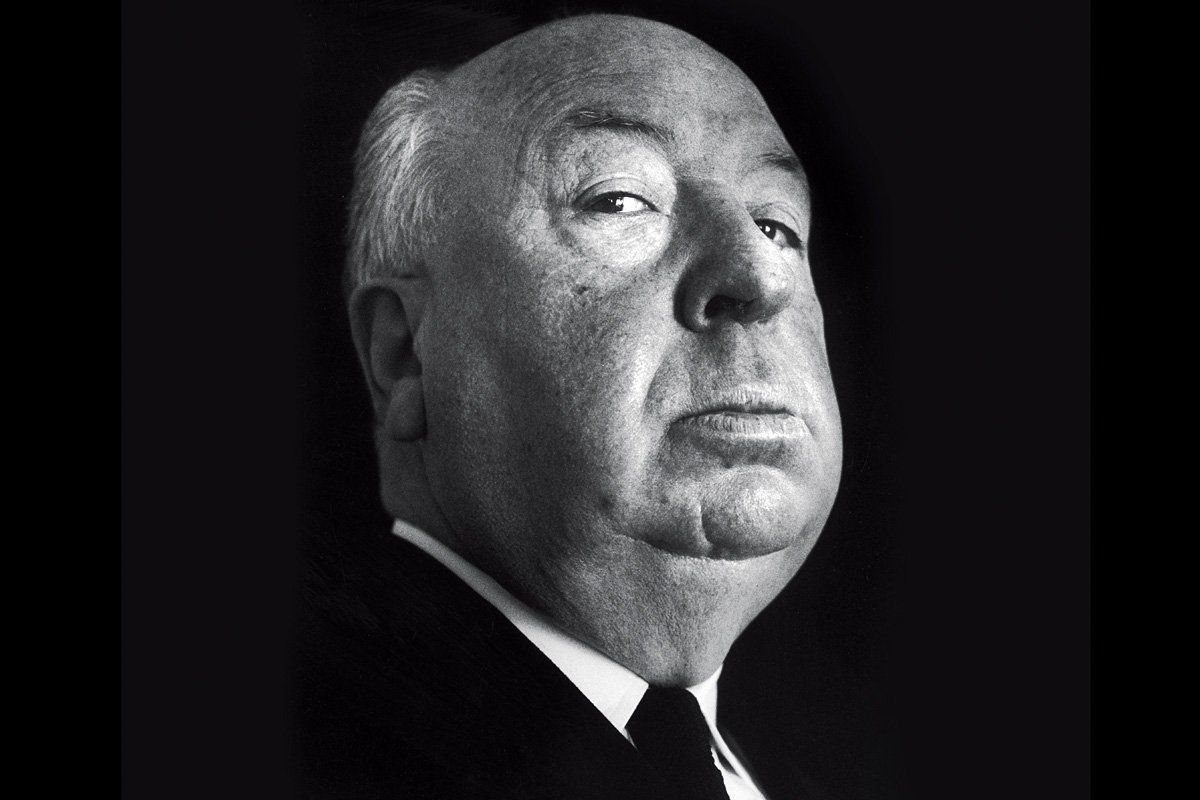

To say he's making a comeback would be misleading, because he never went away. Alfred Hitchcock's place in the pantheon of great directors has long been secure, thanks to a string of classics stretching from the 1930s, when he created gems like The 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes, to the films that conquered Holly-wood in subsequent decades, including Notorious ( 1946 ), Rear Window ( 1954 ), and The Birds ( 1963 ). Stylish, literate, beautifully constructed, visually opulent, they showcased the period's most fetching stars (including Ingrid Bergman, Grace Kelly, Cary Grant, and James Stewart). No popular film-maker has been more admired by critics in his own lifetime.

Now something new is going on with Hitchcock. Thirty-two years after his death, he has become more relevant than ever, the subject of fresh and contentious speculation, his reputation as a director soaring to new heights even as a campaign seems underway to expose him as a bully and beast.

The British Film Institute, in its largest-ever undertaking, has been diligently restoring eight of the nine films Hitchcock made in the silent-film era, when he was in his 20s. This past August, 846 critics and professionals from the film industry voted Hitchcock's Vertigo the greatest film of all time, toppling Citizen Kane from its 50-year-long perch, in the prestigious Sight and Sound poll (conducted once a decade). But good news was followed by bad: in October, The Girl, a 90-minute HBO biopic, depicted Hitchcock (Toby Young) as a sexual harasser who destroyed the career of a fresh-faced Tippi Hedren (Sienna Miller) after she refused to submit to his demand that she make herself "sexually available" to him when the two paired up to make The Birds.

Perfection of the work vs. perfection of the life is an age-old conflict, but in Hitchcock's case the dichotomy resists convenient parsing, because the facts of his life are so tightly raveled with the big themes in his work: the thwarted desire that darkens into monomania, the tense duality of inhibition and violence, the exalted vision twinned with the near-sadistic drive for total control, especially over the actors he said "should be treated like cattle." These warring impulses shaped Hitchcock's ceaseless striving "to manipulate an audience's sensibilities to the utmost," as Donald Spoto wrote in The Dark Side of Genius, his biography of the director.

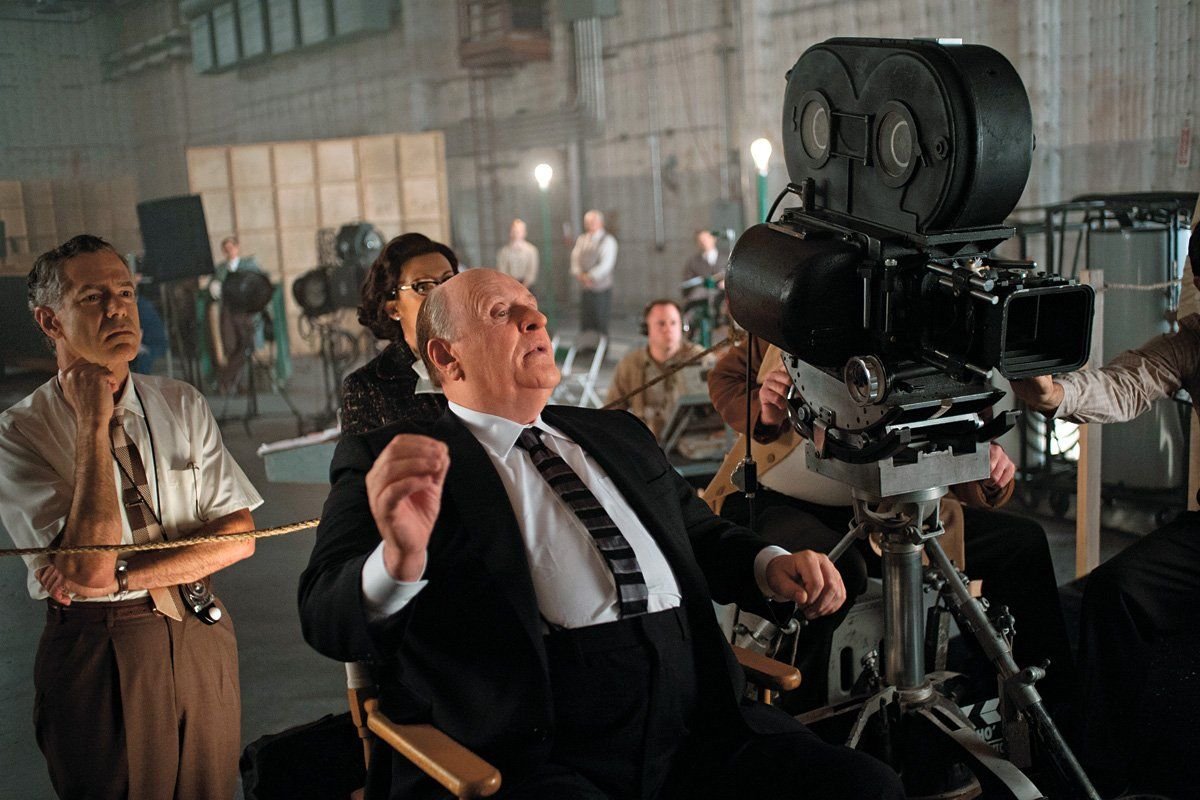

"There's no question about his work. He was one of the greatest geniuses in the history of the medium," says Sacha Gervasi, the director of an ambitious, period-soaked new movie, Hitchcock (in theaters Nov. 23), about the filming of Psycho, the masterpiece for which Hitchcock is best remembered today, though in fact it signaled a sharp break from all that had gone before. What remains is the mystery of Hitchcock's true nature. As Gervasi puts it: "What kind of a person was he?"

Hitchcock tries to answer this question, through a layered reimagining of the man that shows him rebelling against the lords of the studios in their waning days. Gervasi, whose first film was the prizewinning rock-and-roll documentary Anvil!, sumptuously re-creates the Paramount "dream factory" of the late 1950s: the prefabricated stage sets and make-believe city streets, the executive conferences in mahogany suites, the cumbersome editing machines, the small army of lackeys and assistants. Hitchcock, impersonated by Anthony Hopkins, is neither monster nor caricature, but a fish-out-of-water artist struggling to maintain his subversive vision in this strangely stodgy and repressed world.

Hopkins, with his antic intelligence, slyly peels away the layers of Hitchcock's familiar cartoon image—the swollen girth encased in undertaker's black suit, the comically plummy accent with its Cockney traces. He discloses a creature of ravening appetites who drains martinis in a single noisy slurp and, armed with pruning shears, assaults the overgrown hedges on his large estate with chain-saw ferocity, wittily recalling Hopkins's best-known performance, as Hannibal Lecter, one of the many monstrous stepchildren of Psycho's Norman Bates.

Most striking, the film explores Hitchcock's relationship with his wife, Alma Reville (Helen Mirren), her husband's chief collaborator. The unique "Alfred-Alma dynamic," in Gervasi's phrase, is well known to cinéastes. Born a day apart in 1899, the two met at Islington, the British film studio, and fell into giddy collaboration, though Alma, acknowledging Hitchcock's genius as well as the low ceiling for women, subordinated her career to his. His full partner, she helped cast his films and also selected and often rewrote scripts (she received a writing credit on the classic Shadow of a Doubt).

But her specialty was "continuity." As Hitchcock vividly shows, she surpassed even her detail-minded husband in her keen grasp of the integrity and consistency of a movie, from the logic of its story through the characters' clothing, expressions, and gestures. Gervasi quotes the critic Charles Champlin: "The Hitchcock touch had four hands and two were Alma's." Gervasi adds, "She had a massive role, and was the final arbiter of taste. If she said something was good, it was good. If she said it wasn't, it wasn't. Hitchcock very much deferred to her."

Alma's half-hidden career has steadily emerged in recent years. It is the subject of the memoir by the couple's daughter, Pat Hitchcock O'Connell (who herself acted in a number of Hitchcock films, including Psycho). Alma also figures in Stephen Rebello's book Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho, the main source text for the script (by John McLaughlin) of Hitchcock. Mirren brilliantly captures Alma's subtle depths and quiet yearnings. The dutiful Hollywood wife—consummate hostess and cook—she nurses her own ambition and detests -Psycho as "low-budget claptrap." It is Alma who offhandedly suggests the heroine be killed off half an hour into the film (in defiance of Hollywood convention) and recommends Anthony Perkins (with his rumored secret homosexual life) in the role of Bates. And it is Alma who confidently takes command of the production when her husband is bedridden and then rescues the final cut in the editing room, spotting telltale slipups and also insisting that the pained violin shrieks in Bernard Herrmann's score be restored in the crucial shower scene.

Film buffs will debate the liberties Gervasi has taken, beginning with the opening, which re-creates one of the crimes committed by Ed Gein, the serial killer who inspired the script for Psycho; the purpose, plainly, is to remind us that even the grisliest pulp often originates in actual events. And Gervasi shrewdly anchors his story in the concrete realities of America in 1959, making us see why Hitchcock, who turned 60 that year, feared he had become stale. At the time no one else thought so. His previous film, North by Northwest, had been a smash—for Hitchcock and its stars, Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint, combining box--office gold with critical praise. The movie is in fact vintage Hitchcock in his slickest high studio mode. But viewed today, its atmosphere feels jarringly false, especially its picture of an America lacquered in complacent Technicolor kitsch—the improbably "elegant" dining car, where the romantic couple share a meal, the glowing interiors and perfectly tailored costumes.

The falseness had begun to rankle Hitchcock—as did his vassalage to the imperious philistinism of the studios, the decorum that overrode the claims of art. He was at the top of his game, but "anesthetized and constrained by success," as Gervasi puts it. "He didn't want to be the old guard stuck in an old way of filmmaking, only making movies with pretty movie stars." Though the studios courted him for the choicest projects, he was ritually passed over at Oscar time. (Remarkably, he never won an Academy Award for best director.) There was also the ordeal of codes and censors, of a suffocating docility to public expectation that nonetheless failed to deliver what the public really wanted: genuinely wrenching experiences.

Meanwhile, he was a keen student of continental film, where a new wave of auteurs had torn off the straitjacket. He had been dazzled by Les Diaboliques ( 1955 ), Henri-Georges Clouzot's ingenious tale (starring Simone Signoret) of a brutal murder plot, with a twisty ending that had jolted audiences. "It was a new type of filmmaking, visceral and real," Gervasi says. Hitchcock, desperate to reclaim his place at the forefront of cinema, decided "he could take a leaf out of their book and beat them at their own game." The risk was great. Paramount wouldn't touch Psycho. It was beneath Hitchcock, the king of glossy thrillers, and would disorient audiences. So he mortgaged his house to help bankroll the $800,000 budget and economized by using the crew that did his popular television program, -Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Still, he worried. "What if it's another Vertigo?" he frets to Alma, in one of the film's best jokes. The greatest of all films had baffled critics. It failed to make The New York Times's 10 Best Films of 1958, losing out to Gigi and Damn Yankees, among others. The Oscar had gone to The Defiant Ones, Stanley Kramer's earnest ode to racial understanding. Hitchcock was primed to shake audiences up instead of flattering them.

And this leads to the fraught question of Hitchcock's relationship with women. It is impossible to avoid the increasing misogyny in his life and work. While Hedren's experiences may have been extreme, it is nonetheless true that Hitchcock did treat her and other Galateas, Vera Miles for one, abusively on the set, even as he tried to mold their personas, at times choosing the clothes they wore off screen. "Hitchcock's deepest fear," says Gervasi, "is that he's a terrible, terrible person. He, too, would be capable of these horrific crimes"—Norman Bates's, he means. The parallels are inescapable. Hitchcock, too, was a mama's boy, who lived with his mother until the age of 27. And he seethed with envy of handsome leading men like Grant and Stewart, who attracted in real life the beautiful women he possessed only through the vehicles he made for them.

Where the demonizing accounts go awry is in their presumption that Hitchcock himself was somehow unaware of the darker aspects of his own nature. Doubtless he suppressed his own desires, or projected them on the icy blonde stars he favored. But that doesn't mean he didn't confront them. On the contrary, Gervasi says, "I think we all sense he's working something out, sublimated rage toward women, obsession with sex, death, and murder." Self-knowledge, not denial, led him to the low-budget depths of Psycho, and its explicitness, which in turn led to fraught negotiations with Hollywood censors. One of the best moments in Hitchcock comes when the objection is made not to the lascivious stabbing of the character played by Janet Leigh in the original (and here by a wholesome Scarlett Johansson), but to the inclusion in the scene of a flushing toilet bowl.

Hitchcock seems to relish these showdowns, a chance to outfox the guardians of family values. With equal relish he informs cast and crew that filming will coincide with the last days of the Eisenhower administration. (In fact the film was shot, with wizardly dispatch, from late November 1959 to early January 1960.) Hitchcock's message, unemphasized but unmistakable, is that the 1950s are over, and a new decade will begin—less inhibited, less reticent in its exploration of sex and violence and the connection between the two. The codes and censors will soon disappear. And it is Hitchcock who pointed the way. Psycho's offspring would soon populate, and revive, American film. "Bonnie and Clyde, The Wild Bunch, and Quentin Tarantino can be traced directly back to Psycho," Gervasi points out.

So, for that matter, can Jaws, the Star Wars franchise, and the Coen Brothers' flirtations with nihilism. None would have been possible without Hitchcock's bold attempt to break through the suffocating standards of his day—not to satisfy critics, but to arouse audiences. Watching the original Psycho today, it is not just the knife thrusts, which in Hitchcock's mind conveyed "tearing at the very screen, ripping the film," that stay with us. It is also what precedes and follows: the brutal choreography of images, the almost orgasmic pleasure on Janet Leigh's face as she feels the needling shower spray, and then, after she has been attacked, the surrealistic image of one enormous lifeless eye, her face now a mask glistening with water drops.

Psycho, Pauline Kael would say, "shocked me in a way that made me feel that it was a borderline case of immorality ... because of the director's cheerful complicity with the killer." And the memory is permanent: it "stayed with me to the degree that I remember it whenever I'm in a motel shower." This, she added, is "what a theatrical experience is about: sharing this terror, feeling the safety of others around you, being able to laugh and talk together about how frightened you were as you leave."

Psycho offers more than horror—and more than horror aestheticized. It recovers our most primal urges, and does it through the most calculated of techniques. The complicity includes ourselves. In the presence of such mastery it is futile to ask whether the man who created it was "good" or "bad." Hitchcock takes us somewhere few of us will dare, or can bear, to go alone. "We're all in our private traps," Norman Bates tells his victim, in the quiet prelude to his assault. "I don't mind mine anymore." Hitchcock, in creating this great film, wanted above all to spring free of his own gilded cage, and to take us with him. And because we have no choice, we follow.

Hitchcock knew this. And so does Gervasi. At the premiere of Psycho, we watch Hitchcock, by himself in the theater -lobby, lifting his arms like a conductor, lovingly setting the tempo for an audience he can't see as its screams crescendo toward their climax.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.