- HBO’s Watchmen premieres Sunday night.

- The series is a continuation of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’mega-hit graphic novel of the same name.

- Here’s everything you need to know about the literary touchstone before you tune in.

This Sunday, HBO debuts its next face-stomping antihero extravaganza in Damon Lindelof’s Watchmen, the TV spinoff of the classic graphic novel. Set almost three decades after the novel (which unfolds over two weeks in October 1985), HBO’s Watchmen spins forward the consequences of the comic, following several new and a few leftover characters from the original story. (So yeah, those leftovers are all pretty old by now.)

In a way, the comic acts as the historic spine of the HBO spin-off. Which is a good thing. Because it means the writers respect their source material; they want to do justice to the universe.

And while you won’t necessarily need to read the comic in order to dive into HBO’s TV version, knowledge of the graphic novel will no doubt enhance viewing experience; the series is absolutely stuffed with Easter eggs and literary references—to the point of it almost being obnoxious. Comic awareness will also help you anticipate plot lines and character twists before all your other friends. And just make you seem generally smart and well-read and all that cocktail-party-bragging shit. (Or it’ll just make you seem like a giant nerd. But that’s fine. We’re literary nerds here, too).

So here is everything (and we mean way more than you probably really need to know) about the comic. (We refer to it as a “novel” … because your book-biased English teachers were all wrong; comics are literature.)

How did the original Watchmen begin?

Apparently, it all began with Bob Dylan. So says Dave Gibbons, the artist behind writer Alan Moore’s mega-selling cultural phenomenon, Watchmen. “For me, a couplet from his masterpiece 'Desolation Row' was the spark that would one day ignite Watchmen,” Gibbons writes in the introduction to the 2014 edition of the work. “At midnight all the agents and the superhuman crew / Come out and round up everyone that knows more than they do. It was a glimpse, a mere fragment of something; something ominous, paranoid and threatening.”

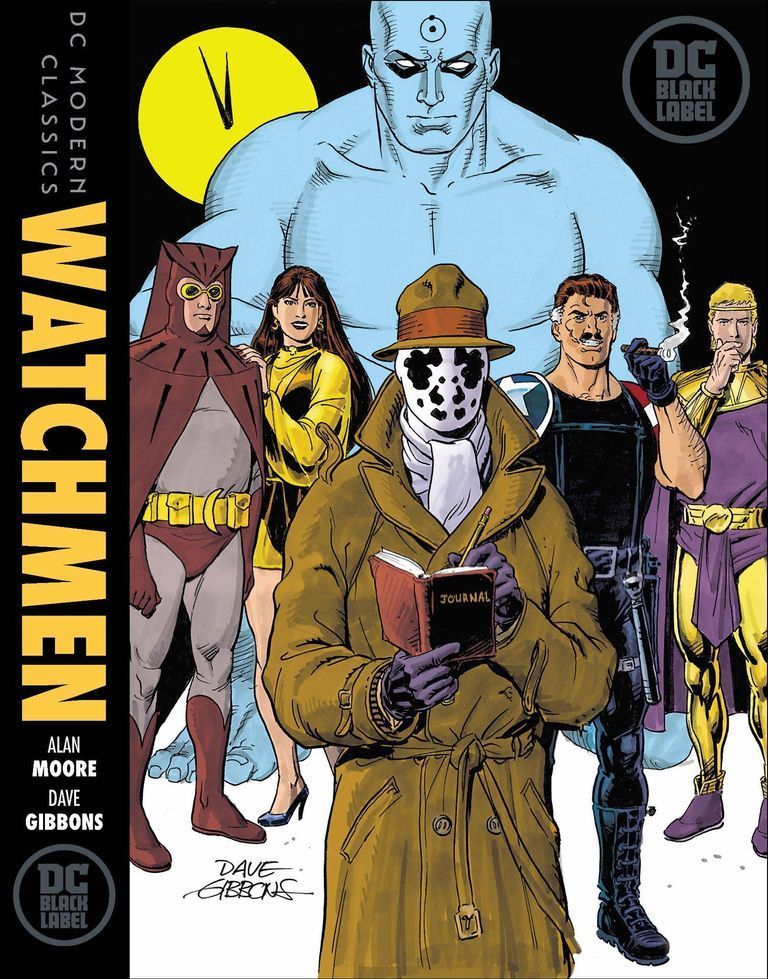

Paranoid and threatening, Watchmen first hit shelves in 1986 as a twelve-issue “maxiseries” (a comic with a set number of installments). After the twelve were released, publisher DC Comics bound the series into a single work, marketing the collection as a “graphic novel” in order to disassociate it from traditional serialized comics.

While Watchmen wasn't the first of the graphic novel form, it did make the stridently bloody argument for the comic as a serious artistic and literary medium. (Moore has even indirectly compared the work to Moby Dick.) And Watchmen should be counted beside opuses from authors like Thomas Pynchon, Don DeLillo, and Cormac McCarthy in the canon of post-war American literature. (It frequently and deservedly appears on lists for the best English language works of the last century.)

Who are the creators?

Watchmen was written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Dave Gibbons. Moore may, in fact, be the most famous comic writer in recent history. His other massive film-adapted works include The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and V for Vendetta.

Who are the “Watchmen” described in the title?

A better question is Who watches the Watchmen?

After the first masked vigilante appears in the story's fictional 1938, a collection of other caped figures band together to form “the minutemen,” Moore’s campy-high-tights ode to early superhero comics. The minutemen disband in 1949 after “there was nobody interesting left to fight” (the heroes’ equally-campy villains had since been imprisoned) and after several masked heroes are killed—one for being gay.

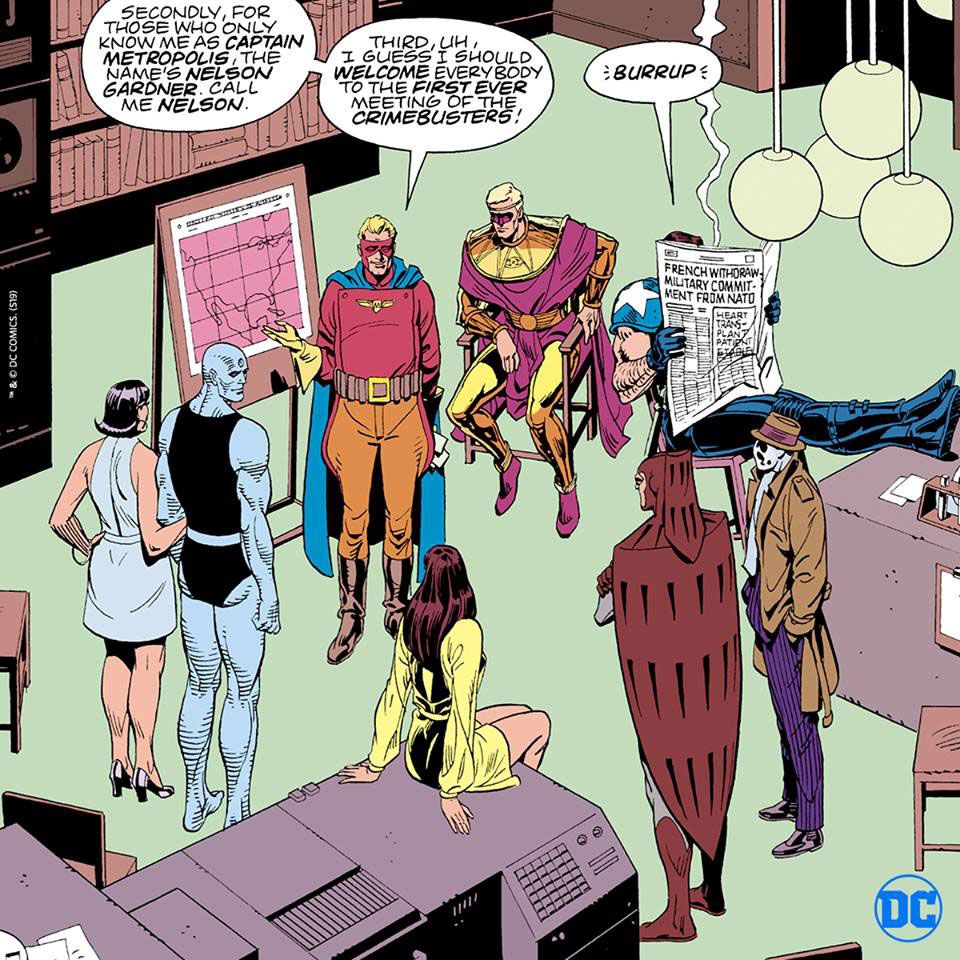

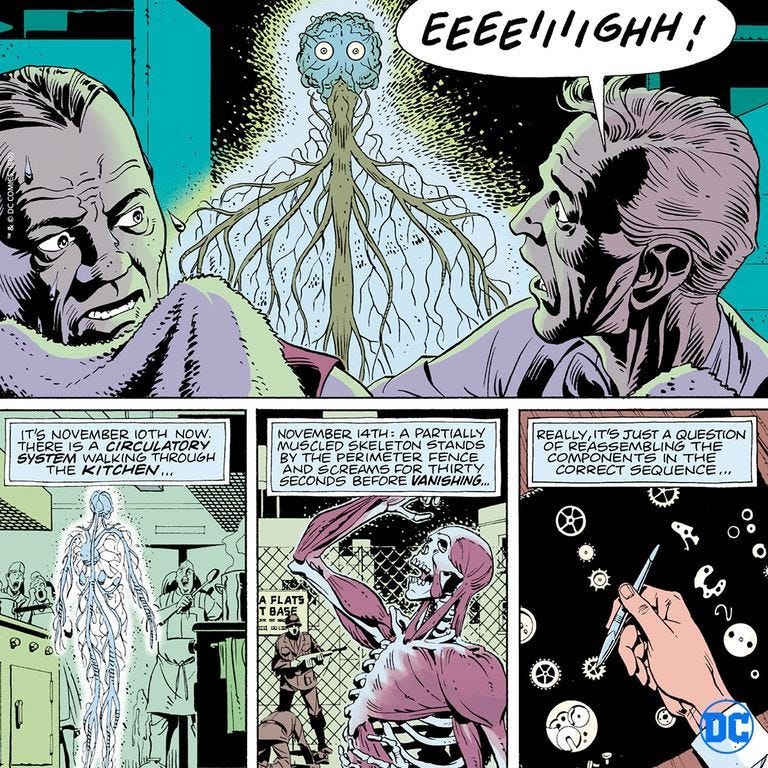

In 1960, a new breed of superhero emerges with the “birth” of Dr. Manhattan, an atomic physicist who is vaporized in a lab generator and then slowly and spontaneously regenerated as an all-powerful blue demigod over the coming months. (His brain, eyeballs, and circulatory system materialize first). Dr. Manhattan becomes the novel’s most traditional superpowered hero, and his existence threatens to render heroes obsolete. He and several other characters, including fellow heroes Ozymandias, Nite Owl, and Rorschach attempt to form a group called the “Crimebusters.” The experiment fails before it can begin. Former minuteman The Comedian disbands the meeting, proclaiming that the superhero endeavor “don’t matter squat because inside thirty years the nukes are gonna be flying like maybugs.” Still, the group continues to fight crime. Some like The Comedian and Dr. Manhattan join the U.S. military’s efforts in the war in Vietnam.

In 1977, a congressional act bans superheroes and all vigilantes disband. Many retire to careers in science and business.

The name “Watchmen” is never used in the comic. The moniker comes from Roman author Juvenal’s “Satire VI,” which contains the phrase “sed quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” — “But who will guard the guards?” or “But who will watch the watchmen?” One of the novel’s many themes concerns constraint on power. The fictional congressional act banning superheroes attempts to exercise this control. That plan fails miserably.

Where/when does the story take place?

The story primarily takes place in 1985, but will flit in and out of varying years between then and 1960, the so-called “dawn of the Super-Hero” when Dr. Manhattan is announced to the world. “The superman exists,” proclaim the TV reporters, in the novel's most famous line, “and he is American.” 1960 also marks the year in which the novel’s world and the world outside the pages diverge.

Once Dr. Manhattan allies with the American government, Cold War power imbalances quickly shift. Dr. Manhattan intervenes in the Vietnam War, which then ends with an American victory and the Vietcong bowing before the doctor as though he were a god. Dr. Manhattan then uses his powers to generate a battery for motor vehicles, creating electric cars, bolstering the U.S. economy, and further outpacing the Soviets. The 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan occurs as it did in the non-fictional world — though, here the Russian occupation occurs several years later and only after Dr. Manhattan flees earth (and no longer acts as a deterrent). This time, the Afghanistan campaign expands into neighboring Pakistan, threatening a nuclear exchange and World War III.

What is Watchmen about?

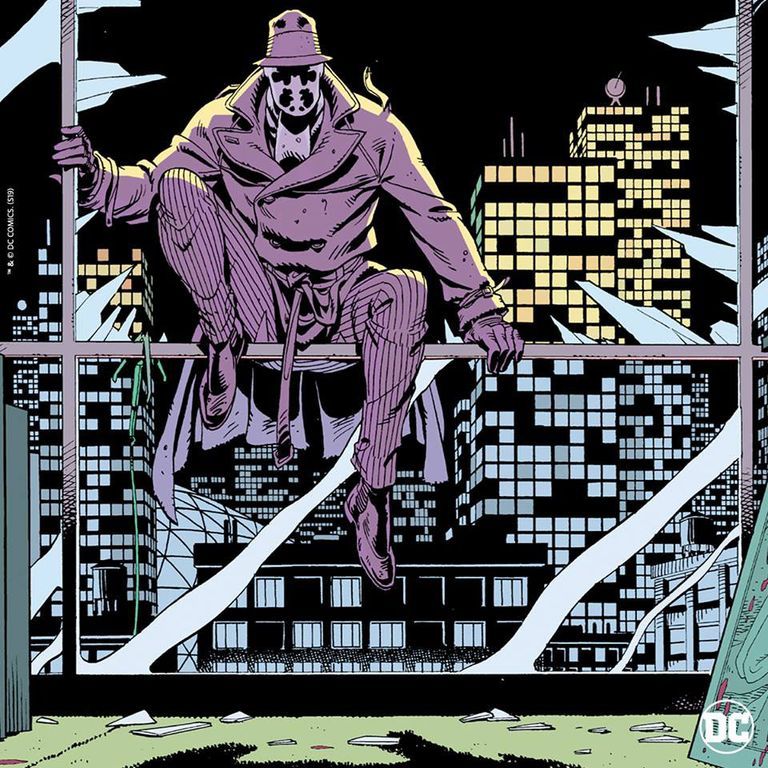

The major events of the Watchmen novel begin on October 12, 1985. The date marks the first entry in Rorschach’s journal, the basic framing device for the novel. Rorschach investigates the death of The Comedian, whose blood is shown being hosed into a sewer drain in the seven panels of the novel’s second page. (The opening page depicts an even closer image of the blood, here staining a yellow-and-black smiley face button once worn by The Comedian).

Rorschach, believing someone to be killing masked heroes, warns the other (former) heroes: Dr. Manhattan (who dismisses his concern), Silk Spectre (a minuteman daughter and girlfriend of Dr. Manhattan; she storms off in the face of Dr. Manhattan’s apathy), Nite Owl (who slowly adopts Rorschach’s paranoia), and Ozymandias (now a successful businessman who responds to the news calmly).

The Nova Express (an anti-superhero newspaper) then publishes a story holding Dr. Manahattan responsible for his past lover's cancer. Frustration and growing-apathy leads Dr. Manhattan to leave earth for Mars. Soviet-U.S. nuclear tension increases in his absence.

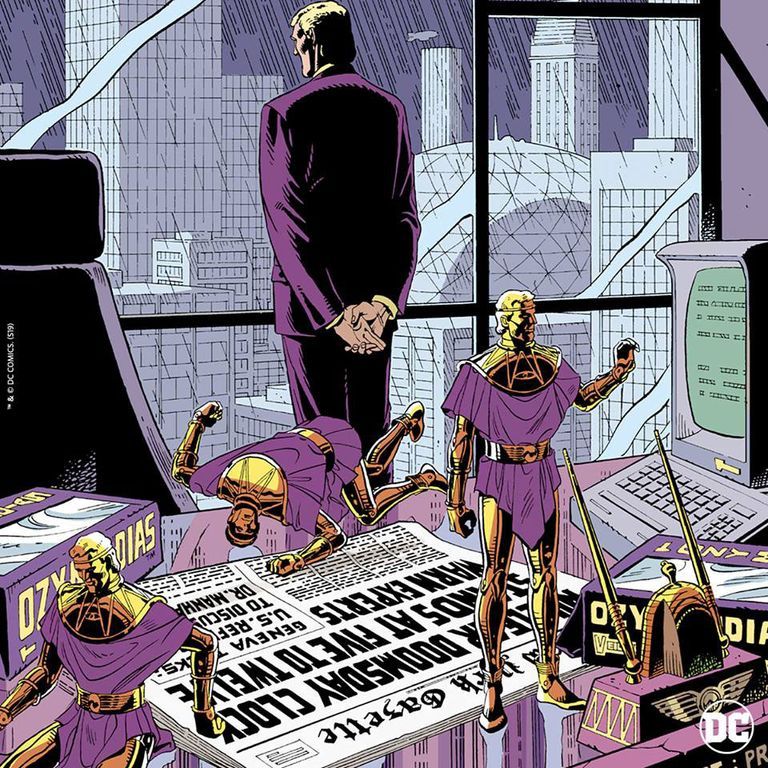

Rorschach is framed and then arrested. Nite Owl and Silk Spectre break him out. Silk Specter is transported to Mars to speak with Dr. Manhattan, while the other two journey to the arctic to find Ozymandias, after evidence of vigilante killings begin pointing his way. In his lair and surrounded by news monitors, Ozymandias reveals that in an attempt to avoid nuclear holocaust, he has engineered a plan to unite the world’s superpowers. The plan involves teleporting a genetically-engineered monster into New York City, an event that will kill half the city’s population and convince both superpowers to unite in opposition to this new extraterrestrial threat. After he’s finished talking, he reveals the event has already occurred and millions of New Yorkers are dead.

Ozymandias’ plan, however, appears to succeed, and all the heroes decide to remain quiet. All except Rorschach who refuses to keep the secret. Dr. Manhattan then obliterates him.

The novel concludes with reporters from the pro-vigilante paper the New Frontiersman

digging up Rorschach’s diary from out of the slush pile — the opening lines of which begin the novel — and so brings the narrative full circle, into a kind of never-ending ouroboros

loop: "Dog carcass in alley this morning, tire tread on burst stomach. This city is afraid of me. I have seen its true face."

Also worth noting

Throughout the novel, an unnamed character can be found reading a comic book beside a newsstand. This comic within the comic, titled “Tales of the Black Freighter” has no impact on the story aside from its thematic connection to Ozymandias—both he and the comic’s protagonist must live with their having killed innocence.

In HBO’s Watchmen trailer, a pirate flag with the freighter’s emblem can be seen, suggesting that the comic may somehow have inspired some kind of real-world faction.

What is Watchmen really about?

Of course, Watchmen is not simply about a collection of misbehaving caped crusaders (at best) or degenerate vigilantes (at somewhat worst). Moore also uses the story as a means to (1) reflect on contemporary anxieties and (2) deconstruct and satirize the superhero concept.

When Moore wrote the novel, the country was still reeling from Watergate and the military failures of Vietnam; there had been a breakdown of public trust and little appeasement to the growing fears of nuclear exchange. In these concerns, Moore positions himself beside many writers of his time, and his novel’s central themes include many of the same which appear across so-called “postmodern” literature: paranoia, distrust of science/technology, the farce of government and institutions of power, and the unreliability of information — its fabrication by those of authority and its manipulation by those purporting to “watch” authority: the media. (If these themes of dysfunctional power and the distrust of media feel familiar, perhaps now really is the perfect time for a Watchmen sequel.)

Like its literary counterparts, Watchmen responds to all these concerns with irony. The Comedian, so named because of his sardonic attitude (he accepts the coming nuclear war and turns the streets into a kind of amoral playground), is held in strangely high regard by the novel’s epistolary narrator. As Rorschach puts it: “He saw the true face of the 20th century and chose to become a reflection, a parody of it.” The description is also Watchmen’s: a reflection of late Cold War America, a parody of it.

It’s hyper realism also parodies superhero literature—everything from its costume campiness to it’s absurd motifs (villains monologuing battle plans, supermen saving the day from existential threats, etc).

Did Watchmen have a sequel?

It did. It does. The Doomsday Clock comic series follows the events of Watchmen. This series may be the closest chronological link to HBO’s upcoming series, which takes place well after the destruction of Manhattan. (Ozymandias, played by Jeremy Irons, is now an old man). Still, we only know so much about the series so far.

The Doomsday comic, however, takes place only several years in the future. Following Ozymandias’ false flag operation, Rorschach’s journal is published by the press. World chaos ensues. Ozymandias becomes a fugitive and begins seeking out Dr. Manhattan to help save the world. At this point, there’s a lot of crazy universe jumping that combines DC’s Superman universe with that of the Watchmen. Dr. Manhattan meets the Flash. A Rorshach successor comes along for the ride. (It's all very weird.)

Doomsday Clock lacks the narrative and artistic ingenuity that made the original graphic novel so captivating, but it’s the closest thing chronologically to the new HBO series. So maybe worth a read.