‘I was born with zero talent,” says Christopher Wool, ponytailed, flannel-shirted and 67. He smiles sweetly. “So I had to work at it.” We’re in Brussels, at the Xavier Hufkens gallery where the post-conceptual, postmodern, post-neo-expressionist abstract artist imbued with a punk sensibility is having a moment. Wool’s first big European survey is drawn mostly from a recent creative flowering in the Texas desert. “I was liberated by the pandemic. I could make art 12 hours a day,” he says.

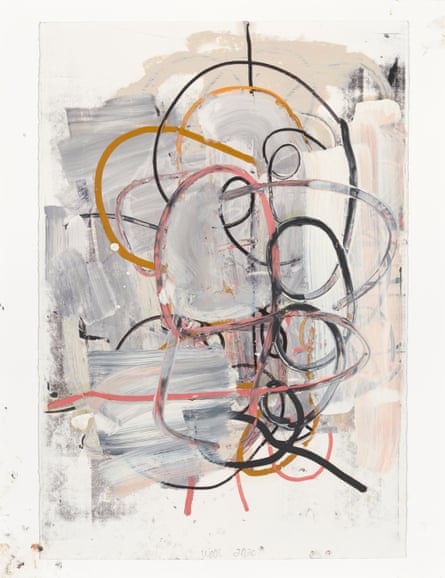

The show is a gloriously austere affair, featuring bits of twisted barbed wire, photographs of abject waste and four grand paintings made in his New York studio that initially look like redacted text. Thick layers of oil paint obscure earlier layers of work in these paintings as if, overwhelmed by anxiety and doubt, Wool sought to deface them.

Earlier this week, a visitor to the Louvre in Paris smeared cake on the Mona Lisa. Wool needs no such help: he auto-destructs his works, overpainting them to the point of obliteration. He mentions a phrase he and his wife, the painter Charline von Heyl, enjoy saying: “When you leave the studio and think you’ve had a good day, you probably haven’t.” He explains: “For me, it was never about making masterpieces. That’s what postmodernism means to me, the end of that modernist idea that the artist makes perfect works. I make a lot of mistakes but I keep them. I use them and recycle them.”

Like a hip-hop musician, he samples old material, but with one twist. The source material is increasingly his own – remaking old paintings and photos, defacing, deconstructing, or simply mucking about. “I don’t make masterpieces but I make works of art that can be strong in another way. It’s like the difference between the Beatles and the Sex Pistols. Or maybe that’s not a good comparison.”

In the Xavier Hufkens gallery, there are plinths displaying bits of barbed wire that Wool found while living in Marfa, the artists’ colony in the west Texas desert made famous by the TV adaptation of Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, which starred Kevin Bacon and Kathryn Hahn. Some he twisted into new shapes. One he blew up, with the help of an obliging foundry, into a 3-metre monumental bronze that dangles menacingly from the ceiling.

But some bits of discarded wire are simply presented as found objects, as if something chucked into the wilderness by a ranch hand was as aesthetically significant as anything moulded by the artist’s hand. Anne Pontégnie, Wool’s curator, believes there’s a sense of self-deprecation built into his work. She is right – along with anxiety, self-erasure, self-sampling and a cheery disregard for making complete masterpieces. In fact, his works are never finished: they remain open texts that he can, should he choose, deface even more.

What are not on show, though, are the acerbic text paintings that have made Wool rich and famous. His contemporaries Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer created text works satirising consumerism. Kruger: “I shop therefore I am.” Holzer: “Protect me from what I want.” But Wool’s work was more terse and enigmatic. Arranged across three decks, one read: “TROJNHORS.” Another – spread across five decks, breaking up words and echoing a line from Apocalypse Now declared: “SELL THE HOUSE SELL THE CAR SELL THE KIDS.”

Best of all, one work featured “FO” on one line and “OL” underneath. It was called Untitled (Fool) (1990). According to one critic, the piece was able to “simultaneously confront and satirise the viewer’s search for meaning”. Fool sold at Christie’s in 2014 for $14m to a private bidder who, presumably, is satirised daily by the purchase. A year later, the similarly configured Untitled (Riot) (1990) went for a staggering $29.9m.

Wool makes these auctions sound like violations: “It doesn’t just feel like you’re in a car you’re not driving,” he once said. “It feels like you’re tied up in the back and no one is even telling you where you’re going.” When I quote these words at him, he says: “I don’t remember saying that, but it sounds about right.” When he talks to me about these sales, he focuses not on the millions he pocketed, but on his annoyance that the sale of Riot meant it could not be exhibited in a show he had at the Guggenheim. “Money is not what he is about,” says Pontégnie, who has worked with Wool for 20 years. “He is in love with painting.”

Wool was raised in 1960s Chicago. “It was a fabulous place to be,” he says. His mother was a psychiatrist, his father a molecular biologist. “They were interested that I saw stuff when I was young.” Aged 11, he attended a show by The Hairy Who art collective. Later, he saw Roscoe Mitchell, frontman of iconoclastic Afrofuturist jazz combo the Art Ensemble of Chicago. Both gave him a sense of art’s subversive power.

By 1972, he was in New York. “I was young and ready to rebel against anything. The possibilities seemed endless. Everyone was creative, even if the creativity didn’t extend to more than, say, three chords. There was a DIY aesthetic that really spoke to me.” He didn’t initially want to paint. “I wanted to be a film-maker. But I realised I’m not a collaborative person.” With that typical self-deprecation, he adds: “Painting was the least adventurous thing to do. So I became a painter.”

One day, he had an epiphany while watching his landlord paint the halls of his apartment building using a roller that left a floral pattern. The glitches and misses resonated deeply with Wool. He liked how a roller or silkscreen would leave poignant traces and imperfections. He once spent hours with a photocopier feeding an image and then its copy through again and again, overlaying it with more and more lurid colours. “I’m interested in the accidents of reproduction,” he says.

While others in the Pictures Generation, such as Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince, were plundering adverts for raw material, Wool breathed new life into painting with his poetry of errors and mishaps. He cleaved towards abstract painting rendered through artificial means, building up layers to create aesthetic distance. The critic Walter Benjamin feared that the age of mechanical reproduction – photographs, records, films – would destroy the artwork’s aura. Wool seems to subvert this, using just such mechanical techniques to bring the aura back to art, something long thought to have been dead and buried.

He uses photography a lot, documenting stages of his paintings as well as creating material to sample, but he also enjoys capturing his nocturnal rambles in the footsteps of corpse-chasing photographer Weegee through the mean streets of New York. East Broadway Breakdown, a book of shots taken in the 1990s, is like Weegee without the dead bodies.

Scenes of depersonalised abjection – urban trash, views of nothing very much – echo Martha Rosler’s earlier conceptual Bowery photographs, where the street drinkers were off camera but their discarded bottles were centre stage. Wool holds up his hands and arranges his fingers to simulate a rectangular photographic frame. “Everybody takes a picture of that,” he says. Then he lowers his hands a little. “I take a picture of that.” His eye goes where others disdain to look.

At the Brussels show, Wool’s photographs of the Texas desert echo those shots he took of New York in the 90s. Using a low camera angle, he depicts not the desert’s grandeur, but its downside: rutted empty roads, a discarded bed frame, towers of tyres. What comes across is aridity, loneliness and emptiness.

Texas was nothing short of inspirational. “The openness of the landscape,” he says, “felt like it was meant for sculpture.” Indeed, being in Marfa changed how he worked. “I started to sculpt but, being new to sculpture, I don’t know how to do it.” There’s that self-deprecation again, that sense of having zero talent and having to overcome it. Wool smiles and adds: “I work at it.”