Next week the players who represented Brazil at this year's World Cup will go on holiday and remember being successes. Born poor boys in most cases, they have become, in every case, extremely rich and envied men. None was universally liked before Tuesday – no footballer quite transcends his tribe – but they could count on the affection of a few million people at least, which is a few million more than most of us can say. And all those millions required was to watch them do their best. Victory could be dreamed of, but everybody knew it would be hard to realise without Neymar or Thiago Silva. As it turned out, the world, Brazil and the players themselves all discovered that their worst was worse than expected.

So next week, on their private beaches, the players will wonder what kind of punishment awaits a Brazilian who has exposed his nation to ridicule and ignominy on a day when the world had gathered to watch them showing off. And the worst thing is, straight after wondering, they'll know.

On the morning of 16 July 1950, Moacir Barbosa was a success, too. As Brazil's goalkeeper, he was a reigning South American champion, having won the Copa América the previous year, beating Paraguay 7-0 in the final. (And that nil matters. Ask any goalkeeper.) He'd been a multiple champion with his club, too. That day he would represent his country again, this time in the first postwar World Cup final at the newly built Maracanã stadium in Rio. Around 200,000 people, the largest crowd in football history, expected Brazil to beat Uruguay easily, despite needing only a draw to win their first world title, and Brazil scored first, but finally lost 2-1.

It was absurd to vilify Barbosa. He was not at fault for Uruguay's first goal, one of those wallops into the top corner that all keepers have to watch now and then. For the second, he let a shot through at the near post, a classic error, certainly, but one you'll find scattered throughout even the most glorious careers. Besides, Barbosa was voted the best goalkeeper in the tournament by journalists covering it, and was far from the only player who disappointed on the day.

There was a vacancy for a scapegoat, however, and after being at first included on a shortlist of Barbosa, Juvenal and Bigode – Brazil's three black players – Barbosa got the job. For weeks after the match, he and his wife Clotilde dared not leave their home in north Rio, nor even answer the phone. They moved in with friends. Fellow pros accepted what happened to Barbosa could happen to them, and he continued to play, but only once more for Brazil. It would be 40 years before the country picked its next black goalkeeper.

And the vilification of Barbosa was never corrected. Even as the Brazil team began to earn a reputation for both beauty and winning, Barbosa remained toxic for many Brazilians. "He is the man that made all of Brazil cry," he once overheard a woman whisper to her young son in a supermarket. During preparations for the 1994 World Cup he visited the national team's training camp to meet the players, but was turned away as a bad luck charm. (Brazil won the tournament on penalties, thanks to good luck, and a crucial save from their white goalkeeper Taffarel.) Throughout his life, Barbosa tried to remain good-humoured, even when it was hard to find people who would laugh. The maximum sentence in Brazil was supposed to be 30 years, he used to say, and died penniless in 2000, still saying it.

Already there is a feeling about this litter of scapegoats that they've been bred not to exorcise Barbosa's ghost, but to replace him. "It is a scar which will remain with us for the rest of our lives," said the striker, Fred, a leading candidate on the 2014 shortlist, who may well never play for Brazil again."We will never be able to find the words to explain this situation," said Fernandinho, one of the leading culprits in midfield. "I'm not sure how long it will take for me to get over this." They know they must prepare for something permanent.

So what is the answer? Like Barbosa, the Scottish goalkeeper Frank Haffey hoped that humour might rescue him from his own disgrace, but it is hard to argue that it worked. In 1960 Haffey played his first game for Scotland, saving a Bobby Charlton penalty in a 1-1 draw at Hampden Park. On 15 April 1961, he played his last, at Wembley, where Scotland suffered what remains their heaviest ever defeat to England, 9-3. Haffey made mistakes. The whole team did, and they admitted it. Yet being the Scot who let England score nine times cannot be brushed aside.

After the game Haffey remembers being photographed beneath clocks showing three minutes past nine, or at platform nine in train stations. "Half-past Haffey" became a joke back home. He remained Celtic's goalkeeper – a major honour – but the way Haffey tells it, Celtic soon started looking for a reason to get rid of him. He was dropped from the first team after a mild ankle injury in 1963, and remembers noticing that his name was soon replaced in the lyrics of the Celtic song. "I'd been out of the first team just three weeks before the record came out," he told the Sunday Times in 2003. "'There's Haffey, Young and Gemmell, they proudly wear the green,' became 'There's Fallon, Young and Gemmell.'"

When Celtic cut his wages, he left for Swindon. Then in 1965, not liking Swindon, he and his wife emigrated to Australia, where he played for five more years, far below his previous level. Afterwards he became a coach and, naturally, a singer and comedian. "I have to say that if I had been wearing these glasses that day against England," he told the Daily Record in 2005, "then I swear they would only have scored about eight."

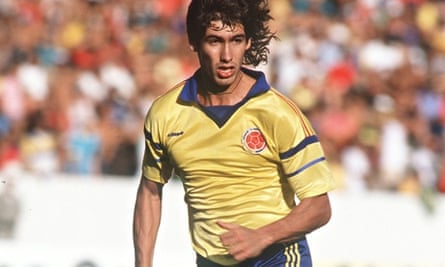

For others, failure has been horribly serious. In 1994, Colombia's best-ever team travelled to the World Cup in the US, leaving behind a country in chaos following the murder of the drug baron Pablo Escobar. After the first game, a defeat to Romania, they began getting death threats – including, mysteriously, on the TV screens in their hotel rooms. The second game they lost to the hosts, in part because of an unlucky own goal scored by the captain Andrés Escobar (no relation). In stretching to intercept a cross, Escobar accidentally nudged the ball into his own net, the first own goal he'd ever scored.

Twelve days later, the team by then eliminated, Escobar was shot six times and bled to death outside a nightclub in Medellín. Precisely what happened and why will probably never be known, although a local gangster's bodyguard Humberto Castro Muñoz confessed to the murder, and served 11 years in prison for it. Escobar was 27 when he died. He had had no involvement in the drug trade, had just got engaged, and was about to sign for AC Milan. It seems that he was heckled by a group of men about his goal, and argued back.

Had he lived, Escobar might yet have won Colombia over. Sins committed on the pitch are best redeemed there, too. Perhaps the greatest example is a player you may have heard about. "No Englishman, or Englishwoman, will need reminding of that moment," read a profile of David Beckham after his disgrace in 1998, but today I suspect some will. Today Beckham is a virtual aristocrat, a figure of global goodwill, whose presence gilds any big event. It takes some effort now to recall the bilious mood in England when he was just, in the Mirror's headline, "one stupid boy".

Beckham's crime, if you do need reminding, was to give Diego Simeone a light flick on the calf in retaliation for being flattened during a World Cup game with Argentina. The referee was entitled to send him off, and did, and England lost, on penalties. Beckham was "terribly affected by it", according to Bobby Charlton, one of many football grandees who pleaded clemency for him, much as they plead it for the Brazil team now. But it made no difference. With his sarong, his floppy hair and his pop star girlfriend, the boy Beckham had always been as much an enemy of "English" football as its hero. There were death threats and denunciations. An effigy of him was strung up outside a pub in London because, as the landlord put it: "He needs teaching a lesson."

In fact, Beckham taught England something. The following season he played brilliantly, and won the treble with Manchester United, an unmatched achievement in English football. In 2001, his last-minute free kick against Greece gave England a place at the 2002 World Cup and, when there, the team beat Argentina thanks to a Beckham penalty.

The 2014 World Cup offers another story of hope, albeit in contrast to Beckham's, because Luis Suárez is guilty of essentially the same offence. One of his country's star players, he played brilliantly until a moment's indiscipline got him excluded from the rest of the tournament, and without him, Uruguay lost. Yet there have been no Suárez effigies in Montevideo. Indeed, his status there seems to have risen beyond heroism into something more like martyrdom, and now he's got his dream move to Barcelona. The mood of victimhood in Uruguay, it seems, protected him, and there was a similar mood in Brazil after Neymar's injury. If the team had managed even a narrow defeat to Germany, they might have escaped with soothing excuses. Perhaps excuses were what they went into the game looking for.

Either way, if there is a time to feel sorry for footballers, it isn't now, when the world is glaring at them, but later. And that goes for all players, even those who escape without a catastrophe in their careers. Claus Lundekvam was one. In 15 years as a footballer, from 1993 to 2008, he never won anything. He played 40 times for Norway, but never at a big tournament. He is remembered, if he is remembered, by Southampton fans as a dependable but unexciting centre-half. But when his career ended, he fell apart.

Even at Lundekvam's level, somewhere in football's upper-middle class, the money and the fame and the membership of high society are automatic. And when you retire, so is the withdrawal. Lundekvam quickly became a heavy drinker and drug-taker, and then an addict. "I think I was looking for something to replace the adrenaline rush, the buzz you get, that feeling of really being alive," he says. "You get used to performing in front of thousands every week and when that's gone, then suddenly there's a huge mental void that becomes almost impossible to fill."

His wife left him, taking the children, and at that point he gave up. "I accepted," he says, "that as a human being I was finished." As it turned out, just before the addictions did finish him, he changed his mind, went into rehab, and lived to tell this tale. Yet Lundekvam believes that many other ex-pros go through something similar. Former and fading players such as Gary Speed, Agostino Di Bartolomei, Hughie Ferguson and Abdón Porte disgraced no one in their careers, but took their own lives for reasons that will never be explained. It will be little comfort to the Brazil team on their holidays, but perhaps the shame of football isn't the hardest thing to live with. It's the glory.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion