In the autumn of 1940, Man Ray met a travelling tie salesman at a party in New York. The American artist had arrived back in the US earlier that summer, having spent nearly two decades in Paris. The salesman said he was planning a cross-country trip to Los Angeles; Man Ray decided to catch a lift.

LA was an odd choice for an artist who had been a pioneering figure in the French capital, then the centre of the international art world. “Most of the surrealists who left Europe during the war came to New York,” explains Max Teicher, curator of Man Ray’s LA, a new exhibition of Man Ray’s photography taken between 1940 and 1951, at the Gagosian Beverly Hills. “Some of his best friends, [Marcel] Duchamp, [Salvador] Dalí, all went to New York. He made the very distinct decision to go to Los Angeles. He was the only one who did that.”

Quite why the artist, born Emmanuel Radnitzky in Philadelphia in 1890, spent 11 years on the west coast is unclear. The climate may have attracted him. “It was like some place in the south of France,” he later wrote, “with its palm-bordered streets and low stucco dwellings. Somewhat more prim, less rambling, but the same radiant sunshine.”

Like many European arrivals, he was struck by the popularity of motorised transport in LA, and the lack of pedestrian traffic. “I seemed to be the only one on foot, sauntering along leisurely, avoiding the more populated districts,” he observed. “One might retire here, I thought, live and work quietly – why go any farther?”

He, like other artistically inclined newcomers, such as Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg, also harboured cinematic ambitions. The only problem was, Teicher explains, “he couldn’t quite see how he could contribute. So much of the world in cinema was about working in a team, whereas when you’re working as an artist you’re much more solitary.”

Many within Hollywood, like Albert Lewin, director of The Moon and Sixpence, were keen to work with the famed surrealist, yet these offers of collaboration rarely came to much. “Man Ray was very firm,” Teicher says. “If he was going to do a film, he was going to do everything: the lighting, the set design, everything. They [Hollywood insiders] looked at him like he was crazy, because that’s not how Hollywood worked.”

Though the artist liked to present himself as a painter, he had become better known for his photography, shooting both experimental, fine-art works and commercial imagery for magazines such as Vu and Harper’s Bazaar. Man Ray had wanted to quit fashion photography following his return to the US, but he continued to shoot for publication, and, in so doing, subtly altered the way Hollywood stars were presented in the press.

“In 2018 we are so used to looking at photographs that have a sense of drama,” says Teicher, “where the sitter isn’t looking directly into the camera, and they are posing in an unusual way. Yet this was really a completely new approach that he developed. I think that is why he was so sought after as a fashion photographer: he brought art into the medium.”

It is interesting to see how Man Ray treated these subjects, just as it is intriguing to see how Man Ray, an artist we so closely associate with the wilder avant-garde circles of pre-war Paris, settled into LA.

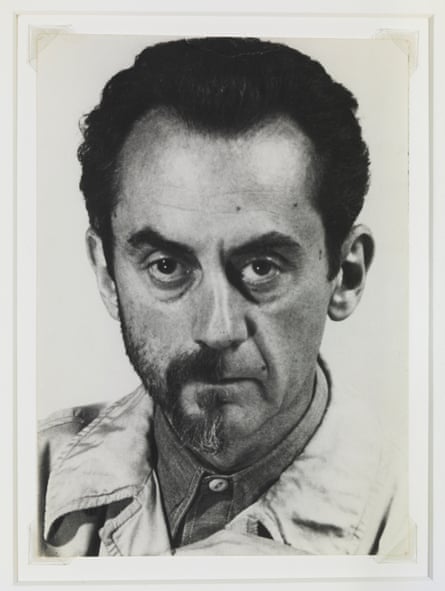

This new exhibition, the first the Gagosian has mounted with the Man Ray Trust, includes the famous image Self-Portrait with Half Beard, 1943. Man Ray is looking directly into the camera, the left side of his face clean-shaven, the right side bearded. It’s one of Teicher’s favourite images, and, as the curator explains, it appeared in suitably titled exhibition catalogue a couple of years later, To Be Continued, Unnoticed.

“In LA, art was not at the forefront of society,” Teicher says. “As a famous surrealist, he was a player in the culture of Paris, whereas in LA art was really not. He’s half there and half not. That’s his half-in, half-out approach in Los Angeles.”

Man Ray wasn’t entirely outside his old milieu. Duchamp came to visit, his friend the German painter Max Ernst had also settled out west in Arizona, and he remained in contact with the Japanese American artist, architect and LA native Isamu Noguchi. However, this exhibition demonstrates both the artist’s and the city’s limits.

Teicher has hung the photographs in four groups. The first is arranged around Man Ray’s self-portrait, the portrait of his wife, Juliet, and a few street scenes; the second is of his Hollywood circle; the third is a group of unidentified sitters, “lost to History”, Teicher says; and the final selection is his artsy friends, including Noguchi and Stravinsky. The arrangement, Teicher explains, alludes to Man Ray’s realisation that, despite surface ambitions to make it in Tinseltown, “whatever he did or wherever he went, he would always remain an artist”.

- Man Ray’s LA is on at Gagosian Beverly Hills until 17 February

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion