Huismes is a village built on a hillside on the fringe of the forest of Chinon, not far from the junction of the Indre with the Loire. It has no feudal castle, no Renaissance chateau, nothing to attract visitors, merely a handful of little shops and a church with a grey slate spire. Its narrow main street is often blocked by high farm carts pulled by Percherons. To the west stretch acres of vineyards which produce a fresh red Touraine wine that tastes of raspberries.

This is the chosen home of Max Ernst and his American wife Dorothea Tanning, also an artist. When he was awarded the Prix de Biennale at Venice in 1954 he bought a dilapidated farmhouse at Huismes and has spent several years in modernising it. He chose Huismes not for the soft tranquil beauty of the Loire Valley but for its remoteness from civilisation. The nearest town of Chinon is ten kilometres away and the nearest bridge over the Loire, Le Pont Boulet, is almost as far off. Yet in a fast car he can be in Paris in just over two hours. Even at 70 years of age, he has not lost his love of motoring at speed.

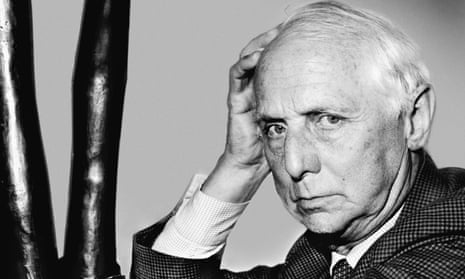

Max Ernst is still handsome and young in spirit and he still possesses the charm that made him a popular leader of international high society in the twenties and thirties. Today he prefers to live in solitude, visited occasionally by old friends such as Giacometti, the Swiss artist and sculptor, and Hans Arp, the French sculptor from Alsace, once a fellow-Dadaist, with whom he has been on close terms since 1914.

Born in Brühl, Cologne, in 1891, educated at Bonn University, Max Ernst has had three nationalities: German, American, and, since 1959, French. He has been married four times, his wives belonging to the same three nationalities: German, French and American. During the last war, after escaping from internment in

France, he was married for a few months to Peggy Guggenheim, the American art collector. With his present wife Dorothea, he lived for several years in Sedona, Arizona, in a house which he built with his own hands. After an eventful but uneasy life he has now settled in France, exchanging the stratified rocks of the Arizona desert for the meadows and market gardens of green Touraine.

When I visited him at Huismes this month, he took me into the garden to see his metal sculptures, strange figures, some with human faces, some with animal’s horns. Facing the entrance gate, almost buried among flowers, is his well-known bronze group The King Playing with the Queen – the king a seated horned creature, the queen a chess piece – which he made in America, on Long Island, in 1943.

In his studio in what was once the saddle room, he showed me some of his recent work, all abstracts. On the wall hung a large oil in tones of pale blue, the texture produced by flicking the wet paint with a triangular pad. Among the tubes of paint on the workbench I noticed a plastic doyley; he had used it no doubt as a stencil mask in a picture of a wheel in vivid orange sprayed on a yellow ground.

Max Ernst has never ceased to experiment with new and often bizarre techniques. In turn he has used collage, borrowed from the Cubists; grattage in which he grates colour on to the paint; frottage, resembling brass rubbing, which produces an exact rendering of an indented surface, e.g. a grained wooden floor block; tachage and détachage, pliage, montage, égouttage, mouillage and coulage in which he obtains streaks and drips from a loaded sponge hanging on a string above the canvas. He has formed patterns by pressing treehark and lengths of stick on to the wet paint, and many years ago he anticipated action painting.

He is known for his fantastic titles as well as for his techniques. After completion, a picture remains unnamed for several days until some chance word in conversation or some quite unrelated happening suggests a title; he does not make up a title, he waits for a title to suggest itself. The most amusing come from the Dada period when he composed pictures from medical engravings, scientific diagrams. and items cut from sales catalogues.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion