Luis Suárez is squinting into the Spanish midday sun. We are sitting by the side of a pitch at Barcelona’s training ground, and he is talking movingly about his relationship with his wife, Sofi, the humility of his new team-mates at Barcelona, the Monopoly games he enjoyed with the players back at Liverpool. And the more he talks, the more I’m thinking, can this be the same man who sank his fangs into Giorgio Chiellini at the World Cup? He speaks quietly, with a sweet if monotonous intensity, and still there’s this nagging question.

Eventually it just blurts out. “Do you think there’s something wrong with you?” I ask. Even I am surprised by my abruptness.

He looks at a loss. “I don’t know,” he says. “I don’t really know what I can say to that.”

Well, I say, you seem like a good man – kind, decent, shy, and yet when you’re on the pitch, you’re an animal. “I think the people who really know who Luis is are the people who are by my side, who have always been by my side.” He speaks about himself in the third person, as if somehow he is not fully answerable for the footballer Luis Suárez. “Of course, people will always judge you by your attitude on the pitch, judge you on things that have happened in your past. I have been through a tough time. I always say, in all honesty, that the Luis on the pitch is nothing like the Luis off the pitch.”

Has any other footballer packed so much controversy into what is still half a career? The bites, the bans, the diving, the 2011 suspension for racially abusing Patrice Evra, the handball off the line in the 2010 World Cup quarter final – it’s hard to know where to start. For me, one image dominates: it came at the end of a match this May, one that Liverpool had to win to have a realistic chance of securing their first league title in 24 years. They had been leading 3-0 and went forward, looking for more goals to reduce Manchester City’s superior goal difference. But every time they did, Palace broke away and scored. The match ended 3-3, and Suárez was in tears, beyond comfort. He pulled his shirt over his head so the fans couldn’t see, and had to be led off, blind and wretched, by his team-mate Kolo Touré.

It looked like an extreme end to an extreme season: despite having been suspended for the first five matches (for biting Branislav Ivanovic), he finished top scorer in the Premier League – an astonishing 31 goals in 33 games. But the best and worst was yet to come. After missing the opening game of the Brazil World Cup while recovering from knee surgery, he returned against England to beat them single-handedly with two goals. Then came that final group game against Italy. Suárez, desperate to see Uruguay through, again tried to win the game single-handedly. But nothing was going his way, and in the 80th minute he took it out on Chiellini’s shoulder. Gnash. Suárez threw his hands to his teeth and went down as if he’d been punched. Somehow this bite was even more shocking than the previous two: he was representing his country in front of the world, and seemed to have learned nothing. The referee missed the incident, but Fifa reacted ferociously – with a four-month ban from football-related activity (meaning he couldn’t even train), later reduced to a four-month ban from football.

This would have done for most players, but not Suárez. The first time he bit a player (PSV Eindhoven’s Otman Bakkal, in 2010), he followed up with a lucrative move to Liverpool. The second time, he responded by equalling the record for goals scored in a single Premier League season (31, up with Alan Shearer and Cristiano Ronaldo). This time, he secured himself a stonking £65m transfer to Barcelona, arguably the world’s most successful football club. He is likely to make his Barcelona debut tonight – against Real Madrid, a match between the two Spanish giants known as El Clasico. As the Liverpool chant used to go, there’s only one Luis Suárez…

On Monday morning, the day before Barcelona’s Champions League match against Suárez’s old club Ajax, the Uruguayan is warming up at the club’s state-of-the-art training ground. Scores of cameras click and whir as the squad play their tiki-taka version of piggy in the middle. There’s Messi and Neymar pinging the ball to each other along the ground, in true Barcelona style. Here’s Iniesta and Alves and Mascherano. Ping, ping, ping. It’s a lovely, collegiate kickaround. And at the centre of the action is Suárez, already more vocal, more demonstrative, more physical than most of his colleagues. Even in a training session, for the benefit of the press, he holds out his hands in disgust when he doesn’t receive a ball, loudly claps a good pass, barges into a team-mate to collect the ball. He doesn’t do anything by half.

That includes his new autobiography, Crossing The Line. The first chapter is devoted to biting, the third chapter is titled The Hand Of Suarez, and the fifth is simply called Racist. It’s a revealing and surprising book, not least in its depiction of his relationship with Sofi – the couple have been together since he was 15 and she was 13.

Like most of today’s great forwards, Suárez is a supreme physical specimen. He has the balance of a ballerina and the thighs of a weightlifter. He is a true predator, but while most predators operate within the penalty area, he can swoop from the halfway line. He still plays football like a child – always keen to shoot and try a new trick, quick off the mark, selfish, as goalscorers have to be. He is also one of the game’s great chasers, constantly harrying defenders.

Last week, he received the Golden Shoe for 2013/14, awarded to the leading scorer from the top division of every European national league. Now he says his job is to help win La Liga for Barcelona. Although the relatively impoverished Atlético Madrid won Spain’s top league last season, the past couple of years has seen an arms race between Barcelona and Real Madrid as they have stockpiled global superstars. So the signing of Neymar by Barcelona was matched by the signing of Gareth Bale for Real Madrid last year; and Suárez’s signing has been matched by World Cup top scorer James Rodríguez’s move to Madrid. But Barcelona’s outrageous South American attack – Brazilian Neymar, Argentinian Messi, Uruguayan Suárez – could be the greatest yet in club football.

In a way, Suárez says, signing for Barcelona is like coming home. He grew up wanting to play for the club, and Sofi’s family lives here. You can see the little boy in him when he talks about his new job. “I still can’t believe it, it still hasn’t sunk in.” He pauses. “After everything that happened, the various difficult situations, what I need to do now is enjoy things – because I have got to where I want to be.”

It seems bizarre to talk about last-chance saloons for a player who has just enjoyed a season like his last, and yet for Suárez this is the opportunity to prove himself as one of the true footballing greats – to prove that he will be remembered more for his artistry than his antics. For all his achievements, he has never stayed at a club longer than three years.

Is he worried that he won’t get into the team, with Messi and Neymar already ahead of him? No, he says, he’s looking forward to them all playing together. “They are players of such high quality that they can adapt to any new player. The only thing I need to do now is adapt myself, not just to them but the whole team. I need to watch them and learn from them. They are making me feel comfortable.” The word Suárez returns to again and again is humble – whether it’s his own background, his attitude towards his team-mates, his lack of education, his desire to be a good family man.

Suárez was born in the town of Salto 27 years ago (one of his nicknames is El Salta; the other is Grumpy) and left for the capital Montevideo at the age of seven. His father, a former soldier, took work where he could find it – in a biscuit factory, as a concierge; his mother worked as a cleaner at the local bus station. They split up when Luis was nine. He describes his upbringing as “anarchic”, and the young Suárez spent much of his time on the streets – playing football or just hanging around with friends and drinking mate, a South American herbal tea, drunk through a silver straw. And apart from family, his life is still very much about mate and football.

He signed for Montevideo’s major football club, Nacional, at 14, but he was overweight, on a kill-me-quick diet, and insists there were many players with more natural skill. What he did have was attitude – a hatred, even a fear, of losing. At the age of 15, he ran 50 yards to argue with a referee and ended up head-butting him. (“The referee had a broken nose and was bleeding like a cow,” the technical director of Nacional, Daniel Enriquez, has said.) Nacional wanted to let him go because he was spending too much time on the town, and had scored only eight goals in 37 matches.

Then he met Sofi. Her father was a banker, and she lived in well-to-do Solymar, just outside Montevideo. When her father’s bank shut down a year later, the family moved to Barcelona and Suárez was distraught. When the Dutch side Groningen scouted him three years later, he moved to Holland because he thought at least he’d be close to Sofi; one weekend she came to stay and never left.

After Groningen, he captained Ajax. There, he scored 81 goals in 110 appearances and barely put a foot wrong – until he bit Otman Bakkal on the shoulder in November 2010. For that, he received a seven-match ban and was labelled “the cannibal of Ajax”. Two months later, he signed for Liverpool, for what turned out to be a bargain £22.8m. His goalscoring record was almost as impressive in England’s tougher Premier League, and he didn’t tuck into another player until April 2013, when he bit Chelsea’s Branislav Ivanovic on the upper arm. The referee missed the bite and Suárez went on to score an equaliser in injury time; he was subsequently banned for 10 games.

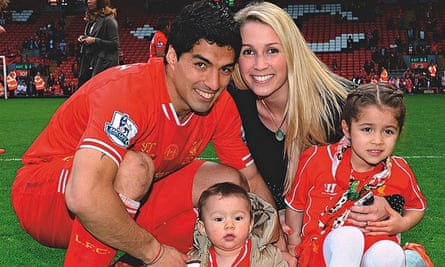

The constant through Suárez’s highs and lows has been Sofi. There is something incredibly tender and unmacho in the way he talks about her and their two children; in fact, Suárez has a notably unmacho side. He has pictures of Sofi and the children on his mate bottle and his scruffy washbag, and the word Sofi elegantly tattooed on to his wedding finger; the children’s names, Delfina and Benjamin, are tattooed on his wrist. When he scores, he kisses each tattoo. Why doesn’t he have a more conventional footballer’s tattooed sleeve? He says he can’t be doing with that kind of nonsense.

Like all elite footballers, Suárez, who earns £200,000 a week, is surrounded by yes-men. Sofi is the one critic he will listen to. “She was there at the beginning of my career – she supported me when I was a nobody. She put her trust in me, helped me with my studies, with work. When we started living together in Holland, we started getting older and things started getting more serious. We always wanted to start a family. We are aware that, for a famous footballer, it is difficult to have someone by your side in this way. That is why I really value it.”

It’s unusual to hear a footballer talk about his partner so lovingly. “Well, Sofi means everything. She means the start of my career, she means a change of countries and lifestyles. She’s been there all the time, through good and bad.” Would he have succeeded without her? “I don’t know. I know that the person on the pitch is me, but the person off the pitch, who lives life in the right way, with good rest, good diet, this comes from the person you have by your side. Without her, it would have been difficult.”

Look, I say, I’m confused. How can such a gentle man become so feral on the pitch? Now it’s his turn to look confused, and he struggles to answer. He says that he gets so stressed, so hyper, he just needs a release, however irrational. He is also terrified that if he subdues these instincts on the pitch, he will lose his hunger. Did he feel disappointment or shame after he bit Chiellini? “Of course. I felt disappointed in myself, for my wife, my children, and particularly for all the Uruguayan people, and when something like that happens, the most important thing is to accept what you’ve done wrong and to apologise. When you feel you’ve done something wrong, you should apologise for it.” He later tweeted an apology to Chiellini from Montevideo.

What did Sofi say? He doesn’t reply, so I try to make light of it. “Did she say, ‘Oh for God’s sake, not again, Luis!’” But his answers have become morose. “The truth is, I don’t really remember what she said. I had no desire, no will to speak to anybody.”

Because you were so upset with yourself?

“Of course.”

I tell him I have an autistic friend who bites when he feels he’s losing control. Does he think he could be on the autistic spectrum? “No, it doesn’t make me think that. Everyone has different ways of defending themselves. In my case, the pressure and tension came out in that way. There are other players who react by breaking someone’s leg, or smashing someone’s nose across their face. What happened with Chiellini is seen as worse. I understand why biting is seen so badly.”

It’s interesting that the three times he has bitten people, he has never taken a lump out of anyone – as Mike Tyson did from Evander Holyfield’s ear. So even though it’s an act of wrecklessness there is some control? “Yes, it is like an impulse, like a reaction. Almost as if you realise straight away…”

And you pull back?

He nods, almost enthusiastically. He has sought help for his biting, and I ask what advice his therapist has given him. “They are personal issues, private issues, which I won’t make public now or ever in the future.” He is biting his nails, looking at the floor. Is his biting in the past? “Yes, I think all the bad things I have been through are in the past. I believe I am on the right path now, dealing with the people who can help me, the right kind of people.”

He looks desperate to get away, so I change the subject. In his book, he is very warm about his former Liverpool team-mates – Steven Gerrard’s inspiration and fatherly advice, Glen Johnson’s banter with him in Spanish, Daniel Sturridge’s talent (“The best partner I’ve had in my career”), playing Monopoly with Lucas Leiva.

Did he ever knock over the board if he was losing? He grins. “No, no. I got angry, but not that.”

I ask if we can have a kickabout on the pitch. Again, he is gentle and obliging. We do a few keepy-uppies. “Would I make the Barcelona veterans’ Z team?” I ask. He says I’ve got “not-bad technique” and I tell him he’s made my life. We continue to chat while kicking the ball to each other. One of the most compelling chapters in his book comes when he talks about the occasion Manchester United’s Patrice Evra accused him of racism, after a match in 2011. It emerged that nobody else had heard anything, but Suárez eventually admitted to having called him “negro” once; he was suspended for eight games. His defence was, and remains, that negro simply means black in Spanish, and is acceptable in his culture – like calling somebody chubby or skinny. I believe him when he says he’s not a racist, but I don’t believe him when he says it wasn’t meant as an insult. After all, they were rowing at the time.

He says he can accept being criticised for biting and diving (though he does point out he’s only been booked twice for diving), but he cannot accept the racist allegation, and insists he will never speak to Evra again; he refused to shake his hand before a game after completing his ban. I ask why he thinks it’s so much worse to be labelled a racist. “I know I was wrong with the biting and the diving, but I was accused of racism without any proof. There were lots of cameras, but no evidence. It hurts me the most that it was my word against theirs.” But surely that’s irrelevant – he himself admitted he used the word, as he does again today. “Every culture has its way of expressing itself, and that’s a word people in Uruguay use all the time, whether somebody’s black or not black. It gets used a lot without those connotations, and that’s why it is completely different from how it is expressed in England, no?”

Did he mean to insult Evra, just not in a racist way?

“No, not at any time. I just said, ‘Why, negro?’ and it was just like asking ‘Why?’ These are things that footballers say, that happen all the time.”

We’ve finished playing keepy-uppies. I lean on Suárez’s shoulder and tell him I’m knackered. I am genuinely touched by his relationship with Sofi and would love him to see out the rest of his career at Barcelona, as the non-diving, non-racist, non-biting world-beater he probably is at heart. Although it is obvious he hates talking about biting and race, he must realise that when he does, people are more likely to regard him as a reformed character. And it feels to me that we have got on well.

It turns out I have misjudged the situation. Suárez does not feel the same way and abruptly decides to terminate the interview. Sweet Suárez has been replaced by Stroppy Suárez. But there’s so much left to talk about, I protest: we were meant to be hanging out for longer. We’ve not had time to re-enact that first Liverpool goal against Norwich, let alone discussed his ambition to be a goalkeeper. But Suárez has had enough. He has to collect his daughter, he says. He raises his eyes to his agent, and off they go. The microphone he is wearing for filming is still on, and we can hear him complaining.

“Calm down, man, you’re getting flustered,” the agent says.

“They are asking me again about the biting. They have asked me about the bite 38,000 times. Never again, never again, I swear never again, this is the last time.”

I watch him squeeze into his Audi sports car, and he is off. We’ll wait for him to come back, I tell his agent, hopefully. Don’t bother, he says. “Nobody tells Luis Suárez what to do.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion