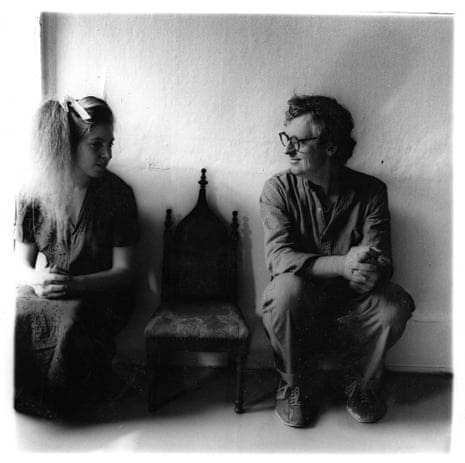

Betty Woodman remembers with perfect clarity the day her daughter Francesca took the photograph. It was in La Specola, Florence’s museum of natural history. “Francesca was fascinated by La Specola,” she says. “She wanted to work there, but it wasn’t going to be straightforward. So she made friends with the guard and he let her in after hours. He got very nervous about it – I think he was more interested in her than in photography – so she asked me to go with her. I had to sit in a room outside, but if she squawked or sounded like she needed help, I was to go right in.” Francesca’s father, George Woodman, interrupts: “What she means is, if the guard pinched her bottom, Betty would be there.”

Consider the image in question (facing page, top left) and you pick up a powerful sense of this backstory: it has a wonderfully secretive quality. What happens in a museum when all the visitors go home? In this one, a kind of ghost appears in the form of Woodman, who can be glimpsed behind a large vitrine in which sits the huge and alarmingly toothy skull of some unidentifiable animal. “Francesca couldn’t make her mind up,” says Betty. “First, she wanted to be naked. Then she thought she’d wear a leotard.” Not that I should get the wrong idea. “This wasn’t a performance. She was concentrating on the picture. That was why she didn’t want people around. She didn’t want any distractions.”

I look at the photograph again, but I can’t agree. Francesca’s head is tilted back, her mouth is slightly open, her fingers are stretched wide over the glass of the vitrine. Surely it is quite clear that she has seduction in mind. However wild, however toothy, however dead, this strange animal, you gather, will soon be putty in her hands. The sequence, titled Space (1975-6), is one of several photographs that will be included in Zigzag, a new exhibition of Woodman’s work at Victoria Miro, Mayfair. It’s a show that Betty and George hope will highlight another side of their daughter’s brief but brilliant career.

Woodman committed suicide in 1981, at the age of just 22. As a result, it is her self-portraits – funny, artful, neurotic, and occasionally painfully honest – that have always attracted the most attention. People want to see this extraordinary lost girl; they remain convinced that her primary subject was herself. But her parents refute this.

“People do latch on to certain images,” says Betty, on the telephone from their home in Italy. “Some have become iconic and, sure, those are great photographs. But she produced over 800 works, and we’d like the others to be seen, too.” The exhibition is entitled Zigzag because every piece is a collection of angles, whether formed by legs or arms, fabric pleats or unhinged doors. And while the artist herself is nearly always present, it is her limbs and torso we see most often, not her face. These images reveal Francesca’s talent for composition, for light and shade, rather than her way with storytelling, her tendency to (self) dramatise.

“People like to mythologise artists,” says George. “But it’s the real facts that are of interest to us.” Fans and critics alike, he and Betty believe, tend to ignore the humour in his daughter’s work, and often claim for her a feminism she wouldn’t have recognised (these people are perhaps provoked by her nakedness, by the way she pinches and pulls her flesh as if it were all just too much).

“You can reinterpret her pictures, if that’s your point of view,” says Betty. “But I don’t think that was there. Everybody was tied in knots about politics in the 70s, but she wasn’t interested.” Their memory of Francesca is that she wasn’t a “deeply serious intellectual”; she was witty, amusing. “She had a good time,” says Betty. “Her life wasn’t a series of miseries. She was fun to be with. It’s a basic fallacy that her death is what she was all about, and people read that into the photographs. They psychoanalyse them. Young people in particular feel she’s talking about them, somehow. They see the photographs as very personal. But that’s not the way I approach them. They’re often funny.” The photographs in Zigzag include playful visual jokes: a pair of fingerless “gloves” made from the bark of tree and modelled by Francesca, whose arms are raised so as to resemble the spindly trunks of the birches nearby; a disembodied pair of legs mirroring a charred-looking V-shaped groove in the ground, as if her body left this impression behind when she unaccountably fell to earth.

Life as a working artist can be hard: the Woodmans, both artists themselves, know this. “It’s terrible!” yelps George. But it wasn’t Francesca’s work that troubled her; it was the art world, competitive and precarious, that she found scary. In a published essay about his daughter, George quotes a line from her gnomic Gertrude Stein-inspired journal: “Today I came home from Newport seething with ideas and a new hat.” Written in the autumn of 1975, when she was 17, it captures both her predominantly ironic tone, and the fact that her brain was always fizzing. “We were artists, and all our friends were artists,” he says. “So that was normal for Francesca. But she didn’t try to do what we had done [George is a painter, Betty is a ceramicist]. She focused on photography early on, a medium in which neither of us worked –she struck off on her own. I gave her a camera when she was 13, and she just liked it. She had 50 million ideas.”

Why did she put herself in the images? Francesca once said that it was just a matter of “convenience”: she was always available, whereas finding a model would take time. “I do think that was it,” says Betty. “Though telling yourself what to do is also much easier than telling someone else to smile, or to look this way or that.”

In her lifetime, Francesca Woodman wasn’t famous. When she died, she’d only just ceased to be a student. But in the years since, her fame and influence have grown exponentially (most recently, it hovered over Joanna Hogg’s film Exhibition, in which Viv Albertine played an artist who covered her body in gaffer tape, a trick Woodman tried more than 30 years before). Today, her work is valuable and sought after. What is this like for her parents? To walk into a gallery and see her, so young and so vulnerable, hanging on its walls?

“For us, it’s a bittersweet thing,” says Betty. “We don’t have much distance from it.” There is a pause, and for a moment I wonder if we have lost the line. But then she’s back. Francesca, she believes, might eventually have begun to work in other media. “We have some beautiful paintings of hers. In fact, we just found one all crumpled up here in Italy, and we had it restored and stretched and it’s wonderful. But, yes. The question is always there: what would she have done if she had gotten over the crisis she was in?”

Francesca Woodman was born in 1958, and grew up in Boulder, where her parents belonged to the fine art faculty at the University of Colorado, though she also spent a great deal of time in Italy, where the family has a house in Antella, near Florence (later, she would spend a formative year in Rome as a college student). At boarding school in Andover, Massachusetts, she took photography classes, and it was during this period that she began to explore some of the ideas that would appear in her later work (such as the strikingly grown-up series of photographs in a cemetery in Boulder, in which she appears naked among the headstones). By the time she enrolled as an undergraduate at the Rhode Island School of Design, she was already fully committed to a career as a photographer; those who knew her say she arrived on campus in a league of her own.

“She was kooky, and at first I didn’t want to be anywhere near her,” says her friend, writer and journalist Betsy Berne. “We were in the same dorm, and I couldn’t get away from her. She seemed to have been born in the wrong century – she was totally outside pop culture; she never watched TV; she couldn’t have cared less about music. But if she wanted something, she was going to get it, and when we moved to New York [in 1979], I sublet the place she lived in and that’s when we became close. She was very loyal and intense. She was the kind of person you either loved or hated.”

What did Berne make of her work? “I loved it. She was way more sophisticated than the rest of us. She was 21, and yet so many people were jealous of her. But in your 20s, everything feels so urgent. You think you’ve got to be famous in 20 seconds, all the more because she had been making this very good work from the age of 14. The pressure was intense.” Like Betty and George, Berne believes Francesca’s photographs are too often viewed through the sombre prism of her early death. “Let me just emphasise: she had a great sense of humour. There’s a great deal of wit in them, and irony.” Unlike the Woodmans, however, she insists her friend was political. “We used to make fun of the feminists, but we were feminists ourselves. We read such a lot.” In the past, Woodman’s suicide – she jumped off a building in lower Manhattan – has been linked to a funding application that had been turned down. Berne disputes this. “She had an illness: depression. That’s all there is to it.”

The first solo shows of her work opened in 1986, and drew a great deal of attention. More crucially, she was championed by American critic Rosalind Krauss, who saw her photographs – perhaps somewhat predictably – as an attempt to resist the male gaze (Krauss has written that Woodman exhibits a tendency to “camouflage” herself, attempting to “hide” even as she stands in front of the camera). Although some continued to see the work as adolescent and excessively narcissistic, others began to regard Woodman as the last of the great Modernist photographers, a line that may be traced back to Man Ray and the other surrealists. Later, Cindy Sherman, a contemporary of Woodman’s, became a fan – and perhaps Woodman’s influence can also be seen in the work of Nan Goldin and David Armstrong.

“Her appeal has grown rather than waned,” says Corey Keller, a curator of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. “Art students are drawn to the conviction she brought to her work and, in contrast to the cool slickness of the digital, it embraces tactility and decay in a very sensual and seductive way.” Keller sees Woodman’s youth not as a liability, but as the source of her potency, though she admits the issue of her self-portraits continues to be fraught. “They are certainly an expression of selfhood. She’s not interested in images of women in general, for example, and even when the subject of the photograph is not herself physically, one always has the sense it is about her psychically.”

In the end, you can only return to the images themselves, the best of which are not only beautiful, but endlessly beguiling. Of those that will appear in Zigzag, the one I love the most consists mostly of a huge pleated curtain, on top of which are balanced three large, decaying leaves. Woodman has been pushed into a corner by this weird construction: we see only an elbow and half of her face; her eyes are cast down. It would seem deathly, funereal, if it wasn’t for the fact that over the whole thing there falls, like a blessing, a bright rectangle of sunshine. There is something so subtle about it, so charmingly odd, that my fingertips tingle when I see it. It makes me feel covetous, and strange, and somehow powerfully female.

Francesca Woodman: Zigzag is at Victoria Miro Mayfair, London, 9 September to 4 October (victoria-miro.com)

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion