Why is the Brazilian right afraid of Paulo Freire?

The Bolsonaro administration has used a misleading caricature of the educator to justify its assault on public education.

The late Brazilian educator Paulo Freire (1921-1997) was a prominent figure in the 20th-century critical pedagogy movement and the celebrated author of the ground-breaking 1968 text, “Pedagogy of the Oppressed.” Freire’s seminal work proposes a dialogical method of teaching literacy that nurtures conscientização – critical consciousness – and encourages participation in political struggles. According to a 2016 study, “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” was the third most cited book in the social sciences. As Daniel Schugurensky writes in his 2011 intellectual biography of Freire, “no other educational thinker from the global south has attracted such wide international attention to his or her ideas.”

Yet Freire’s legacy remains a contentious issue in contemporary Brazil. The Brazilian right tends to portray Freire as a dangerous subversive who planned to indoctrinate the youth. The right-wing administration of President Jair Bolsonaro has used this misleading caricature to justify its assault on public education.

In speeches and interviews, Bolsonaro and his allies represent Freire as a kind of leftist boogeyman whose influence needs to be purged from the Brazilian education system. On his campaign trail, Bolsonaro boasted to his supporters that he would “enter the education ministry with a flamethrower to remove Paulo Freire.” Abraham Weintraub, Bolsonaro’s now former minister of education (he recently left for a contentious position at the World Bank), blamed Freire for Brazil’s poor education rankings and likened Freirean pedagogy to “voodoo without scientific proof.” Similarly, Brazilian philosopher Olavo de Carvalho, who is known as “Bolsonaro’s guru,” dismisses Freire as a “pseudo-intellectual militant” who produced “a collection of tricks to reduce education to sectarian indoctrination.”

Leftist indoctrination

Ultimately, Bolsonaro and his supporters believe that Freire was a deranged revolutionary who deserves to be stripped of his title as Brazil’s patron of education. Yet these insults and accusations are not unique or novel. In fact, members of the Brazilian right have slandered Freire in this manner for over half a century.

We’ve got a newsletter for everyone

Whatever you’re interested in, there’s a free openDemocracy newsletter for you.

The military junta regarded Freire as an “international subversive” and “a traitor to Christ and the Brazilian People”

Undoubtedly, Freire played a significant role in the history of Brazilian politics. In 1963, he served in João Goulart’s center-left government as the president of the National Commission on Popular Culture. The committee introduced an educational campaign that planned to use Freire’s teaching methods to bring literacy to 5 million Brazilian citizens. At the time, literacy was a requirement for voting, and the Goulart government hoped that Freire’s campaign would increase electoral participation.

Brazilian oligarchs and landowners feared that the campaign would cause peasants to form associations and vote for land reform. The influential newspaper O Globo claimed that Freire’s methods were too subversive because they encouraged people to think about political and cultural change. In short, the Brazilian right sensed that Freire’s adult literacy initiatives posed a threat to traditional hierarchies.

In 1964, the Brazilian military overthrew the Goulart government in a coup d’état and arrested Freire. According to Moacir Gadotti, the military junta regarded Freire as an “international subversive” and “a traitor to Christ and the Brazilian People”. During Freire’s trial, one of the judges even accused him of plotting to transform Brazil into a communist state. Freire was imprisoned for 70 days before he received political asylum at the Bolivian Embassy in Rio de Janeiro. In exile, Freire held a visiting professorship at Harvard University, worked as a special education adviser to the World Council of Churches and co-founded the Institute for Cultural Action.

When Freire moved back to Brazil in 1980, he became one of the founding members of the Worker’s Party (PT). He supervised many of the PT’s adult literacy projects and served as municipal secretary of education in Sao Paulo between 1989 and 1991. Under the leadership of Freire’s fellow PT co-founder Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, widely known as Lula, the PT won the 2002 general election. The Brazilian right is keen to stress this connection between Freire and Lula. Bolsonaro and his supporters interpret President Lula’s modest educational reforms, such as funding for underprivileged indigenous and Afro-Brazilian university students, as a continuation of Freire’s supposed plot to transform Brazil into a communist regime.

The right to education

Since Bolsonaro’s inauguration in January 2019, his administration has proposed and implemented several policies that aim to tackle the alleged scourge of Freire-inspired “leftist indoctrination” in Brazilian schools and universities. In April 2019, Weintraub threatened to divert funding from sociology and philosophy university departments to disciplines such as engineering and medicine that would offer an “immediate return” to the taxpayer. Critics of this policy, such as Stephanie Reist, claim that Weintraub sought to defund sociology and philosophy departments because he assumes that they are hotbeds for left-wing activism and “cultural Marxism.”

The defense of Freire’s legacy has become an enduring symbol for defending the right to education

Several days later, Weintraub declared a 30% budget cut for all federal universities. Commentators point out that these funding cuts are part of a larger campaign to undermine and demoralize resistance to the Bolsonaro regime. Weintraub hoped that these cuts would discourage federal universities from hosting political organizations such as the Landless Worker’s Movement on their campuses.

Additionally, Weintraub endorsed the witch-hunting tactic of recording “leftist” teachers in classrooms. The right-wing political movement, School Without Party, whose founder Miguel Nagib once described Freire as the “patron of indoctrination,” popularized the idea of getting students to film teachers who are suspected of promoting leftist ideology. Members of the movement hope that Bolsonaro’s administration will replace this purported “leftist indoctrination” with a “neutral” education that reinforces traditional moral values.

Those who are familiar with “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” will know that Freire believed that education was never neutral. For Freire, education is either a form of emancipatory action or an instrument of domination. In Freire’s terms, the Brazilian right wants schools and universities to convert students into “adapted persons” who will conform to existing hierarchies and refrain from questioning the political order. As Freire writes in the preface to “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” the “rightist sectarian … wants to domesticate men and women.”

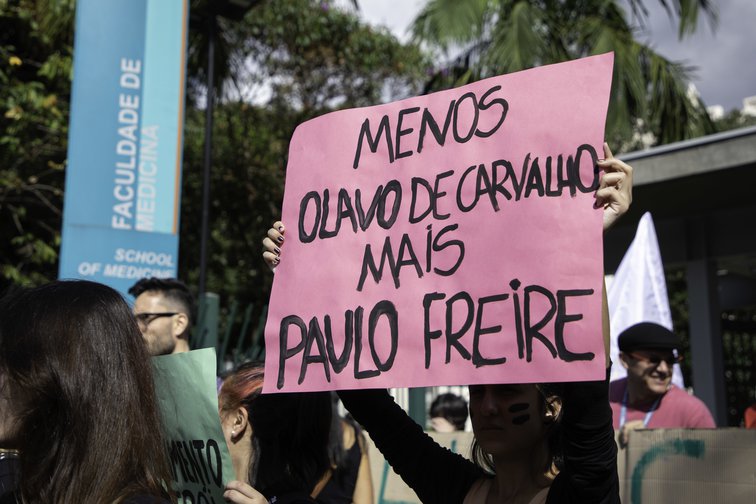

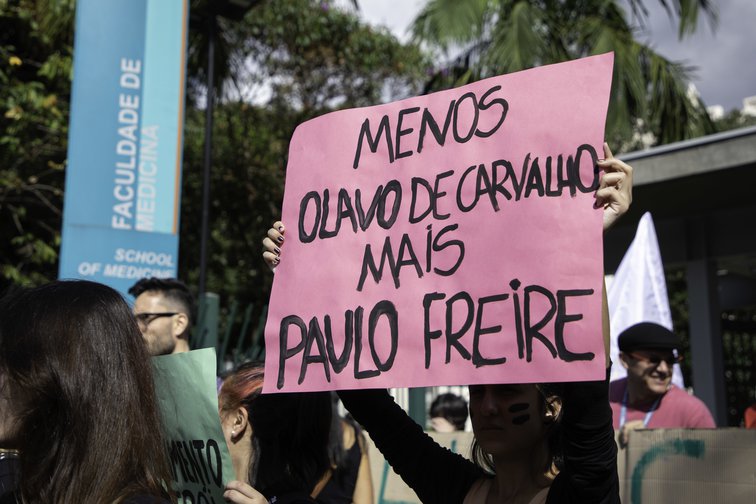

Yet Brazilian students and teachers refuse to tolerate Bolsonaro and Weintraub’s efforts to “domesticate” them. In response to Weintraub’s proposed funding cuts, mass protests took place in over 200 cities across the country, described as “education tsunamis.” Similarly, Teachers Against ESP continues to criticize and oppose the government’s plans to erase the topics of slavery and LGBTQ rights from the curriculum.

Over the past year, more people have become interested in Freire’s work. According to publisher Paz e Terra, sales of “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” increased by 60% in the first half of 2019 compared to 2018. In a recent interview, his widow, Ana Maria Freire, quipped that Bolsonaro has inadvertently boosted Freire’s popularity, saying that Bolsonaro “is encouraging the sale of Paulo’s books!” During the protests, countless banners and placards displayed Freire’s name and face. The educational researcher Inny Accioly opines that “the defense of Freire’s legacy has become an enduring symbol for defending the right to education.” Despite the Brazilian right’s countless attempts to distort his legacy, Freire’s life and work will continue to inspire and guide those who believe that education should be a critical endeavor that aids the task of liberation.

This piece originally appeared in the Fair Observer and was republished with permission. Click here to see the original.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.