As part of Storylines, an ongoing exhibition of contemporary art associated with larger narratives, the Guggenheim museum in New York is offering a rare delight of cinematic maximalism – and masochism – with marathon screenings of artist Matthew Barney’s complete Cremaster Cycle. The five films, produced out of order between 1994 and 2002, make for a nine-hour helping of moviegoing, including short restroom breaks, a 90-minute respite for lunch and an “Oh God, let me feel the sun on my face” interlude.

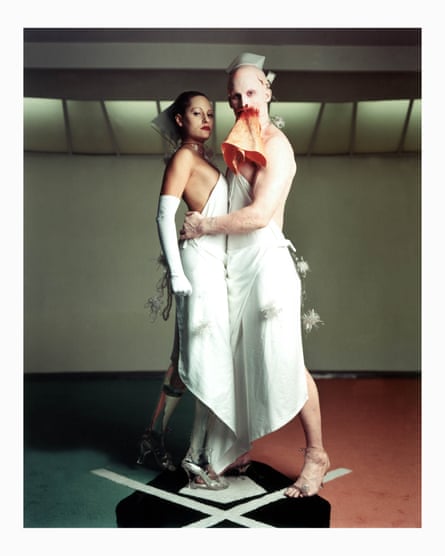

The Cremaster Cycle is somewhere in between a traditional film and an art installation. It isn’t too easy divining a plot, but each entry offers a great deal of “business” to follow, usually oddly dressed characters trying to accomplish some sort of strange task. This can range from chopping up a room full of raw potatoes with bladed shoes to a kit of pigeons bringing a man’s penis to erection with ribbons.

These films are not available on home video. Well, that’s not entirely true. Twenty DVD collections in elaborate packaging were sold for $100,000 a piece. In 2007, just one-fifth of the series (Cremaster 2) was sold at auction for over $500,000. The disc came in a case “made from hand-tooled saddle leather, sterling silver, polycarbonate honeycomb, beeswax, acrylic and nutmeg”.

On a gorgeous Saturday in July, Guardian US arts editor Alex Needham and film critic Jordan Hoffman took the plunge and, equipped with a few protein bars, exposed themselves to some lengthy art. Below is a conversation that happened via email once they had wiped the melted paraffin from their eyes.

Jordan: I’ve done my share of movie marathons. I’ve done Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó (seven hours and 12 minutes) and Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 (12 hours and 53 minutes, spread out over two days), plus the Alamo Drafthouse’s 24 hour Butt-Numb-a-Thon, but what makes this one different is its museum aspect. In recent years I’ve used the phrase “could double as an installation piece” when discussing beautiful films with hard-to-reach narratives, movies like Terrence Malick’s To the Wonder or Carlos Reygadas’s Post Tenebras Lux.

But Barney really does live at the other end of that divide. The props created for his films are later sold as sculpture to collectors, and can be found in galleries and museums. The films are a part of a larger work, and, as such, I always expect to go into his movies with an expectation merely to “enter a zone”. What’s surprising is that, with the exception of a few stretches, these lengthy and somewhat mystifying sequences can also be enthralling in a traditional moviegoing way. What expectations did you have going in?

Alex: Movie marathons aren’t my thing but, as a man blessed with a long attention span, I’ve sat through a bunch of sizeable artworks, including a memorable nine-hour avant garde concert in Adelaide which included what sounded like a man rustling a crisp packet for 20 minutes. I’ve done a Ring Cycle; I’ve read Ulysses; I’ve done Einstein on the Beach (five hours) and Gatz (eight). The rare opportunity to spend seven hours immersed in Barney’s Vaseline-slathered universe seemed like one too good to pass up – although I did have second thoughts when Saturday morning saw New York drenched in radiant sunshine. We’d spend the vast majority of the day in a basement, albeit one designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

As for the Cremaster Cycle itself, I’d never seen it other than in still images. My only engagement with Barney’s work has been his great Drawing Restraint show at the Serpentine Gallery in London in 2007; I just missed his last film River of Fundament in Australia last year. So I was keen to get my hands dirty in the axle-grease and melted rubber of Barney’s automobile obsession – which brings us to the first in the series.

Jordan: The first, which is the fourth! The Guggenheim chose to show these films as they were produced, which is out of order. I think it’s a wise move, as they definitely grow, not just in terms of length (roughly 40 minutes to three hours) but in scope, grandeur, difficulty of production and quality of film stock. Part one features a lot of birthing imagery, and part five has some death, but that’s about all I could put together as a throughline. So seeing them in this fashion seems like a better buildup.

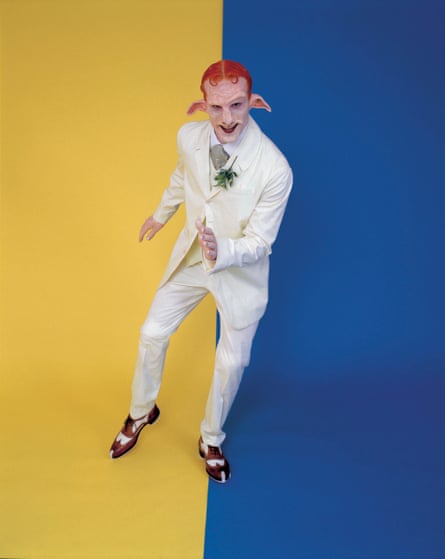

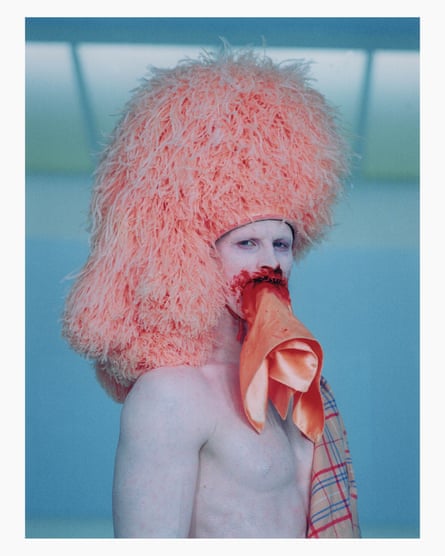

Cremaster 4 is, in some ways, the most energetic. Its twin actions include a motorcycle sidecar race around the Isle of Man intercut with a satyr tapdancing a hole through a tile floor. There are some androgynous fairies who put some oozing goo into the pockets of the satyr, which somehow transports to the racers. At least that’s how I interpreted it. It concludes with the satyr wiggling through an enormous wax anus (again, my interpretation) and emerging in the mud as the race concludes. We’re introduced to a lot of iconography that will recur throughout the cycle. If I knew more about the specific myths or legends this is riffing on, I might have a richer reaction, as I do with some of later aspects. Still, there’s not a moment of this 42-minute video that isn’t strangely spellbinding.

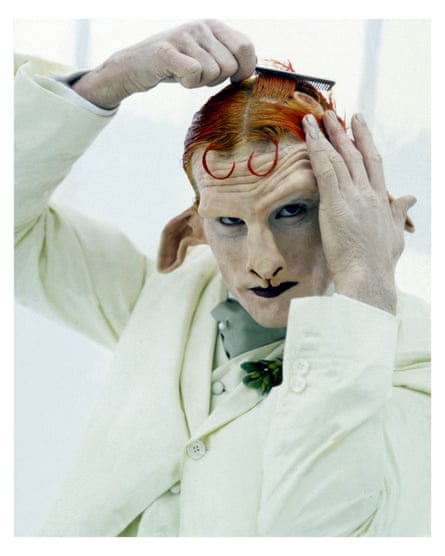

Alex: The Cremaster Cycle is named after the muscle that controls the height of the testicles; I’m sure every man has noticed its operation when swimming in a cold sea (or less pleasantly, getting socked in the balls). According to the sheet we got at the screening, the numbers of the films correspond to “the height of the gonads during the embryonic process of sexual differentiation” – one is the least descended, five the most. This was number four and it was a pretty male experience – all that racing around the Isle of Man (the name probably significant too); the closeups on leather-clad crotches and burly fairies. The film opened with Barney, playing the satyr with prothetic ears and nose, carefully combing fire-engine red hair over some raised, rather anus-like protuberances, before crashing through a hole in the pier and into the sea – where he kept tapdancing on the sea bed.

This film was the most raw in terms of film stock and technique, but that gave it an urgency and energy. It was a bold presentation of a very personal mythology without a map – we could guess the significance of the fairies rolling around on a bright yellow picnic blanket on a cliff top, but that was about it. Better to make like the race car drivers, strapped in, speeding through an unfamiliar landscape, all set to get covered in goo.

Jordan: All this makes for nice counterbalance in Cremaster 1, much more feminine in every respect. It opens with a touch of kitsch, a deep blue American football field in which a line of chorus girls dance to Mantovani-esque music. Above them float two Goodyear blimps which, set against the yellow markers of the field goal poles, resembling ovaries and a birth canal. Inside the blimp are women wearing Nazi-looking uniforms with the Goodyear logo pinned to them. It’s as good a moment as any to ask just how Barney is able to get major brands to let him reappropriate their intellectual property?

Further adventures inside the twin blimps include wax sculptures of what look like fallopian tubes and a table full of grapes that fall into animated shapes. (One has red, the other green, so you can keep track.) From a film-making point of view, the most striking moments include the choreography of the kickline dancers and how they recreate what’s happening with the airship. It’s very much a spin on Busby Berkeley Hollywood, but a touch sinister. The woman dropping the grapes may or may not be in discomfort inside her small chamber. The longer you linger in the strange spaces, the more you find vaginal imagery everywhere. The logo on the 50-yard line resembles an unfurled maxi pad.

Alex: Yes, that Mantovani-style music … I feel as though it’s been tattooed on my brain after hearing it continuously for 40 minutes. Like the music in the rest of the cycle it was composed by Jonathan Bepler, who pays homage to different styles from easy listening, like here, to grand opera in the next film, Cremaster 5. Cremaster 1 was a much less gnarly proposition than Cremaster 4, which ended with some tumour-type thing being unpleasantly probed with needles.

This elegant dance routine on a football pitch, controlled by a woman in the Goodyear blimp, was visually ravishing (Isaac Mizrahi designed the costumes, another instance of Barney managing to involve heavy hitters in these crazily ambitious and bizarre projects) but also eerie. The most dramatic moment for me came when a single, gigantic high-kicking chorus girl was shown with the two Goodyear Blimps attached to her wrists, prefiguring the next film’s sequence with the birds. Who knows what it was all about, but all the fallopian imagery seemed to point towards some kind of imaginative landscape before birth or even before conception, when all that exists are the possibilities of what a new person might be.

You’re right about the maxi pad, mind.

Jordan: Good to open with Bepler’s music when discussing Cremaster 5. This has one of those mesmerising scores that keeps you rooted all through the closing credits. It’s a pulse of minor key chords as pink beads bubble up in Budapest’s art nouveau Gellert baths. I cheated a bit and read an interpretation that says these final moments represent the last descent of the gonads, in which gender is determined. I’ll be honest and say this didn’t quite connect with me. But I was nevertheless taken with the striking imagery.

Cremaster 5 represents a larger production than 4 and 1. It is shot in a wider aspect ratio, with a more professional lighting rig. (Barney was still shooting on BetaCam.) It’s got some night imagery of a man on a horse on the Chain Bridge and Ursula Andress lip-synching as a woe-begotten queen in the Budapest Opera House.

In other words, it has numerous signifiers of being, for lack of a better term, a real movie. It’s a neat trick because, at least for me, you’re conditioned to fill in narrative gaps based off closeups and cutting schemes. As far as the plot of this 55-minute film is concerned, there’s a lot of pageantry, and another example of a man on a struggling climb. This time he’s going up the side of a proscenium, and while his goal isn’t exactly clear, it’s still engaging.

For me, though, I wasn’t quite as into Cremaster 5 as the other two, and maybe would have found it dull if it weren’t for the music. I had the good fortune to see River of Fundament and that five-hours-and-50-minute film (with two breaks) is about half sung through opera. You see some of the roots to that here. Do you want to try and explain what the pigeons were doing, or have we hinted at it enough?

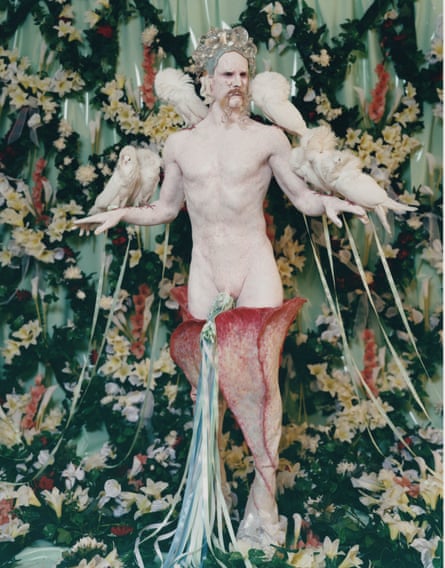

Alex: The pigeons are definitely one of the Cycle’s strangest and most beguiling moments. Andress as the queen and her two female courtiers look down through another anus-like aperture. They can see the Gellert baths, where Barney, in his role as her diva, is advancing slowly through pools filled with pearl-like bubbles which, turn out to be shaped a bit like the Cremaster emblem. Under the water, hermaphrodite water-nymphs tie ribbons to his penis – which isn’t an ordinary human penis but looks more like the roots of a plant. The ribbons are in turn attached to the pigeons. They fly upwards, facilitating an erection. Yes, it’s a full-on glorification of the male sexual and creative impulses, of the kind that annoys some feminist critics of Barney’s work no end. But I enjoyed the mixture of utter grandeur and ludicrousness – not exactly an unusual combo here.

In another scene, Barney, in the guise of the giant, stands on the Chain bridge between Buda and Pest and finally dives off. In other words, Cremaster 5 is as lavish and highfalutin as an early-80s pop video, and Ursula Andress made an alluring opera-singing queen, although her lip-synching wouldn’t have passed muster on a half-drunk drag act … even if she was attempting Hungarian, possibly Europe’s most impenetrable language.

Jordan: At this point in the programme there was a break – just enough time for a sandwich, a peek at some of the other work on display at the Guggenheim and to answer a few emails. Then it was Cremaster 2, a 79-minute entry shot on more cinematic HDTV and, I must confess, the only film that put me in such a haze I nodded off here and there. Not that the interzone between lucidity and dreaming is automatically a negative for a surreal experience. I’ve long suspected that many midnight classics benefit from an audience’s struggle to stay awake.

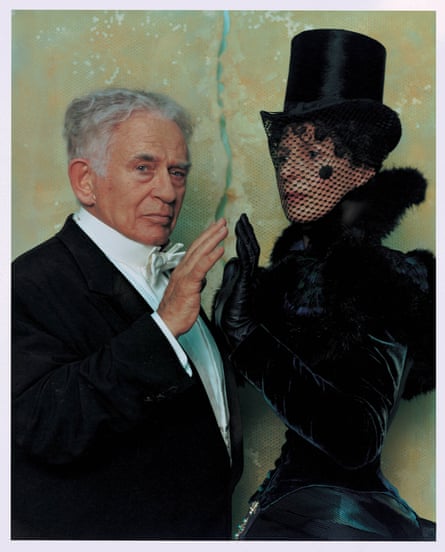

Cremaster 2’s riffs on the story of Gary Gilmore, a noted murderer who was the first American executed by the state when capital punishment was reinstated in 1976. There is a recreation of the gas station killings, plus an appearance by Norman Mailer as Harry Houdini, discussing the concept of metamorphosis. Lots of connections here. Mailer wrote a book about Gilmore called The Executioner’s Song, and there were rumours that Gilmore was an illegitimate descendent of Houdini’s. Gilmore’s mother was a lapsed Mormon. Cremaster 2 features singing by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir (again, how did this happen?) and images of bee swarms. Beekeeping is a recurring theme in Mormon lore, though I’m not so sure what elders from the Church of Latter Day Saints would make of the shots of a naked woman covered in some sort of plexiglass corset covered in bees, riding up and down on a large phallus, penetration on full display.

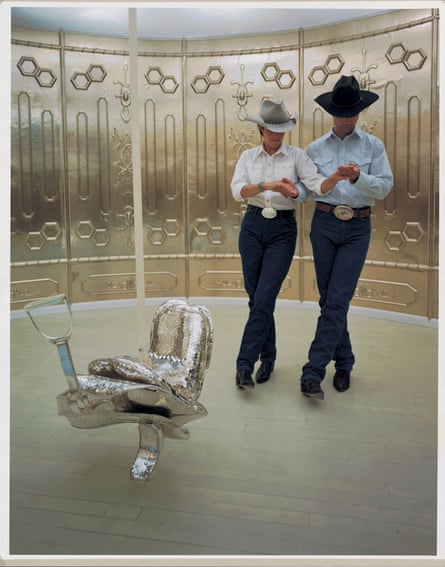

All this makes for a lot of symbols thrown into the stew that you have to figure out yourself. Some scenes are dynamic, like bees buzzing in a recording studio festooned with an Oakland Raiders patch as a heavy metal vocalist harmonises (inasmuch as one working in that idiom can harmonise). There are also some deathly dull stretches like Gilmore (played by Barney) slapping petroleum jelly around the inside a car. I don’t know what that was all about, and this was the precise moment the marathon element of this day got the best of me. There are also some striking shots of cowboys dancing, or riding on horseback with Hebrew flags. Also, some Canadian Mounties intercut with shots of mountains perfectly reflected in bodies of water, sometimes viewed vertically. Despite these bright spots, I feel like this was the most desultory entry of all.

Alex: Agreed, Cremaster 2 was hard going, although on paper this had a lot more to engage the attention – dialogue, Mailer, that hardcore porn sequence (at the end of which a bee flies out of Gary Gilmore’s father’s penis) and, my favourite part, Dave Lombardo from Slayer pelting out a drum solo and a man growling into a telephone while covered in bees. There was also Barney as Gilmore, so annoyed at being interrupted from his interminable reverie inside his car that he executes the parking lot attendant on a bathroom floor. In fact, this film even has what you could loosely call a plot – it’s a highly ritualistic retelling of Gilmore’s life and death, from his birth as a result of that sexual union to his death by firing squad, only here that’s represented by a vivid scene in which he rides a bull at a rodeo, but then both he and the beast drop dead.

Cremaster 2 sees the production values take another leap forward and there are some stunning images here, not least the camera speeding over the Columbia Ice Fields and disappearing down a crevasse at the end. Yet perhaps it’s the fact that a story seems just out of reach that makes this such a frustrating and ultimately tiring experience. Or perhaps we were just flagging four hours in.

Jordan: With that sense of exhaustion we entered the three-hour Cremaster 3, a movie which, under most circumstances, is its own endurance test. This was the film that put the whole Cycle on the map for me, when it had something akin to a traditional run in 2003. It played at Film Forum in New York and I remember seeing the name on the marquee and, not knowing what a cremaster was, wondering why they’d be showing the third part of a horror franchise.

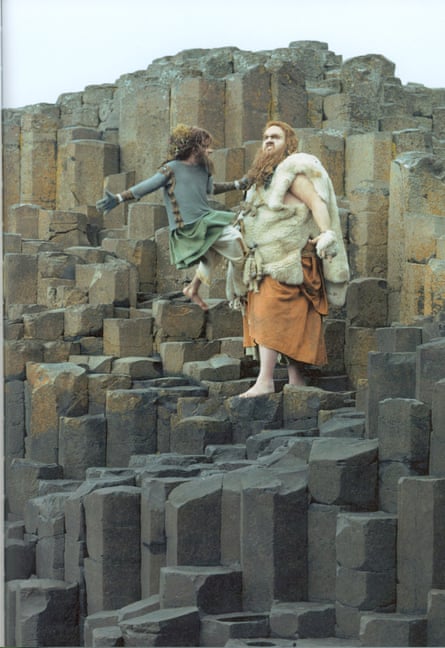

It’s a whirlwind of signifiers, again hinting at fables and true stories. We open at the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland and meet Finn MacCool, and also spend some time with Hiram Abiff (played by sculptor Richard Serra), a figure from Freemasonry that ends up being impaled through the head by the spire of the Chrysler Building.

There is a detailed recreation of the Chrysler Building’s lobby that is smashed up by autos from different eras, and the whooshing of the art deco elevator shafts are turned into musical instruments, one of my favourite bits of the entire series. (This is echoed in the more recent River of Fundament when a chorus of wheezing radiators turns symphonic.) Barney once again appears climbing up to a swank-yet-ominous bar atop the Chrysler Building where we encounter something we haven’t yet seen in the Cycle: humour.

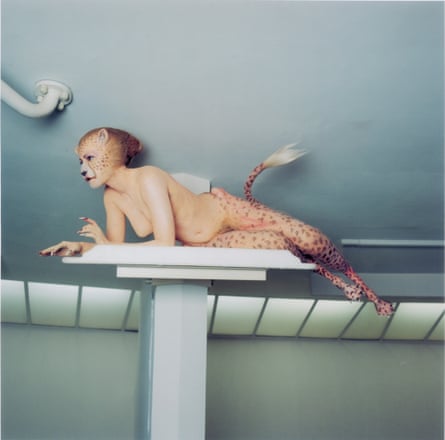

The bartender serving up frothy pints of stout runs through some Mack Sennett-like silent comedy shtick and, after hours and hours of experimental non-narrative, it goes over gangbusters. Then there are some images of a horserace leading to the most widely known section of Cremaster 3, a scramble up the rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum that involves five layers of odd tasks. These involve a kickline of half-naked women, battling Paralympian Aimee Mullins who has transformed into a cat woman, sticking enormous chess-like pieces into a crevice, surviving a mosh-pit feud between the bands Agnostic Front and Murphy’s Law and, finally, evading Serra who is slapping melted wax against pieces of steel. There’s a lot going on, frankly.

I left out the bit with the woman chopping potatoes with her shoes and the closeups of some rubber thing emerging from Barney’s anus, but apart from just being dazzled by the strangeness there is, again, the conditioning we feel to create our own narrative in our head. Cremaster 3 was shot on 24p HDTV and when converted to 35mm and projected it has made the final descent from video art to “movie”. One could walk in, glance at the screen, and not instantly know this was part of some larger scheme. I love everything up at the Chrysler’s Cloud Club and watch the curious happenings there for hours.

Alex: I thought the rubber thing emerging from Barney’s backside was his prolapsed guts after the evil Freemasons forced the compacted Chrysler Imperial (which in turn carried the corpse of Gary Gilmore, now turned into a woman) into his mouth as he sat half-naked in a dentist’s chair? Fortunately the goo from his intestines became a strange sausage-shaped life force which allowed him to get up and progress to the next stage of the cycle – the climb up the balconies of the Guggenheim in his guise of the Entered Apprentice.

Yes, Cremaster 3 had weirdness in spades. The lobby of the Chrysler building becoming the site of a violent series of car crashes and then the tower itself turning into a giant maypole; the woman cutting potatoes up with her shoes (weird shoes being another strange piece of symbolism throughout the cycle); the final sequence where the Irish giant Finn MacCool chased the Scottish giant Fingal from Ireland, throwing a rock at him which turns into the Isle of Man, taking us back to the first film, Cremaster 4; it’s so dense in symbolism that it’s impossible to see whether this is a system in its own right, or just an accretion of myths that make sense to Barney alone. Or is he just yanking our chains?

Cremaster 3 is in two distinct halves and contains an old-fashioned intermission. The first, set in the Chrysler, is as dark as its walnut interior, including a scene at a racecourse where all the horses turn out to be zombies. The second, set in the Guggenheim, is light and gorgeous to look at, as Barney clambers up the balconies dressed in full Scottish regalia, including blue argyll socks, avoiding the prowling leopard/woman and Serra with his buckets of goo, before being rebaptised/reborn in yet another bathful of sprites, these the kind of bathing beauties that took us back to the dance routines of Cremaster 1.

Afterwards, as we emerged blinking into the rotunda of the Guggenheim itself, it did feel as though reality had shifted. How did you feel after our marathon?

Jordan: What a perfect surrealist capper to this dizzying day, to exit the theatre and walk into the location of the film’s most action-packed sequence. It was difficult to find words after the stimulation onslaught but I believed I mentioned something like “Well, we truly have bragging rights.”

I’m glad to have this under my belt, but quite frankly I’m not sure the all-in-one gluttonous feast is the best way to go. You can still enter that ethereal zone watching these films in three individual sittings, which is how it is sometimes programmed. (4 and 1, 5 and 2 and then 3.) There are, eventually, diminishing returns on the attention span, not to mention a sore bottom. If I ever do anything like this again, I’m bringing a pillow.

Barney is a fascinating, commendable figure, however. People have been incorporating film into fine arts since the birth of cinema, but I can’t think of anyone who has tackled something as large scale as this. He isn’t a dilettante – he is a film director. But I don’t want him to ever “go straight”. This current push-pull between drawings, sculpture and mythology-infused storytelling is clearly working for him, and it’s remarkable, uncharted territory.

Alex: Yes, I feel as though we’d had a pretty rare experience – especially as precious few of the people there with us at 10.30am seemed to be there as we emerged over nine hours later. I felt absolutely exhausted afterwards – while I’m fairly sure I just let a lot of it wash over me, The Cremaster Cycle is challenging.

It’s a shame that there’s no easy way to see certain parts of the cycle again, as I’d definitely like to return to some of the films one day – particularly 3, the centrepiece. I guess the fact that it’s a massive, slightly macho labour is part of the concept though – lots of the work it about the will to power and the clash between nature and society – or in our case, falling asleep or leaving to go out in the sunshine versus wrapping your head around a nine-hour art film.

But I left hugely admiring the achievement – as an imaginative feat it’s stunningly dense and psychedelic, and I also admired Barney’s physical bravery. Who else would scale the Guggenheim (and it did look as though he was doing it for real) or appear to squeeze their own guts through their butthole on film? That said, after a day in the Guggenheim’s chairs, I felt as though I was quite close to doing that myself.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion