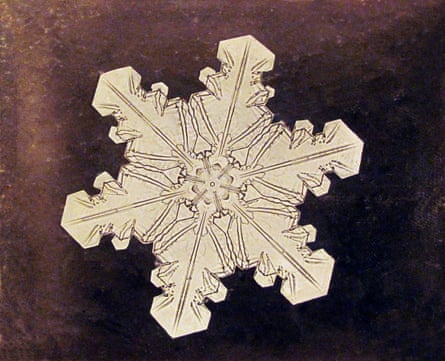

The structure of a snowflake is one of the most beautiful things in nature. Every flake is different, they say; each one an intricate lattice of frozen water molecules with spectacular symmetry. Everybody knows this. When children make paper snowflakes they cut them out to mirror this crystal magic.

But no one knows any of this intuitively. To the naked eye, snowflakes are just white dots. The universal image of them as wondrous crystalline formations is a product of microscopes, photography– and one man in Jericho, Vermont.

He is remembered as Snowflake Bentley or The Snowflake Man. Today his original photographs are treasures of the Smithsonian Museum and his glorious discovery shapes the way we imagine. Yet for much of his lifetime, Wilson A Bentley was dismissed as an oddball.

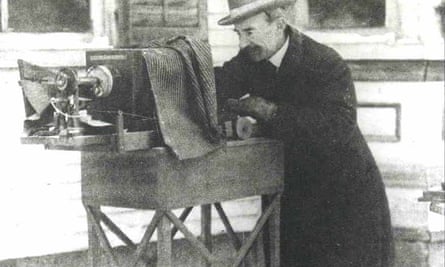

Born in 1865, Bentley spent his whole life in rural Vermont, where he worked on his family’s farm. He was given a microscope for his 15th birthday. The most amazing things he could see with it were snowflakes – and there were plenty to look at in Jericho, which gets up to 200 inches of snow every year. Bentley noticed how different each one seemed and set out to do something no one had done before: photograph these tiny wonders.

He acquired a camera at 19, and set about exploring the possibilities of photomicrography – shooting things too small to be seen by the naked eye.

Modern cameras can record microscopic marvels from insect eyes to plankton. But Bentley started his experiments in the first century of photography, when the form was in its infancy. Henry Fox Talbot, a British scientist and pioneer of the artform, called photography “the pencil of nature”. There could hardly be a more perfect image of this than Bentley’s pictures of snowflakes.

In fact, long before photography, scientists saw the artistic possibilities of the microscope, which was invented in the 17th century, and illustrated what they saw. At first, Bentley tried to draw the flakes, but was frustrated that he couldn’t get them right. So he invented a way to rig his camera up to his microscope. It took years to get right. Capturing snowflakes and getting them under the microscope wasn’t easy, either: he caught them on a feather or a tray covered with chilled velvet. The microscope slide also had to be chilled, and transferring the snowflake on to it was an extremely delicate business involving tiny wood chips and turkey feathers.

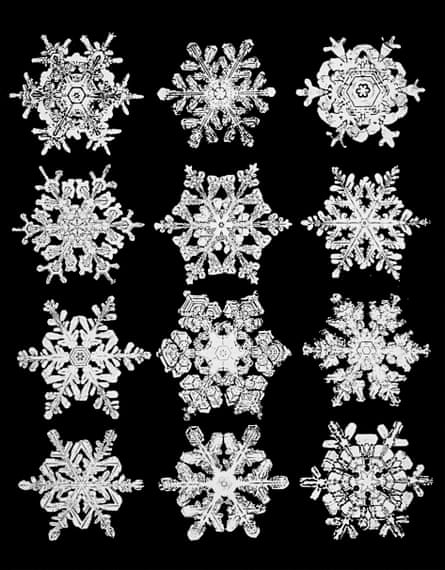

The results are astonishing. Bentley photographed his snowflakes against light, then laboriously gave the prints a black background in a process that involved scraping and rephotographing his plates. Today, the 5,000-plus pictures he took are still beguiling. They are miracles of art as well as science.

Bentley published scientific articles and magazine pieces on the beauty of snowflakes, and some scientists at the time recognised his achievement. Yet his outsider status as a farmer delayed acceptance of his most important discovery. For after photographing thousands of snowflakes and studying them, Bentley came to the conclusion that every child today knows: each snowflake is unique. At last, a year before his death, he published this insight in the book Snow Crystals, written with physicist William J Humphreys and reproducing 2,300 of his photographs as evidence.

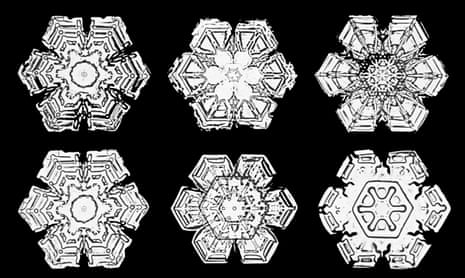

The Snowflake Man’s discovery, however, is not completely accurate, according to modern chemists. Rather than every snowflake being utterly unique, it has now been proved that each falls into one of 35 basic patterns. This is because snowflakes are natural crystals, and crystals obey laws of symmetry and mathematics. They are not divine miracles, but natural wonders. And Snowflake Bentley taught us to see them.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion