You can't con an honest man, said Phineas T Barnum, and maybe you can't hoax a publishing company that doesn't want to be hoaxed, or that doesn't see the financial advantage in not being too uptight about the difference between truth and falsehood. Lasse Hallstrom's entertaining new film on this subject is a fictionalised account of one of the last century's wackiest literary scams - though flawed, because it's based on the unreliable scamster's own self-serving account of the matter, published after he was released from prison.

In 1971, struggling novelist Clifford Irving, whose only success to date had been a non-fiction study of art forgery, claimed to have been selected by reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes to ghostwrite his autobiography. Hughes allegedly communicated with him only in mysterious but authentic-seeming handwritten scrawls, which Irving produced at meetings. Bamboozled by Irving's brazen and plausible manner, the mighty McGraw-Hill publishing company and Life magazine handed over seven-figure cheques to this extraordinary man, whose wife cashed them in a Swiss bank account with the aid of a false passport in the name of HR Hughes. In this film version, the crunch comes when the panicky publishers demand some sort of proof that the whole thing is for real. Irving ups the ante by claiming that Mr Hughes himself will be shortly touching down in his private helicopter on the roof of the McGraw-Hill building in midtown New York to discuss the matter in person.

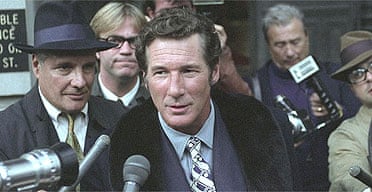

Richard Gere is good casting as the trickster, a desperate writer facing career death in middle age, and crucified with rage and envy at younger authors getting the money and acclaim he considers rightfully his. When he gets the brainwave about the Howard Hughes fake, he is hugely complacent, yet secretly mortified at what it means: a definitive abandonment of any dream he has of being the next Roth or Mailer. The only way to suppress his climbing panic and self-hate is to continue to bluff it out. Like a crazed method actor, he learns to face down sceptical executives with the brash negotiating style of his imaginary best friend, Hughes. It was a sociopathic high-wire act. With the help of his put-upon buddy Dick Suskind, a sweaty and terrified individual played by Alfred Molina, he sets about amassing genuine research and purloining documents that would make his yarn look real.

This Laurel and Hardy duo are even shown blagging their way into the Pentagon by claiming to be Hughes employees and pinching top-secret files; could this really have happened? Perhaps, in 1971, it could. However, a scene showing one sneaking out and photocopying a 500-page document in about half an hour doesn't ring true. Hope Davis is the McGraw-Hill executive who is in a permanent agony of doubt at having brought this snake-oil salesman on board, and John Carter plays publisher Harold McGraw, a figure who was to become hardly less legendary in his own organisation than Hughes was all over America. Marcia Gay Harden, one of Hollywood's least-known Oscar winners, plays Irving's watchful wife, a would-be painter: casting that may have been inspired by her award-winning performance as Jackson Pollock's lover in the Ed Harris biopic.

The obvious comparison is with the Hitler diaries in 1983, although that was massively more shaming in that those actually made it into print. As in the Hitler case, the combination of book publishing and journalism, with a high-stakes serialisation deal, is what's so explosive. The tight deadlines and frantic fear of being scooped result in a cynical, willed gullibility about a property that is probably faulty, but has passed too far up the corporate approval chain to be recalled.

But the Hitler diaries were convincing at first for much the same reason that Irving's bizarre Hughes story initially passed scrutiny: the simple bulk of the manuscript. The sheer size of the text - plausible, internally consistent - was powerfully convincing in each case. If you have the fanatical dedication and warped imagination to produce something so substantial, then the fake will be very effective. And Irving emerges from this film as a man who can see that in an age when reputation and perception are so important, the gulf between the real thing and a good-looking forgery can be very narrow indeed. Cases like these are a sobering reminder that society rubs along because the vast majority of people tell the truth, and believe others are telling the truth. When someone comes along with enough Nietzschean chutzpah to lie and to go on lying, it is worrying how far he can get.

The movie is weaker on Irving's extra-marital affair with the actress Nina van Pallandt (a small and unsatisfying role for Julie Delpy) and also in its insistence on a Nixon/Hughes-conspiracy dimension, which is there to lend an unexpected sort of credibility to Irving's story, a sense that he isn't simply a contemptible vendor of porky pies. As portrayed in the movie, it's a conspiracy that may or may not exist wholly in Irving's frazzled brain. Like George Clooney's 2002 movie Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, about the game show impresario and notorious fantasist Chuck Barris - who claimed to have been recruited by the CIA - the movie isn't entirely clear about whether it's taking Irving's conspiracy claims at face value. It adds touches that suggest he's imagining it, but other scenes hedge the bets by suggesting there is something in the conspiracy after all. These objections aside, it's an elegant, entertaining parable of the emperor's new clothes.