In the years before Padma Parvati Lakshmi Vaidyanathan, the daughter of an immigrant nurse from Chennai, India, became Padma Lakshmi, the glamorous and unflappable Top Chef host who tells cook-contestants to please pack their knives and go, she was an actress trying to make a career in Los Angeles. Her only respite during those days of casting calls, auditions and many rejections were the dinner parties she threw, where fellow industry stragglers would gather in her apartment to snack on coconut chicken and chickpea tapas. Word of the "model who ate and cooked"—and the legendary dinner parties she threw—reached Miramax studio head Harvey Weinstein, and soon Lakshmi's acting aspirations gave way to an entirely different career, as a TV personality.

Lakshmi is neither a nutritionist nor a trained chef, but over the past 13 years—as the author of cookbooks and the straight-faced but warm host of Bravo's Top Chef—she's garnered enough culinary cred that when she tells you the proportion of shrimp to put in your paella, you're inclined to listen. Her love of food and her savvy hustling helped her create a meaningful career in the crowded celebrity-chef industry.

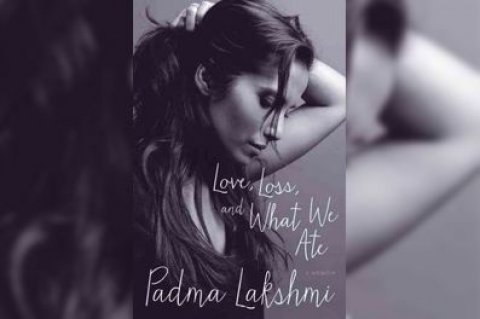

The "why" of Lakshmi's success isn't hard to decipher: She's beautiful, smart and a serious multitasker. But the questions of how—how her career actually came about, how she survived becoming a gossip column target, how she parlayed a love of food into a culinary career—have always been hard to answer. In her new memoir, Love, Loss, and What We Ate, Lakshmi finally gets candid about her unorthodox life—her upbringing in Chennai, a car accident at 14 that left a 7-inch scar on her arm, a debilitating bout with endometriosis and her exhausting marriage to novelist Salman Rushdie—while revisiting the dishes that helped her establish a place in the industry and get through dark times.

A confessional tell-all was not the book she originally set out to write. After nearly two decades, Lakshmi says, she'd had enough of trying to come up with pithy sound bites about how she "stayed so thin" despite her culinary-adjacent career. "It actually started out as a book on healthy living and healthy eating, using the details of my own life to illustrate certain philosophies that I had about food," Lakshmi tells Newsweek at her Manhattan apartment on a warm March afternoon. "And I thought, Rather than just sit and pontificate because I'm on TV, give real-life examples."

She began to look back at what different dishes had meant to her during the most trying times of her life, especially the ones that unfolded in the public eye. "I just kept going further and further into the personal stories I was excavating," she says of her book. "I wound up writing about something much deeper, about something that feeds me."

Sometimes that means the things that actually fed her. There are recipes at the end of each chapter, personal ones like the chili cheese toast of her childhood, the kumquat chutney she made in bulk after her marriage to Rushdie disintegrated, the egg-in-a-hole she ate just before going into labor. It's inconsistent as a cookbook, but the dishes should be read more as a refrain for the memoir's theme: It's not lost on Lakshmi that she has food to thank for her success.

It's not her first foray into writing. Lakshmi's literary career began in 2001, when Vogue editrix Anna Wintour asked her to write about the story behind her scar. After that, a chance remark to an editor about being raised by a feminist mother led to a series of columns for Harper's Bazaar and a syndicated column for The New York Times. She published her first book in 1999—Easy Exotic: A Model's Low-Fat Recipes From Around the World—which was, true to its (somewhat Orientalist-baiting) title, a collection of simple-enough recipes drawn from Lakshmi's experiences as a model shuttling between Italy, New York and Los Angeles.

Since then, she's published another cookbook, hosted 13 seasons of Top Chef (for which she's earned an Emmy nomination), guest-starred on 30 Rock and been on the cover of Vogue India. Which raises an uncomfortable question: Does a woman so visible, so often in the tabs, really need a memoir? "If I'm being perfectly honest, I wanted to be considered a serious writer," she says of her reason for doing this book. "I don't want to be considered the pretty woman on TV who tells you how she stays thin."

And the book gets serious in a hurry, addressing her long-speculated-about marriage to the Booker Prize-winning Rushdie on the first page. The celebrated, middle-aged intellectual smitten with a much-younger model (with a cookbook to her name) launched a thousand salivating tabloid headlines over the eight years they were together—most of which lashed her. One newspaper blared that "something about Padma Lakshmi makes it hard to take her seriously." Another published her (incorrect) bra size. ("They could've just looked up my measurements on my agency's website," she deadpans.) A New York Times profile anointed her a "semi-celebrated hustler." Their split was replete with all the usual he-said-she-said recriminations, but theirs were published copiously in the New York Post.

Lakshmi says years of perspective have siphoned away any bitterness over that relationship. She speaks respectfully of Rushdie, though there is one droll gibe in her description of their first meet ing in her new book. An obviously smitten Rushdie attempted to engage her in conversation with a groan-worthy opening line, declaring his interest in "diaspora stories," how much hers had fascinated him and would she perhaps be interested in telling him more.

She wondered if he wasn't some distant uncle. "I sincerely thought, This must be a family friend. Because there's no way Salman Rushdie could know that much about my life."

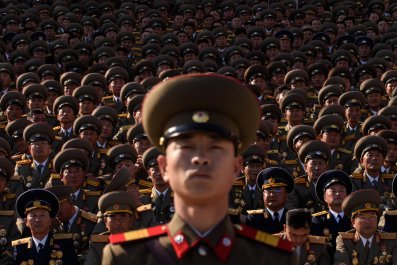

Lakshmi's new book has plenty of anecdotes from their eight-year relationship, recalling the good times as well as the strange pitfalls of being married to a highly celebrated novelist. She remembers rolling her eyes when Rushdie declared himself "Nobelisable" after losing out on the Nobel Prize for a second time. Another time, they argued over the merits of his Newsweek cover versus hers. "That's great, I'm happy for you" was Rushdie's chilly response when Lakshmi got her own cover, she writes. "The only time Newsweek put me on their cover was when someone was trying to put a bullet in my head," he said, a reference to the 1989 death fatwa ordered by Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini over the publication of Rushdie's novel The Satanic Verses.

Lakshmi writes that, even as a well-read and well-traveled woman, she often felt out of place and intimidated in Rushdie's social circles. But o nce she'd gotten past being starstruck and lovestruck, she became less inclined to play the role of his rapt audience. "Both of us tried our best. Whatever Salman's faults, he did love me," she says. "We failed each other, but I couldn't fail myself."

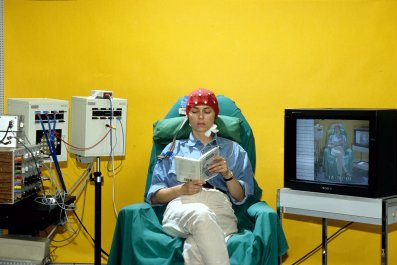

She says it was his insensitivity regarding the pain caused by her endometriosis that convinced her they had to split. She'd learned to live with extreme chronic pain all her life, suffering from bloating and lower back pain so intense it would incapacitate her for days and leave her unable to book modeling jobs or even move. Endless visits to the doctor ended in misdiagnoses that did nothing to abate the pain. Sex became an extremely painful ordeal, and that led to further frustration in an already tense marriage. Finally, at 36, she was diagnosed with endometriosis, a condition where tissue similar to the uterine lining, instead of being expelled from the body, piles up and is re-absorbed back into the uterus, attaching itself to other internal organs and preventing them from functioning normally.

According to the National Institutes of Health, at least 5 million women in the United States have endometriosis, yet it remains woefully underdiagnosed. Studies show that the period from when the symptoms start showing to the final diagnosis takes anywhere from six to 10 years.

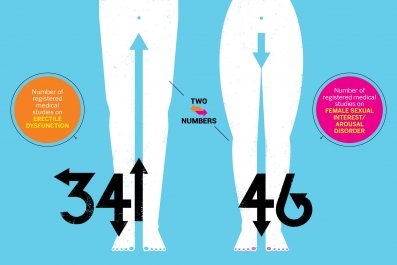

In Lakshmi's case, it took 23 years of being sent home with medicines that did nothing and dealing with doctors who cut away at her reproductive system to no avail. A conversation with a fellow patient, a teenager, led her to finally realize that if anyone was going to speak up about it, it would have to be her. "If I had erectile dysfunction or a prostate problem," she says, echoing an argument used frequently by women's health advocates, "there would be 14 drugs and all sorts of research available!"

With the help of Dr. Tamer Seckin, the doctor who correctly diagnosed and treated her, she founded the Endometriosis Foundation of America. Since then, she has become a vocal crusader, speaking up about her illness before senators and students. "I was conditioned to think I have to suck it up and that it's my lot in life," she says. "It's not."

Two days after her conversation with Newsweek, she attended a briefing in Washington, D.C., to talk to a roomful of senators, where she opened with the line "I'm going to be talking about my vagina, but you'll make it out of here—it will be OK."

With the release of Love, Loss, and What We Ate, Lakshmi's takeover of the headlines begins once again. Stories will probably be written to test if her book's recipe for "cranberry drano" really helps keep that Top Chef weight off, and tabloids will titter over that time Rushdie called her a "bad investment."

But this time, she won't have to depend on those headlines to tell her story. And for those who want to know about Padma Lakshmi—the immigrant living in a cramped studio apartment with her mother, the teenager who named herself Angelique to hide her ethnicity in high school, the actress who was once too brown and too past her prime to land a Hollywood agent—they can get the dish directly from her.