“For me, photography can be dead serious or great fun. Trying to capture the elusive truth with a camera is often a frustrating toil. Trying to create an image that does not exist, except in one’s imagination, is often an elating game.”

Philippe Halsman used the equivocal nature of photography to play with reality as well as with the imagination. The American photographer, who began his work in Paris in the 1930s and continued in New York City in the 1940s onward, is remarkable for the wide breadth of his work:.

The Jeu de Paume exhibition in Paris honors and showcases his portraits, his works in fashion, reportage as well as his advertising photography. They all have one trait in common: photography is used as a joyful, creative, surprising medium, whatever the lens focuses on. The success of the show, titled “Astonish Me,” can be found throughout the gallery. Walking around, one sees how the images trigger an unusual reaction among the viewers: you see them smile and pull a friend’s sleeve to show a tiny detail; sometimes you even hear them burst into laughter. The gallery is transformed into a sort of playground, which echoes Halsman’s own views on photography.

First and foremost, Philippe Halsman remains famous for his portraits of celebrities, and for breaking the record with the publication of 101 Life magazine covers. But the exhibition, by bringing together (for the first time) many contact sheets, preliminary proofs and original photomontages, also gives us behind-the-scenes insight into the range of Halsman’s work. Surprisingly, portraits of homeless people are displayed next to photographs advertising luxury jewelry for Vogue. Glamorous portraits of actresses and dancers are side-by-side with cheeky self-portraits. These juxtapositions would probably have made sense for Halsman—after all, his main goal was not to document but to explore the possibilities of the photographic medium.

Halsman published many of his celebrity portraits in influential magazines, such as Life, TV Guide, and The Saturday Evening Post. He was obsessed with capturing people’s genuine personality, even when they posed. He gradually invented new stratagems. His first famous portrait of the French writer André Gide in 1934 is quite conventional: Gide is looking down, wearing his highbrow glasses and austere clothes. Albert Einstein’s pale face, on the other hand, is a turning point. In this deeply moving image, the scientist looks straight at the viewer, his hair is dishevelled and his collar not adjusted. Legend says he had just told Halsman about his guilt of being one of the fathers of the atomic bomb.

Looking for a new approach to the psychological portrait, Halsman even invented his own kind of science in the 1950s: he called it “jumpology.” By asking his subjects to jump in front of his camera, he made them uninhibited as they concentrated on their jump, “allowing the mask to fall.” Halsman managed to convince many different celebrities to partake. He ended up taking more than 170 jumping portraits, later published in The Jump Book. A whole room of the exhibition is dedicated to this motif, creating a surrealistic space, a surprising family of portraits capable of gathering the Manhattan Project scientist-in-chief Robert Oppenheimer, with the politician Richard Nixon and the actress Marilyn Monroe (it took them three hours and more than 200 jumps to obtain the iconic Life magazine cover picture). Even the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, after carefully taking their shoes off, agreed to jump in a very elegant yet stiff posture.

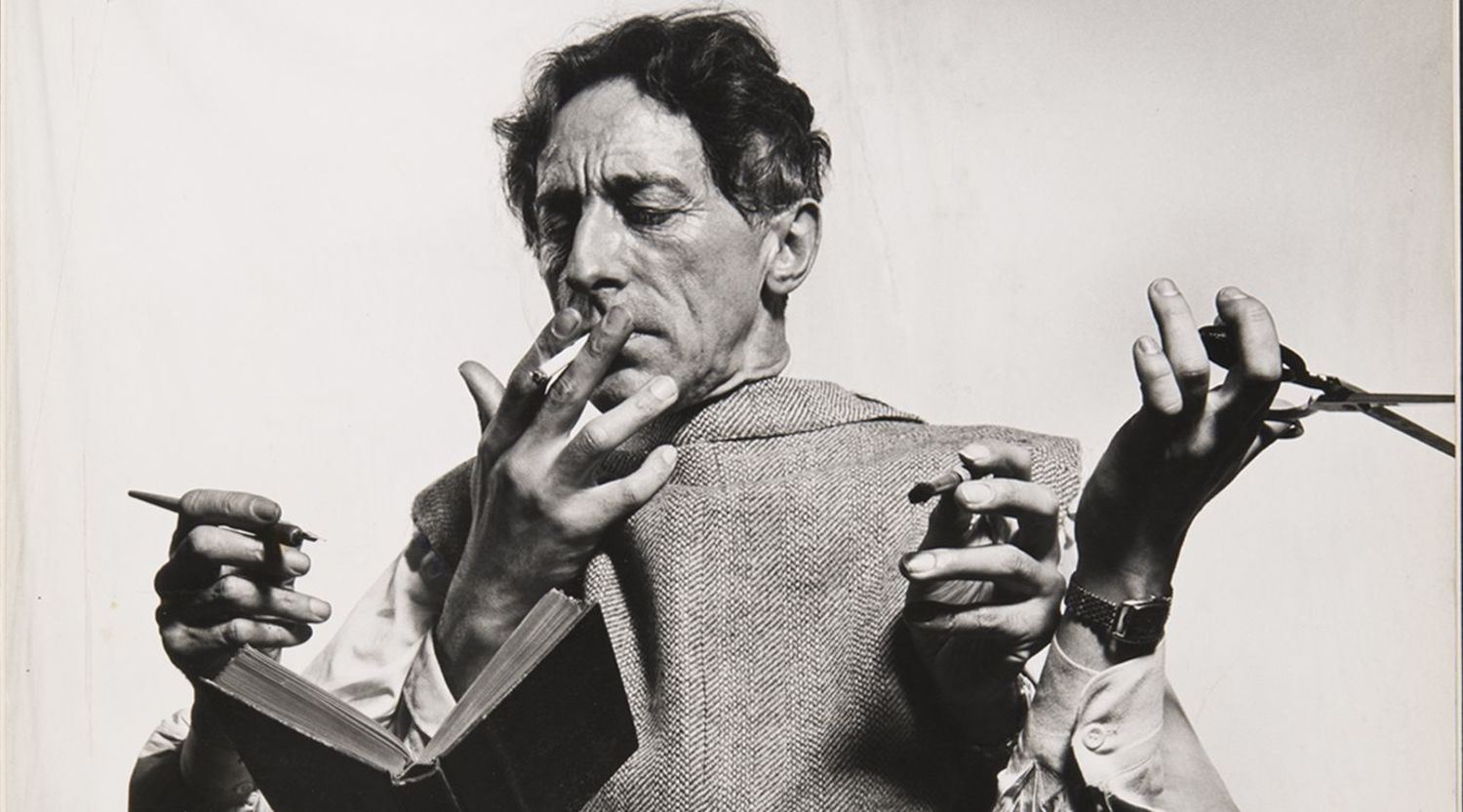

Concurrent with this method, Halsman started using photomontage in a very creative manner. A bird is perched on Hitchcock’s pipe while he smokes; Warhol’s face is painted in flashy colors, reminding us of his own techniques. Jean Cocteau, “the Versatile” artist, has no fewer than six hands, while the photographer Eisenstaedt has three legs. These visual aberrations make use of the idea that a staged or even retouched photograph can be more true to its subject than “straight” photography.

The playground expands in particularly fruitful directions when it comes to working with the Spanish artist Salvador Dali. Their long collaboration in the 1950s seemed to be mostly about having fun, as they shared a schoolboy sense of humour, a biting sense of irony and a strong fascination for Surrealism. It led them to publish a whole photomontage book featuring Dali’s mustache, and to restyle masterpieces such as Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. In “Dali Atomicus” (1948), they even tried to stop time: Dali is jumping, a chair and a canvas are floating in the air, cats and water are flying. The contact prints let us discover the making-of this fantastic image (and the countless failed attempts): water splashing Dali instead of the cat, the secretary getting into the picture, the timing being all off. These little discoveries touch the viewer’s interest as much as the final result.

This exhibition is not only a temporary playground in the center of Paris, where the viewer can have as much fun as the photographer; it is also a place where the amateur can get some inspiration. With digital photography and the democratization of cameras, non-professional photographers can easily play with Halsman’s techniques. Actually, they already do: every day on social media, we see tons of jumping pictures, endless restyled famous paintings and fake mustaches placed on celebrities’ portraits. Now in the playful atmosphere of the Jeu de Paume, both experts and curious viewers can explore the origins of these popular practices and imagine what joys are next in the field of photography.

—Laure Andrillon

Editors’ Note: ”Astonish Me” showed at the Jeu de Paume in Paris until January 24, 2016.