THE "ICE FLOWERS" OF SNOWFLAKE BENTLEY

JERICHO, VT — Back in the 19th century, folks in these parts didn’t know much about snow but they knew they damn well didn’t like it. And there was a lot of snow not to like. This little two-steepled village near the Canadian border still gets plenty of snow each year, and to hear folks tell it, there used to be more.

Whole days of snow. Drifts over the eaves. Snow in April, May, June. Tunnels to the barn. So what was that crazy Bentley boy doing out in a Nor’easter? With a camera?

Home-schooled by his mother, Wilson Bentley grew up oddly curious and curiously odd. By the 1880s, most boys in Jericho were content to farm through the short summer, then huddle around the wood stove. But snow did not close down Wilson Bentley’s world. Snow was the curtain that revealed it.

“Always, right from the beginning,” he remembered, “it was the snowflakes that fascinated me most. The farm folks up in this country dread the winter, but I was supremely happy.”

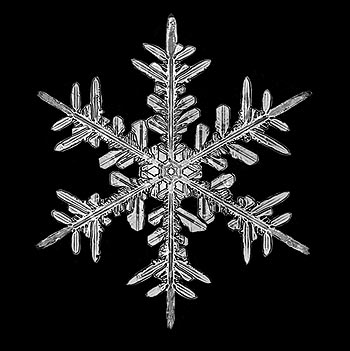

Children knew. Catch a falling flake on a dark glove and behold! A tiny star! But to adults, all those damn snowflakes looked alike. Then, for his fifteenth birthday, Wilson Bentley got a microscope. When he took it outside, a lifetime of wonder began.

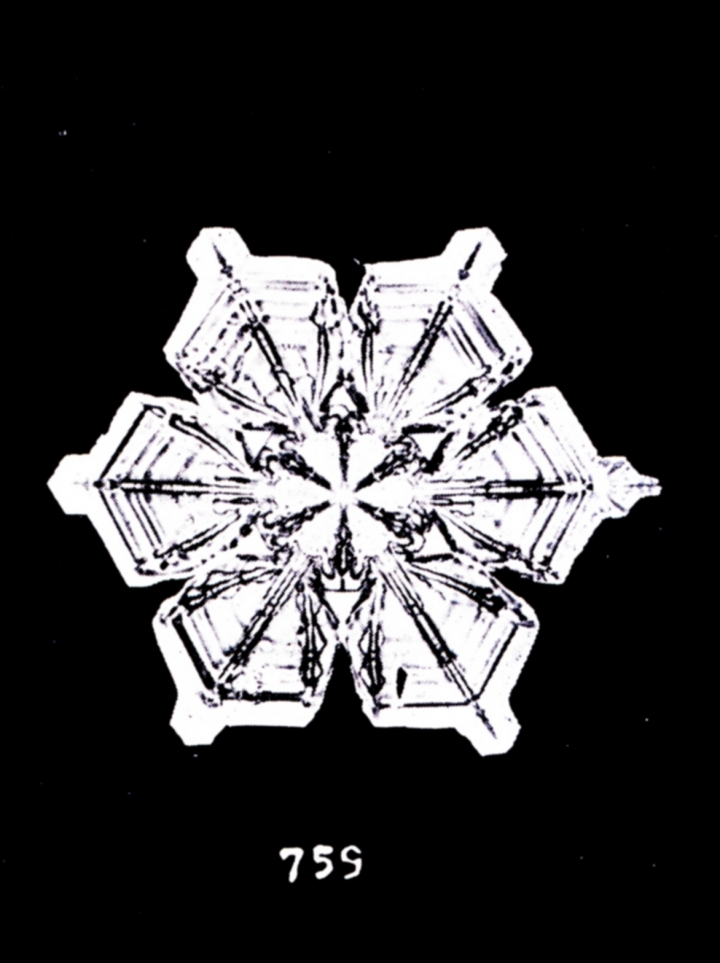

Flakes on glass slides melted in seconds, yet those seconds revealed the miracle. A snowflake was not a clump of ice. Each was a delicate crystal. Six-sided, every one. With frozen tendrils and filigrees, like doilies on his mother’s kitchen table. Wilson Bentley had to show someone, but everyone was inside, huddled around the wood stove.

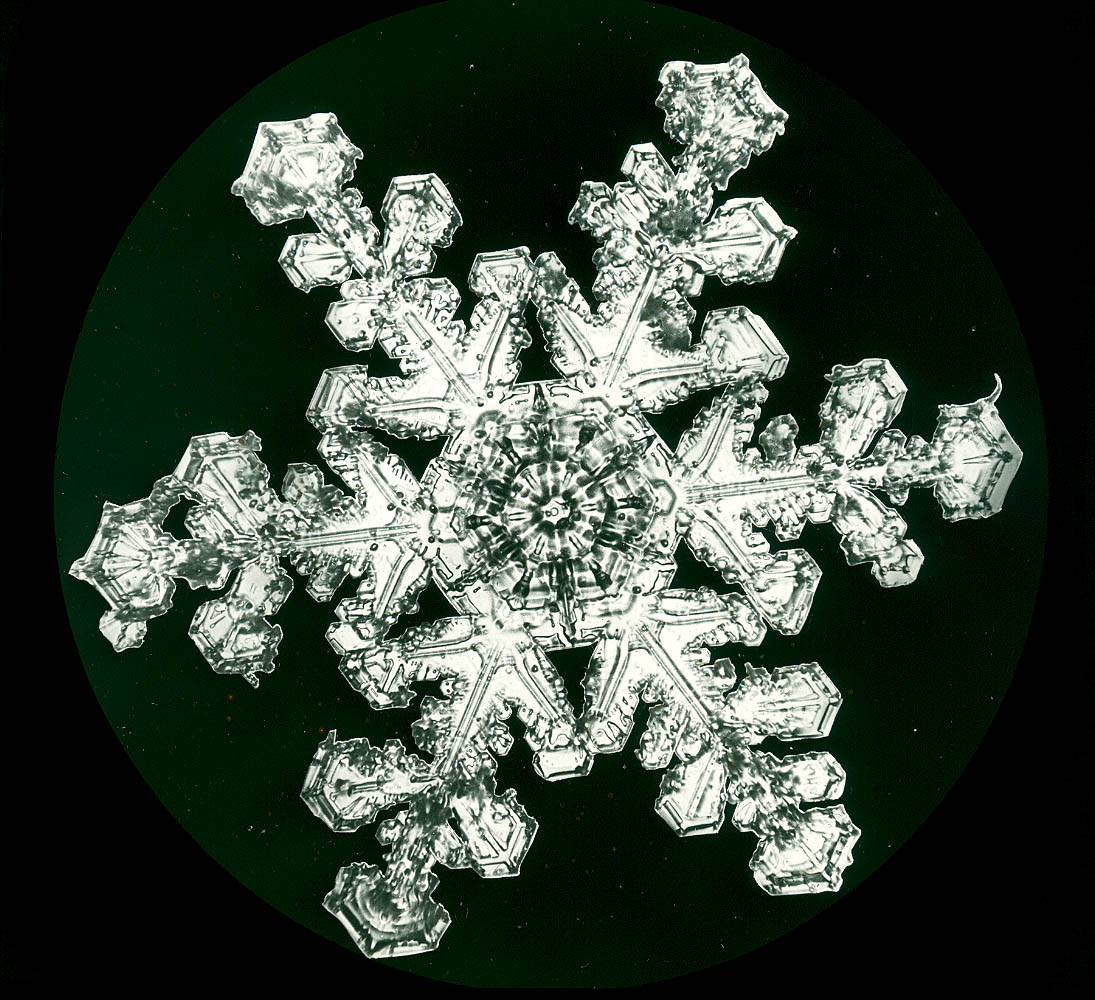

He tried sketching flakes, but they melted. Maybe if he had a camera? Bentley’s father scoffed, but his mother, a former teacher, knew curiosity when she saw it. Two years after he got his microscope, Bentley’s parents bought him a camera. Figuring out focal length and exposure time took two more years. Then on January 15, 1885, Wilson Bentley took the first photograph (below) of winter’s everyday wonder — a single snowflake.

“I felt like falling on my knees,” he said. But more flakes were falling, more doilies to capture. "I found that snowflakes were miracles of beauty,” he recalled. “And it seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others.”

For the next 45 years, while Jericho farmed and froze, Wilson Bentley photographed snowflakes. He soon jerry-rigged a trusty system. A black tray to catch flakes. A feather from his father’s chickens to move the flake onto a slide. A camera with a focal length extended on wooden wheels. Exposure time — 8 to 120 seconds. Freeze frame. Freeze flake. Click. . .

In 1898, this home-schooled Vermonter was the first to claim that no two snowflakes are alike. Hundreds of photos suggested this, but Bentley also did the math.

Snowflakes, he realized, form as they fall. Temperature, humidity, and other factors vary with altitude. Thus, each falling flake is formed by hundreds of changing conditions. As the combinations multiply exponentially, the variations soar to ONE followed by hundreds of zeros. More designs than molecules on earth. No two alike, each an “ice flower.”

In the early 1900s, when Bentley began writing for National Geographic, “no two alike” became common wisdom. Children were cutting “snowflakes” out of folded paper, and Bentley’s photos, if not his name, were soon known worldwide. Still, every time it snowed in Jericho, “The Snowflake Man” emerged from the cluttered farmhouse where he lived his whole life. And there he was out in the drifts. . . “I guess they've always believed I was crazy, or a fool, or both,” Bentley said of his neighbors.

Just before Thanksgiving in 1931, Bentley received copies of his only book, Snow Crystals. Two weeks later, he was caught out in a snowstorm. He had to walk six miles home. He died of pneumonia that December.

For decades, his name was forgotten. Then a former research scientist for General Electric began to track down the man responsible for 5,000 crystalline images. Few in Jericho remembered. Ask Joe down the road a piece. Or what about Mary Agnes — she knew the ol’ coot. Hey, isn’t there a Bentley still in town? Lives up by that tree? Big ol’ birch, you can’t miss it...

With time, Jericho took pride in its native snowman. In 1973, the Jericho Historical Society bought the Old Red Mill, a five-story grain mill dating to the Civil War. The mill now houses the Wilson A. Bentley Exhibit, with photos plus his camera and microscope.

In 1999, a children’s book, Snowflake Bentley, won the Caldecott Medal for illustration. Today, Bentley’s “ice flowers” can be viewed online, along with video tributes to the curious man who revealed ordinary snow, lots of it, as the miracle it was made to be.