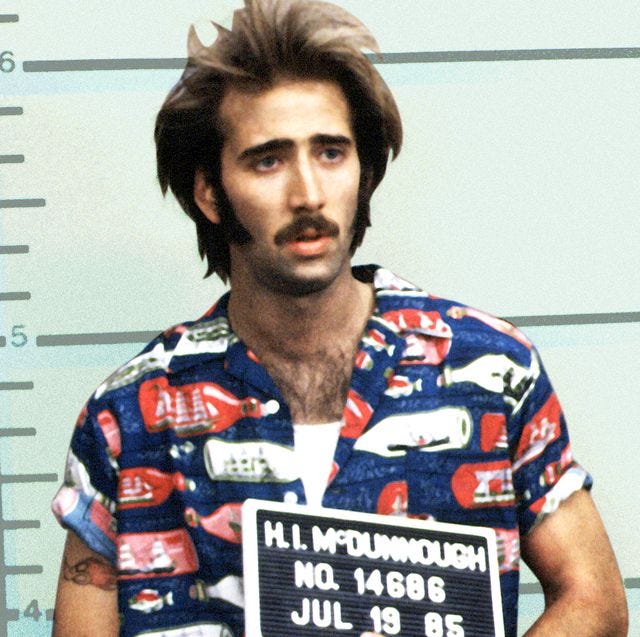

There’s no question that you’re spot on. That’s exactly it. There was a time when I was doing three or four Jerry Bruckheimer movies or whatever, and that was interesting to me because I hadn’t done that. And there seemed to be a question mark in some folks’ minds, in the industry as well as in the media, about whether or not I could even do that. For me, I was always an actor acting like an action hero just to see if I could do it. If I could make a movie with Sean Connery and stay on camera with him. Or if I could play the southern “badass” that I fantasized I could be as a child growing up in Long Beach, California. It was me being a student, to see if I could do it.

I was a fan, and I still am a fan, of the old Charles Bronson movies, and they would come on at night – “The Million Dollar Movie” – and I’d see Clint [Eastwood] or Bronson in these movies, or Dr. No, and I’d think it would be fun to do that. But that wasn’t my first passion. The reason I became an actor is because I saw James Dean in East of Eden, and the effect his nervous breakdown had on me, when he’s trying to give the money to his father and the father doesn’t accept him – that affected me more than anything else. More than any rock song, more than any classical symphony, more than any painting. So my roots, my true passion, was always drama.

Get unlimited access to all Esquire's conversations with legends with Esquire Select.

I had to get back to that, and I felt this movie really gave me an opportunity to explore my first passion in cinema, and to do it in a way where I felt like I was at that moment in my personal life where I didn’t have to act. I wanted it to just resonate without any kind of applied special effects or performance theatrics or anything. This was more about, let’s get back to the microcosm, both internally and externally, and see what that may communicate.

The bare-bones set-up of Pig is reminiscent of John Wick, but it completely subverts any audience expectation for vengeful violence. Did you see the film, at heart, as a love story?

Yes, and I would say that [producer] Vanessa Block, for one, would agree with that sentiment, that it’s a love story with his animal best friend. And it’s also a love story with best friends, given the relationship that evolves with the Amir character [played by Alex Wolff].

I had not seen John Wick, and there was no interest in John Wick. I don’t think there’s even one gunshot in this movie. This was simply a return to quietude and meditation for film performance, and for some reason…not that John Wick isn’t excellent for what it is. I just can’t think of a movie further from John Wick than Pig. And I know the filmmakers never had John Wick on their mind either. There’s just something about the way John Wick landed with the filmgoing audience that made that culture think, let’s connect the dots, there’s a missing pig and a missing dog. But there’s no correlation.

How much did you research truffle hunting? Or was that element of the film largely handled by the script?

The truffle hunting, I didn’t go too far with that. But what I did explore, and take some time with, was working with a couple of the chefs that were Portland-based, and their passion for cooking. Food is very important to me, and I think that comes through as well in the movie. The care and the love for food, not only for sustenance, but also as a spiritual art form. I spent some time with that. As I said, it is important to me, and I appreciated that I had some good teachers, which helped.

Michael Sarnoski is making his feature debut with Pig. Is working with a first-time filmmaker a daunting proposition, or an exciting one – especially on a movie where it seems like there’s a lot of trust required between director and actor?

I had the added benefit of knowing that he wrote the script. Michael and I sat down for lunch, and we had a very quiet and heartfelt conversation about the meaning of the script. How it affected me, and how I would like to play this part. It seemed very easy. Nothing was forced in the storytelling, and I had great faith that we wanted to make the same kind of movie. I often compare it to a cinematic haiku, where the spaces between the syllables are as important and evocative as the syllables themselves. The 5-7-5. Very sparse usage of dialogue, and even sparse usage of shots. What the camera is resting upon, they gel with the performance. That was, I think, something that a lot of thought went into, and was a welcome breath of air for me.

So much of what I had been doing in recent years had been more externalized, and this was a chance to inhale and hold the oxygen in for a bit, and feel, breathe in, breathe out, and let this be slow and meditative and gentle. We shared that passion for this material. So to answer your question, I was not concerned at all about Michael’s vision. None of that, “Oh, he’s a first-time director” crap came into my mind. It was, he wrote this beautiful script that almost feels like a haiku, and we’re going to make a movie that we’re both going to enjoy.

Is that almost more challenging – to hold the oxygen in, so to speak, versus giving a more externalized type of performance?

No – it was a welcome relief. It was a return to a different kind of performance style that I was craving. That’s not to denigrate the Western kabuki stuff I’d been doing, which was also by design, because I was interested in challenging film performance as a style that wasn't just naturalism. But I felt it was time to remind some folks in the audience, as well as myself, that I can also paint with this brush.

Not that I’m Picasso; I’m not. But I remember asking my father if Picasso – because he did these marvelously bizarre, surrealistic, abstract portraits, with eyes on the side of the face – could also paint photorealistically. And my father was like, oh yeah, he broke form. So I was like, okay, I want to try and see – because I believe in art synthesis – if there’s a way to do that with film performance. And I explored that. But it was time to get back to the quiet, photorealistic portraiture. I needed to do that for myself, and I think some folks in the media needed to be reminded that I could do that. So the timing of it was right.

Next on your plate is The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, in which you’re playing a version of yourself. How does that project fit into your desire to return to a more interior performance mode?

I think The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent is, again, a challenge. I’m of the mind that if there’s something you’re afraid of, chances are it’s the very thing, within reason, that you should face. That one should go towards it, as long as it doesn’t hurt yourself or anybody else. If you fear it, maybe there’s something there that you need to approach. It’s kind of the way I feel about maybe going on the boards, with stage, but I don’t know that yet. I don’t know what I’m going to do with that.

Massive Talent scared the crap out of me. I was like, what is this going to be? This is [writer/director] Tom Gormican and [writer] Kevin Etten’s surrealistic and abstract interpretation of a version of me, and a younger version of me, combatting one another. I can tell you that I know everybody who made that movie went in with complete enthusiasm and care, and there was nothing schmaltzy about it. They genuinely cared about the project, and they took their time with it, and it took a piece of my soul to do it. And I will never see the movie, because it’s too much for me to process on my psyche – that I’m looking at two abstract interpretations of myself, because in my own life, I don’t have a daughter, so there are very few similarities.

I’m told the movie is good, and it’s going to be a lot of fun and people are really going to enjoy the ride. I’m just not going to be in the audience; it’s too hard on my psyche [laughs]. I don’t want to think about that, psychologically. I just don’t want to do it! I’ll go to the premiere, but I will not sit in the audience. I will wait, and I will listen.