Patti smith & robert maPPlethorPe - Christopher Bollen

Patti smith & robert maPPlethorPe - Christopher Bollen

Patti smith & robert maPPlethorPe - Christopher Bollen

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

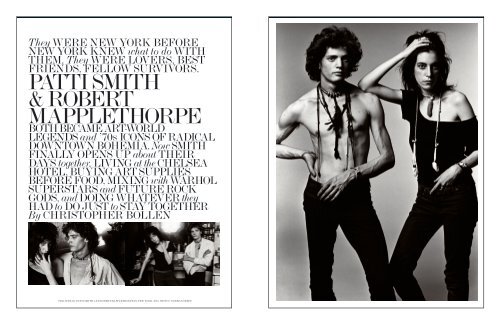

They were new york before<br />

new york knew what to do with<br />

them. They were lovers, best<br />

friends, fellow survivors.<br />

<strong>Patti</strong> <strong>smith</strong><br />

& <strong>robert</strong><br />

<strong>maPPlethorPe</strong><br />

both became art-world<br />

legends and ’70s icons of radical<br />

downtown bohemia. Now <strong>smith</strong><br />

finally oPens uP about their<br />

days together, living at the chelsea<br />

hotel, buying art suPPlies<br />

before food, mixing with warhol<br />

suPerstars and future rock<br />

gods, and doing whatever they<br />

had to do just to stay together<br />

By christoPher bollen<br />

This spread: <strong>Patti</strong> Smith and RobeRt maPPlethoRPe in new YoRk, 1970. phoTos: noRman Seeff.

96<br />

In 1967, <strong>Patti</strong> Smith moved to New York City from<br />

South Jersey, and the rest is epic history. There are<br />

the photographs, the iconic made-for-record-cover<br />

black-and-whites shot by Smith’s lover, soul mate, and<br />

co-conspirator in survival, Robert Mapplethorpe.<br />

Then there are the photographs taken of them<br />

together, both with wild hair and cloaked in homemade<br />

amulets, hanging out in the glamorous poverty<br />

of the Chelsea Hotel. It is nearly impossible to navigate<br />

the social and artistic history of late ’60s and ’70s<br />

New York without coming across Smith. She was, as<br />

she still is, a poet, an artist, a rock star, and a bit of a<br />

shaman. But it is her friendship with Mapplethorpe<br />

where her legend begins—and like most beginnings,<br />

this one has been romanticized to the point of<br />

fantasy. How is it that two such beautifully ferallooking<br />

young people with no money or connections,<br />

who later would go on to achieve such extreme<br />

success—Smith with her music and Mapplethorpe<br />

with his photography—found each other? It is a myth<br />

of New York City as it once was, a place where misfits<br />

magically gravitated toward one another at the<br />

chance crossroads of a creative revolution. That’s<br />

one way to look at it. But Smith’s new memoir, Just<br />

Kids (Ecco)—which traces her relationship with<br />

Mapplethorpe from their first meetings (there were<br />

two of them before one fateful night in Tompkins<br />

Square Park) to their days in and out of hotels, love<br />

affairs, creative collaborations, nightclubs, and gritty<br />

neighborhoods—paints a radically different picture.<br />

In this account, the two struggle to pay for food and<br />

shelter, looking out for each other and sacrificing<br />

everything they have for the purpose of making art.<br />

Just Kids portrays their mythic status as the product<br />

of willful determination as much as destiny. Smith’s<br />

immensely personal storytelling also rectifies certain<br />

mistaken notions about the pair, revealing specifically<br />

that they were not wild-child drug addicts but dreamers,<br />

more human and loving than their cold, isolated<br />

stares and sharp, skinny bodies in early photos lead<br />

one to believe. Smith left New York for Detroit in<br />

1979 to live with the man she would eventually marry,<br />

the late former MC5 guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith, just<br />

as Mapplethorpe’s career as one of the most shocking<br />

and potent art photographers was reaching its<br />

apogee (his black-and-whites of gay hustlers, S&M<br />

acts, flowers, and children were headed to museum<br />

collections and a court trial for obscenity charges).<br />

By then Smith had already produced Horses and<br />

had risen to international fame. Her book follows<br />

Mapplethorpe all the way to his death in 1989<br />

from complications due to AIDS, but it’s mostly<br />

about two kids who held on to each other.<br />

As I began reading Just Kids, Smith hadn’t yet<br />

officially agreed to an interview, but I continued to<br />

move through it, spending an entire Sunday in my<br />

apartment unable to let go of the book. I finally had<br />

to put it down to attend a cocktail party at a friend’s<br />

house, and when I got there, I saw <strong>Patti</strong> Smith across<br />

the room. I went up to her, and we made a date for the<br />

interview. It’s this kind of chance meeting that makes<br />

you think there’s some magic left in New York. We<br />

met at a café that Smith has been going to since she<br />

first moved to the city. She ordered Egyptian chamomile<br />

tea, and I ordered an Americano.<br />

PATTI SMITH: That’s what I drink. I’ve already<br />

had two.<br />

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: I can drink an endless<br />

amount of coffee. I’m sure one day that will catch<br />

up with me.<br />

SMITH: I used to drink like 14 cups a day. I was<br />

a pretty speedy person, but I never noticed. Then,<br />

when I was pregnant, I had to give up coffee. After<br />

that, I cut down to five or six cups. Ever since I hit<br />

60, I drink only two. What I do is I get an Americano<br />

and a pot of water and I keep diluting it, because it’s<br />

not even the coffee, it’s the habit.<br />

BOLLEN: That’s my problem. I really don’t<br />

smoke cigarettes that much except when I write.<br />

But when I write, I smoke. It’s bad, but I’m scared<br />

that if I break the habit, I won’t be able to write.<br />

SMITH: It’s part of your process. It’s what you<br />

have to do. I’ll tell you how to break it. You don’t<br />

have to. Like, coffee was part of my process. Now,<br />

if I want to go to a café and write and drink coffee<br />

for two hours, I just order them. I don’t drink<br />

them. A lot is just aesthetic. So you light your cigarette<br />

and let it sit there and don’t smoke it.<br />

BOLLEN: Do you think that would work?<br />

SMITH: If you attach anything harmful to the<br />

creative process, you have to do that. If you learn<br />

“i ReallY believe that<br />

RobeRt Sought not to<br />

deStRoY oRdeR, but to<br />

ReoRdeR, to Reinvent,<br />

and to cReate a new<br />

oRdeR. i know that he<br />

alwaYS wanted to do<br />

Something that no one<br />

elSe had done. that waS<br />

veRY imPoRtant to him.”<br />

nothing else from me, this is a really important lesson.<br />

I’ve seen a lot of people go down because they<br />

attach a substance to their creative process. A lot of it<br />

is purely habitual. They don’t need it, but they think<br />

they do, so it becomes entrenched. Like, I can’t go<br />

without my coffee. I can go without drinking it, but I<br />

can’t go without it nearby. It’s the feeling of how cool<br />

I feel with my coffee. Because I don’t feel cool with<br />

this tea. [<strong>Bollen</strong> laughs] You know, there are pictures<br />

of me with cigarettes in the ’70s, and everybody<br />

thought I smoked. I can’t smoke because I had TB<br />

when I was a kid. But I loved the look of smoking—<br />

like Bette Davis and Jeanne Moreau. So I would have<br />

cigarettes and just light ’em and take a couple puffs,<br />

but mostly hold them. Some people said that was<br />

hypocritical. But in my world, it wasn’t hypocritical<br />

at all. I wasn’t interested in actually smoking them. I<br />

just liked holding them to look cool. All right, was it<br />

a bad image to show people? I’m happy to let people<br />

know I wasn’t really smoking.<br />

BOLLEN: I think it’s almost part of the romance<br />

of creating. As an artist, you kind of have to buy into<br />

your own romance a bit when you are making work.<br />

SMITH: Yep. Except for me, I haven’t really<br />

changed at all since I was 11. I still dress the<br />

same. I still have the same manners of study. Like<br />

when I was a kid, I wanted to write a poem about<br />

Simón Bolívar. I went to the library and read<br />

everything I could. I wrote copious notes. I had<br />

40 pages of notes just to write a small poem. So<br />

my process hasn’t changed much. The way I dress<br />

certainly hasn’t changed. When I was a kid, I<br />

wore dungarees and little boatneck shirts and<br />

braids. I dressed like that throughout the ’50s, to<br />

the horror of my parents and teachers.<br />

BOLLEN: Most people take a long time to find<br />

themselves—if they ever do. How did you catch<br />

on so early?<br />

SMITH: Because even as a kid, I wanted to be an artist.<br />

I also did not want to be trapped in the ’50s idea of<br />

gender. I grew up in the ’50s, when the girls wore really<br />

bright red lipstick and nail polish, and they smelled<br />

like Eau de Paris. Their world just didn’t attract me.<br />

I hid in the world of the artist—first the 19th-century<br />

artists, then the Beats. And Peter Pan.<br />

BOLLEN: Were you always attracted to New<br />

York City?<br />

SMITH: No. As a kid I didn’t really know about<br />

New York City. I’m from the Philadelphia area. I<br />

came to New York through art, really. I went to the<br />

Museum of Modern Art to see the Guernica. And I<br />

wanted to see Nina Simone, so I saved my money<br />

and went to see her at the Village Gate. For me, it<br />

was a lot of money even if it was just a few dollars. I<br />

was making $22 a week working at a factory. So a day<br />

in New York was half my week’s pay. I always wanted<br />

to be an artist, but I never doubted that I would have<br />

to work. Having a job was part of my upbringing.<br />

BOLLEN: That’s what I like about the book. Even<br />

with all of the youthful idealism and craziness, so<br />

many of the chapters deal with struggling to survive.<br />

You basically showed up in New York with no money<br />

and had to get a job so you could eat.<br />

SMITH: Yeah. I came from a family that had no<br />

money. I didn’t have any idea that I would ever<br />

get anything for nothing. So my first thought<br />

stepping out on New York soil was to find a job.<br />

It took a while, but I got one. I got a few. I lucked<br />

out at Scribner Book Store, because it turned out<br />

to be the longest-running job of my life.<br />

BOLLEN: People see pictures of you and Robert<br />

Mapplethorpe in those early days and romanticize<br />

that kind of poverty and struggling. And it<br />

is beautiful, no question. But hunger is hunger,<br />

no matter what decade you live in. You say in the<br />

prologue to the book that Mapplethorpe’s life has<br />

been romanticized and damned, but in the end,<br />

the real Mapplethorpe lies in his art.<br />

SMITH: Exactly.<br />

BOLLEN: So if we have his art, why did you feel<br />

like you had to write a memoir about him?<br />

SMITH: Well, because I finally finished it. I promised<br />

Robert on his deathbed that I would write it. I<br />

kept notes for it and wrote other pieces for him, like<br />

The Coral Sea [W.W. Norton, 1996]. But it took a<br />

while, because the idea of writing a memoir about<br />

a departed friend while also having to navigate widowhood<br />

was too painful. For a while I had to sort of<br />

shelve the promise I made to Robert. In the last 10<br />

years, I finally got back on my feet and got the house<br />

in order, literally and figuratively. I was able to start<br />

again. I know it seems like a fairly simple book to<br />

take 10 years to write, but I had to gather the material<br />

and think out the structure. And sometimes,<br />

truthfully, it was painful. It made me miss him, you<br />

know? Sometimes I’d remember the atmosphere of<br />

our youth with such clarity that it hurt. So I’d have to<br />

let go of it for months and months.<br />

BOLLEN: Do you know why Mapplethorpe wanted<br />

you to make that promise? Did he think remembering<br />

those early days was important to his work or<br />

that people wouldn’t otherwise understand him?<br />

SMITH: Robert absolutely wanted to be remembered.<br />

And he died right in the middle of his prime. Believe me,<br />

if Robert had lived, we would have seen unimaginable<br />

work. He was hardly finished as an artist.<br />

“<strong>robert</strong> and i were<br />

always ourselves—<br />

’til the day he died,<br />

we were just<br />

exactly as we were<br />

when we met. And we<br />

loved each other.<br />

everybody wants<br />

to define everything.<br />

is it necessary<br />

to define love?”<br />

Top lefT: <strong>Patti</strong> Smith at PhotogRaPheR JudY linn’S<br />

bRooklYn aPaRtment, ciRca 1969. Top righT and<br />

cenTer: RobeRt maPPlethoRPe and Smith at<br />

the chelSea hotel, ciRca 1969. BoTTom righT:<br />

maPPlethoRPe at the loft he ShaRed with Smith on<br />

23rd StReet in new YoRk, ciRca 1969. phoTos: JudY linn.

BOLLEN: He was only 42.<br />

SMITH: Yes. I’m 63, and I still think I have yet to do<br />

my best work. He had so many ideas. We talked at<br />

length about the things he wanted to do. I also know<br />

that I was the only one who could write this story.<br />

I’m the only one who knew him so intimately. And<br />

he also knew me. He knew I would serve him well.<br />

Robert and I both loved the magic of things. And of all<br />

the things that have been written about him, I never<br />

found one that maintained the magic of our relationship<br />

or our creative process—and our real struggles,<br />

which were very youthful struggles. Whenever I read<br />

the biography of a young artist—say, Rimbaud—the<br />

biographer sits in such judgment of the young person.<br />

They talk about how Rimbaud did all these<br />

terrible things, like walking around smoking a pipe<br />

upside-down or wearing ragged clothes. He was a<br />

teenager! How can a biographer sit in judgment<br />

of a teenager? That’s how they dress. Those are the pure<br />

years when you’re discovering yourself, when you’re<br />

trying things out, when you have the arrogance of<br />

adolescence. This is a beautiful time, and it has to<br />

be judged in accordance with that. You know, I still<br />

remember what it tastes like to be 11, 17, 27. I wanted—<br />

if I could—to capture that without irony or sarcasm.<br />

BOLLEN: When you arrived in New York in the<br />

late ’60s, you were coming to the city at the peak of<br />

an incredibly creative, revolutionary moment. But it<br />

wasn’t just luck that you arrived when you did. You<br />

and the world you lived in were a big part of what<br />

made it that creative, revolutionary moment.<br />

SMITH: We didn’t know. Sometimes people say to<br />

me, “Oh, you knew all these famous people.” Well,<br />

none of us were famous. And even the people who<br />

were supposedly famous and had some money didn’t<br />

seem much different from the rest of us. I mean, if<br />

you sat in a room with people like Janis Joplin, they<br />

had arrogance, but they didn’t have bodyguards or<br />

paparazzi around them or tons of money. What I’m<br />

saying is, that line between us and them was easy to<br />

walk across. It was just that the greatness in their work<br />

was undeniable, and their arrogance or indulgences<br />

were more palatable. Still, they were human beings.<br />

BOLLEN: Did you think those years of struggling—<br />

not being able to find places to sleep, crashing in bad<br />

hotels—were necessary to become an artist?<br />

SMITH: Oh, yeah. First, almost as a precursor to<br />

that, I came from a struggling family. My father was<br />

on strike from the factory a lot. My mother did ironing<br />

and waitressing. She had four kids who were sickly.<br />

There wasn’t always plenty to eat. So struggling was a<br />

part of my heritage. But I also read the biographies<br />

of struggling artists. I respected Baudelaire, who was<br />

starving. Rimbaud almost starved to death. It was part<br />

of the deal. I wasn’t afraid. I was a very romantic kid.<br />

Struggling and starving were the privileges of being<br />

an artist. And, more importantly, it was a time before<br />

credit cards. If you didn’t have money in your pocket,<br />

you didn’t eat. There were no such things as credit<br />

cards. There was a little bit of bartering but no credit.<br />

BOLLEN: Credit cards really did change life as<br />

we knew it.<br />

SMITH: I think credit cards are one of the evils of<br />

the world. I always knew they would be. I remember<br />

when they started, you’d get credit cards for free in<br />

the mail, and people would just charge things and say,<br />

“Look at this stereo I got.” And I’d say, “How are you<br />

going to pay for it?” “Oh, I don’t have to pay for it.”<br />

BOLLEN: I don’t have to pay, because I have a<br />

credit card. Credit cards are like Santa Claus.<br />

SMITH: Well, they didn’t pay. They’d move. And a<br />

lot of businesses suffered. Also, people’s concept of<br />

material things changed very swiftly. When Robert<br />

and I were living in the Chelsea, no one had a camera.<br />

You had a camera if you were a photographer.<br />

Or if you had money. That’s why all documentation<br />

today is different.<br />

BOLLEN: Do you think that limited contact with<br />

cameras allowed Robert, when your neighbor first<br />

lent him her Polaroid, to see photography as some<br />

sort of special privilege?<br />

SMITH: Oh, Robert was an artist. I mean, a lot of<br />

these things don’t matter with somebody like Robert,<br />

because he was a true artist. Some things magnify<br />

people or open up areas, but Robert always knew he<br />

was an artist. He wasn’t intimidated by technology<br />

or the lack of it. He was just more frustrated. He was<br />

very frustrated when we were young, because he was<br />

a visionary in a very Marcel Duchamp sort of way. He<br />

envisioned whole rooms, big installations, things he<br />

couldn’t realize because he didn’t have any money. It<br />

“to me, being<br />

hungRY and meSSY<br />

and being fRee to<br />

live in a meSS and<br />

not have to woRRY if<br />

i bathed foR a week,<br />

that waS enough.<br />

but a lot of theSe<br />

PeoPle kePt PuShing,<br />

PuShing, PuShing.”<br />

wasn’t that he had to be introduced to anything. Robert<br />

knew about photography. He had taken pictures<br />

before, with a 35 mm. But he wasn’t so interested in<br />

the darkroom process. He liked the Polaroid because it<br />

was fast. Then he was seduced by photography in general—but,<br />

again, because of its speed. He could access<br />

sculpture through photography. He loved sculpture.<br />

BOLLEN: There is a certain amount of magic in the<br />

memoir. You write about your work and events that<br />

involve magic. And I think that fits into this rather<br />

magical time of the late ’60s and ’70s in New York.<br />

SMITH: I didn’t realize it. But I’ve noticed and<br />

tried not to be seduced by the fact that I’ve always<br />

had both very good and very bad luck. I never<br />

understood why, and it’s continued my whole life.<br />

Sometimes I feel like I’m too lucky, and other times I<br />

feel like I’ve been dealt a rough hand. But we weren’t<br />

particularly self-conscious when we were doing all of<br />

those things I wrote about. I didn’t look around and<br />

think, Ah, we are in the era. Because, don’t forget,<br />

I’m a 19th-century person. I spent a lot of time wishing<br />

I had been born in another century. I was always<br />

looking backward. And it took me a long time to<br />

appreciate the present. Change was always horrifying<br />

to me. I always wanted things to stay as they were<br />

and never change. But, honestly, I just didn’t think<br />

about it, because we were struggling. One time, me,<br />

Robert, and Jim Carroll were all living together—<br />

three people with promise. But half the time we<br />

barely had enough money to eat. A lot of our<br />

preocupation was with how to pay the rent and get<br />

our next meal, or a little nickel bag of pot, or supplies<br />

to do a drawing. Our preoccupations were so practical.<br />

You didn’t have a lot of cash unless you stole it.<br />

BOLLEN: It was more about survival.<br />

SMITH: Yeah, it’s different now. Today, people<br />

are very self-conscious about fame and fortune and<br />

where they are at. They can almost gauge it as it’s<br />

happening, by how many hits they have on their websites.<br />

But when I talk about the past, I’m not talking<br />

about it like, “Oh, the good old days.” It was just the<br />

way it was. I could mourn the way things are. I could<br />

mourn the birth of the credit card, but I also know<br />

that because of the credit card, a lot of people are<br />

able to do their work. If Robert had had a credit card,<br />

he could have done those installations. So there’s<br />

good and evil attached. I always think that eventually<br />

true artists will be heard. Sometimes not in their<br />

own time. Look at William Blake. He was completely<br />

drowned out by the Industrial Revolution.<br />

His voice was not heard in his own time because<br />

everything became very material. He was churning<br />

out his hand-colored books while down the road<br />

there was a mill churning out thousands of books at a<br />

time. Almost overnight, William Blake was rendered<br />

obsolete. And today an artist like myself could be<br />

rendered obsolete, except I refuse. I just do my work.<br />

Good artists will rise up. They will be found.<br />

BOLLEN: But maybe New York isn’t the place it<br />

was for artists. Maybe it’s not the right city for<br />

the strugglers and drifters anymore.<br />

SMITH: Oh, yes. It’s very unfair to young struggling<br />

people. When I came to New York in the late<br />

’60s, you could find an apartment for $50 or $60 a<br />

month. You could get a job in a bookstore or be a<br />

waitress and still live as an artist. You could have<br />

raw space. That’s been rendered impossible. I mean,<br />

my band lost its practice space and had to move out<br />

of town. They’re all fancy galleries. CBGB is now a<br />

fancy clothing store. The Bowery used to be home to<br />

winos, William Burroughs, and punk rockers. Now<br />

it’s a whole other scene. That’s part of New York’s<br />

tragedy and beauty. It’s a city of continual reinvention<br />

and transformation. I think the way things are<br />

going now is good for commerce, bad for art. Bad for<br />

the common man. [Mayor Michael] Bloomberg does<br />

not serve the common man. He serves the image of<br />

the city as a new shopping center. A place to get great<br />

meals. Little parks that make no sense. Places like<br />

Union Square, as if we were in Paris. We’re not Paris.<br />

We’re New York City. It’s a gritty city. It’s a place<br />

where you have all races and all walks of life, and<br />

that has always been its beauty. It’s the city of immigrants.<br />

It’s the city where you can start at the bottom.<br />

I feel the Bloomberg administration has reinvented<br />

the city as the new hip suburbia. It’s a tourist<br />

city. It’s really safe for tourists. I guess I liked it when<br />

it was a little less safe. Or I liked it when it was safer<br />

for artists. Now it’s unsafe for artists. I’m not saying<br />

this for myself. I’m saying this for the future of creative<br />

communities. Because, one day, all the people<br />

who have driven out the artists and have only these<br />

fancy condos left are going to turn around and say,<br />

“Why do I live here? There’s nothing happening!”<br />

BOLLEN: What’s very moving throughout the book<br />

is how you and Robert took care of each other. And<br />

it’s rare that in a relationship between two young<br />

people, you both became so successful. Usually the<br />

support system eventually becomes unbalanced, and<br />

one rises while the other holds on. Would either of<br />

you have made the work you did without each other?<br />

SMITH: Robert was a great artist, and he would<br />

have found a way, and I would’ve done whatever I<br />

do. But I know what we gave each other. We gave<br />

each other what the other didn’t have. I was very<br />

sturdy and practical in my own way. So I gave him a<br />

practical support system and also unconditional<br />

belief. He already had that in himself, but it was nice<br />

to have someone conspire with him. I had a lot of<br />

bravado, and I was a good survivor. But I can’t say<br />

that I believed in myself as an artist with the full<br />

intensity that he believed in his own self. He gave me<br />

that. I certainly don’t count myself as any reason why<br />

Robert did great work. I just know that in those formative<br />

years . . . I know I kept him going.<br />

BOLLEN: You were first lovers and then close<br />

friends and collaborators. You were something of a<br />

constant when Mapplethorpe was going though so<br />

much self-reinvention and self-discovery. The way<br />

you describe it in the memoir, it almost seems like it<br />

was ripping him apart.<br />

SMITH: I was always a constant because Robert had<br />

a lot of duality. Part of it was his Catholicism and<br />

how he was brought up—good versus evil, being<br />

straight versus being homosexual. They were<br />

battling in him until he got to a point where these<br />

things were no longer a battle. They were just all<br />

of the things that he was. Robert and I were always<br />

ourselves—’til the day he died, we were just exactly<br />

as we were when we met. And we loved each<br />

other. Everybody wants to define everything. Is it<br />

necessary to define love? We just loved each other.<br />

BOLLEN: He shot really beautiful photos of you.<br />

SMITH: I liked being photographed back then. I<br />

was tall and skinny, and I used to dream about being<br />

a model. But I was too weird. I mean, my look back<br />

then was too weird for modeling. But I never felt<br />

self-conscious in front of a camera, so we didn’t have<br />

to deal with that. The rest was just me and him. I don’t<br />

even remember a camera. It’s like, when Robert took<br />

pictures, I could see his face. When I remember it, I<br />

never see a camera there. I always see his eyes squint,<br />

the way he looked at me, or the way he checked to make<br />

sure everything was right. He knew what he wanted.<br />

Robert was not an accidental photographer. He didn’t<br />

shoot and then find something cool in the images<br />

later. He knew what he wanted, got it, and that was it.<br />

BOLLEN: Were you surprised when the photography<br />

veered into homosexual themes and S&M?<br />

SMITH: It wasn’t even homosexual. It was S&M.<br />

For me, S&M is its own world. You can’t call it<br />

homosexual. It’s so specialized. But, yeah, I was<br />

really surprised. I was shocked and frightened,<br />

because the pictures were frightening. Robert<br />

did shocking work. Those pictures should always<br />

be shocking. I shudder to think people could<br />

get used to seeing bloody testicles on a wooden<br />

board. But I was worried about him getting hurt<br />

or killed or something, because it was a world that<br />

I didn’t know anything about.<br />

BOLLEN: You also say that he wasn’t the kind<br />

of person who would shoot voyeuristically. He<br />

would get personally involved.<br />

SMITH: I know that if he was taking pictures,<br />

he would have to involve himself somehow. He<br />

was too honest. I didn’t ask him about all that. It was<br />

too much for me. I still don’t know anything about<br />

what Robert really did in the ’80s. We never talked<br />

about it, and I never read anything, because it didn’t<br />

involve me. I never stood in judgment of Robert.<br />

I just couldn’t involve myself in all the things that<br />

he did. I could only support him as an artist and<br />

as a person who loved him.<br />

BOLLEN: By the late ’70s, before you moved to<br />

Detroit, your career had already started to move in a<br />

very different orbit. Do you think that split between<br />

you and Robert geographically was necessary?<br />

SMITH: No. Without sounding conceited, I was at<br />

the height of my fame. I was—in Europe, at least—<br />

becoming a really big rock ’n’ roll star. I was performing<br />

before 80,000 people, as big an audience as one<br />

could imagine. It had nothing to do with Robert. It was<br />

just that I had found the person I loved, and that was<br />

how we decided to conduct our lives. Fred [Smith] had<br />

been really famous as a young man, in the MC5. And<br />

then he got hurt by fame, crushed by it. We just agreed<br />

to put all that behind us and start over again as human<br />

beings and find out what it meant to be human.<br />

BOLLEN: Did you need to leave New York to do that?<br />

SMITH: Well, to be with Fred, I had to. He lived<br />

in Detroit. So I deferred to him. I didn’t want to<br />

leave New York. I loved New York. It was difficult<br />

to leave. It was difficult to leave Robert and my band.<br />

None of that was easy. But as fate turned out, those<br />

16 years were the only years I was ever gonna spend<br />

with Fred. So I made the right decision. They weren’t<br />

years, in the end, that I had a choice to play with.<br />

“the queStion foR me<br />

waSn’t if aRt got uS. the<br />

queStion waS, ‘do we<br />

RegRet that?’ i know<br />

aRt got uS, becauSe if<br />

aRt getS You, You neveR<br />

can be noRmal. You can<br />

neveR enJoY. You can’t<br />

go anYwheRe without<br />

tRYing to tRanSfoRm it.”<br />

BOLLEN: You mention at one point in the book,<br />

when you are sitting around the back room at Max’s<br />

Kansas City, that none of the people at the table would<br />

die in the Vietnam War, but most of them would die in<br />

the plagues of the coming decades. It obviously must<br />

have been hard when writing this book to look back at<br />

all of the people that once were here but now are gone.<br />

SMITH: I can look at that table and see everybody<br />

there and see only two survivors in all of those people<br />

who were iconic of those times. Jackie Curtis,<br />

Andrea Feldman, Candy Darling, Andy Warhol—<br />

all of these people are gone. All the players—even<br />

the kings and queens—Halston, all of them.<br />

BOLLEN: Why did the brilliant eccentrics of<br />

that period have such a high mortality rate?<br />

SMITH: Well, I can’t say I felt any less eccentric than<br />

anybody else. I just think that some people were more<br />

attracted to the lifestyle around art. To me, being<br />

hungry and messy and being free to live in a mess<br />

and not have to worry if I bathed for a week, that was<br />

enough. But a lot of these people kept pushing, pushing,<br />

pushing—doing drugs, indulging in very intense<br />

promiscuity, taking hormonal drugs to change their<br />

gender. There were all kinds of things—speed,<br />

mixing pills. I’ve often thought about what made me<br />

different than a lot of these people. Maybe it’s the fact<br />

that even though I had a very sickly childhood, I had<br />

a happy childhood. I was well loved. A lot of these<br />

people were not loved early in their lives. I’m not a<br />

psychiatrist, nor am I trying to be. I’m just saying that<br />

I lived in the same environment as these people. But<br />

also, I hated peer pressure. I suffered it my whole life,<br />

and I refused when I came to New York to get reverse<br />

peer pressure. I hated when I was in high school and<br />

people said I had to drink beer in a field to be cool. I<br />

would be the lookout, but I didn’t want beer. It didn’t<br />

attract me, and I hated that pressure. When I went to<br />

New York, I hated the pressure of “Oh, if you don’t<br />

smoke pot, you’re a narc.” That paranoiac peer pressure<br />

was rampant in those days. There was a lot of<br />

peer pressure to take drugs.<br />

BOLLEN: I have always suspected that for all of the<br />

freedom going on in Warhol’s circle, it was one big<br />

pool of peer pressure.<br />

SMITH: It was heavy. I wasn’t a part of that. That was<br />

too intense for me. It was very brutal—a brutal scene.<br />

But so was the hippie scene. That was the thing—<br />

Robert was like a refuge for me, because Robert knew<br />

that I didn’t need that stuff. For some reason my mind<br />

expanded on its own, and he understood that.<br />

BOLLEN: To be honest, one thing that really surprised<br />

me about the book is that I figured that you<br />

did a lot of drugs at that time. I just assumed drugs<br />

were a big part of you and Mapplethorpe’s life in the<br />

days of the Chelsea Hotel. I was waiting for the chapter<br />

where it would go really deep into drug darkness.<br />

But you were a very sober person.<br />

SMITH: I have a whole different view of drugs.<br />

When the drug culture was prevalent, I was appalled<br />

by it. To me, drugs were quite sacred. I had a romantic<br />

view of drugs. They were for artists and poets and<br />

American Indians and jazz musicians. I never believed<br />

in drugs as a recreational substance. No matter what<br />

people say or what exaggerated stories they tell, I<br />

could count on my hand the number of times I drank<br />

too much tequila with Sam [Shepard] or something.<br />

But it was also because of my body. I had so many<br />

illnesses in my youth. My body actually couldn’t<br />

take substance abuse. I nearly died of illnesses three<br />

different times before I was 20, and the last thing I<br />

wanted to do, after my parents went broke taking<br />

care of me, was to go and throw it away. I’m also too<br />

ambitious. I wanted to do something great, and you<br />

can’t do anything great if you don’t have mental clarity.<br />

Robert also didn’t live the crazy druggy lifestyle<br />

in the ’70s. I mean, he took acid sometimes. But we<br />

had no money. Buying a nickel bag of pot was a big<br />

thing for Robert. If he smoked a joint every day, it<br />

was like some skinny little joint. Also, a person who<br />

was really fucked up on drugs and couldn’t handle<br />

it actually repelled him. If someone came to visit us<br />

who had shot a bunch of heroin or was really fucked<br />

up, he didn’t like that. He didn’t like to see people<br />

lose control. I only saw Robert lose control on a substance<br />

once in my life. I never saw him drunk. Sometimes<br />

on New Year’s Eve, he’d have a couple glasses<br />

of champagne. But Robert was very much in control<br />

of himself. What he did later in life or beyond our<br />

sphere I can’t speak of, but I knew him for a long time<br />

as a person who had control of himself.<br />

BOLLEN: Maybe some of his graphic sexual portraits<br />

were his way of gaining control over the situation.<br />

SMITH: Robert liked to control situations. Robert was<br />

an artist. I’m not an analytical person. I’ve tried to analyze<br />

a few things sitting here, but in reality, I spend most<br />

of my time dreaming up work for magic scenarios.<br />

BOLLEN: Do you have a lot of your early drawings<br />

and work from that period?<br />

SMITH: I have some. A lot of them were destroyed<br />

when we were robbed. I have certain things. I have<br />

Robert’s letters to me. I have precious things. I don’t<br />

have any photographs. We were so communal, I<br />

always imagined what ¬ continued on page 125<br />

chRiStoPheR bollen iS inTerview’S editoR at laRge.<br />

see and hear more paTTi smiTh on inteRviewmagazine.com<br />

98 99

124/MORE!MORE!MORE! 125<br />

more burton<br />

Continued from page 42 ¬ this perception of him as a<br />

teen idol, but he’s really not that person. That’s just<br />

how he was perceived by society—and thus who he<br />

was. And that’s exactly like Edward: I’m not what<br />

people think I am. I’m something else.<br />

ELFMAN: You got all that just from meeting him?<br />

BURTON: Yeah, absolutely. That’s the thing. I could<br />

tell that he understood. You can always feel if someone<br />

understands the dynamic. There’s a certain pain<br />

in that. Johnny’s not Tiger Beat, even if that’s how the<br />

rest of the world sees him—as a page of a teen magazine.<br />

He’s got a lot more depth, a lot more emotion.<br />

There’s a certain sadness when that happens to people.<br />

So it’s very easy to identify without even really talking<br />

too much about it.<br />

ELFMAN: You’re known for working on amazing<br />

sets and compositing shots that use as few<br />

effects as possible—maybe with the exception<br />

of Mars Attacks!, and even then you had sets and<br />

actors and animated Martians that were realized<br />

pretty quickly. Now we are about to see Alice in<br />

Wonderland, which is a totally different animal.<br />

What was it like working on that?<br />

BURTON: It was completely opposite from the<br />

way I usually make a film. Usually the first thing<br />

I know is the vibe and feel of a scene. It’s the first<br />

thing you see. Now it’s the last thing you see. It’s<br />

like actually being in Alice in Wonderland. It’s completely<br />

fucked up. You understand that when you’re<br />

shooting—that some percentage of what you’re<br />

filming isn’t going to be exactly like what it ends<br />

up being, because so many elements are added<br />

later. It’s in your head, and it can be unsettling. I<br />

did find it quite difficult, because you don’t see a<br />

shot until the very end of the process. Even when<br />

we were making Nightmare or Corpse Bride, you’d<br />

get a couple of shots and know what the vibe was.<br />

This was completely ass-backward.<br />

ELFMAN: Let’s end with a little free association.<br />

BURTON: Uh-oh. Always a bad sign.<br />

ELFMAN: As a kid, what was your idea of reality?<br />

BURTON: Well, it’s those things that I always loved.<br />

People say, “Monster movies—they’re all fantasy.”<br />

Well, fantasy isn’t fantasy—it’s reality if it connects<br />

to you. I always found that those people trying to categorize<br />

normal versus abnormal or light versus dark,<br />

yada yada, are all missing the point.<br />

ELFMAN: I remember what you said to me when you<br />

were fighting the R rating on Batman Returns, which<br />

was absurd because there was nothing really violent<br />

in the whole movie to put an R rating on. You said,<br />

“You know what’s scary to a little kid? When they<br />

hear one of their relatives coming home and knocking<br />

over furniture because they’re drunk. That’s<br />

frightening to a kid. Not monsters!”<br />

BURTON: Exactly! Or when an aunt who has bloodred<br />

lipstick and lips three feet long comes to kiss you<br />

dead-on on your face. That’s terrifying!<br />

ELFMAN: [laughs] Okay. Freaks.<br />

BURTON: We’ve all been called that before. [laughs]<br />

When I hear that word, I hear, “Somebody that I would<br />

probably like to meet and would get along with.”<br />

ELFMAN: Good and evil.<br />

BURTON: Hard to tell sometimes. That’s the thing.<br />

Especially when you’re making a movie, you experience<br />

good and evil about 20 to 100 times a day.<br />

You’re not quite sure where one crosses over into the<br />

other. It’s quite a slippery slope, that one.<br />

ELFMAN: Last question. I’ve always wondered, but<br />

I’ve never really asked you: Why in the world did I<br />

get hired to do Pee-wee’s Big Adventure? Because it<br />

didn’t make any sense, even to me.<br />

BURTON: [laughs] We never talked about it, did we?<br />

It’s very simple to me. I used to come to see your band<br />

play at places like Madame Wong’s.<br />

ELFMAN: But that’s so different from film scoring.<br />

BURTON: It wasn’t to me. I always thought you<br />

were very filmic in some way. Also, because I hadn’t<br />

made a feature-length film yet, I just responded<br />

to your work. It was very nice to be connected to<br />

somebody who I felt had done so much more than<br />

I had at that point.<br />

ELFMAN: Johnny and I both owe you a big debt.<br />

BURTON: It’s all great. There’s something quite<br />

exciting when you have a history with somebody<br />

and you see them do new and different things.<br />

We have our next challenge set out for us, that’s<br />

for sure. But let’s have you watch it, and see if you<br />

want to quit.<br />

more JAY-Z<br />

Continued from page 61 ¬ like when you first spotted<br />

him and he was producing for you?<br />

JAY-Z: Well, he’s really more of a peer now. You know,<br />

before, he was more a new guy trying to get on—a<br />

fan of the music that I’ve made and my lifestyle—so<br />

things were a little different. But he’s an extraordinary<br />

person. He has these ideas and these things that he<br />

wants to do and places he wants to go, and he’s really<br />

passionate about them. He’s very sincere.<br />

MITCHELL: Sometimes his passions ruin him.<br />

JAY-Z: Yeah, which is great. I like that, man! I really<br />

do. I mean, no one’s walking around here perfect.<br />

Everyone’s gonna make mistakes. That’s part of how<br />

you learn. I think Kanye . . . Well, I know he said<br />

what he believed. He was telling the truth.<br />

MITCHELL: To which event are you referring?<br />

JAY-Z: I’m talking about the Taylor Swift thing. I just<br />

think the timing of what he did was wrong, and that,<br />

of course, overshadowed everything. He believed<br />

that “Single Ladies” [by Jay-Z’s wife, Beyoncé] was<br />

a better video. I believed that. I think a lot of people<br />

believed that. You can’t give someone Video of the<br />

Year if they don’t win Best Female Video. I thought<br />

Best Female Video was something you won on the<br />

way to Video of the Year. But, hey, I guess it wasn’t—<br />

and that’s a whole other conversation about awards<br />

shows and artists.<br />

MITCHELL: You seem to stay away from that awards<br />

show stuff for the most part.<br />

JAY-Z: Yeah, because it ain’t about nothing. It’s cool.<br />

It’s acknowledgment. The fans get to see you, and<br />

you can do great by your record if you have a great<br />

performance or a great night there. That’s all part of<br />

the business. But at their core, awards shows are not<br />

really a sincere thing. You know, for a lot of years,<br />

the artists had to pay to play their own set.<br />

MITCHELL: No kidding!<br />

JAY-Z: Yes. That was the worst scam ever. I<br />

couldn’t even believe it. I mean, just now they’re<br />

starting to pay for half the sets and some awards<br />

shows pay for the whole thing. But this is just<br />

happening now—and it’s only because the record<br />

companies ran out of money.<br />

MITCHELL: You’ve always had interesting takes on<br />

awards shows. I remember back in the day, you talked<br />

about the Grammys and said, “Well, they don’t take<br />

rap seriously, so why should I go? They don’t know<br />

what we do—and they don’t care about what we do.”<br />

JAY-Z: It’s just honest, man—they really didn’t. I’ve<br />

always seen awards shows for what they are. For the<br />

awards show people, it’s about sponsorships—it’s not<br />

about recognizing anyone’s art, because if you get into<br />

the business of recognizing art, then you have to get<br />

it right all the time. You have to get it right. You can’t<br />

have the woman who wins Video of the Year not win<br />

Best Female Video. I mean, Herbie Hancock is great,<br />

but you can’t have him beat the Kanye album that year.<br />

I mean, come on, seriously. That can’t happen. That<br />

just lets me know that the people who get to pick these<br />

ballots just check the only name they know. I think<br />

that’s what’s happening with rap music now.<br />

MITCHELL: Yeah?<br />

JAY-Z: I think it’s a bunch of people who don’t<br />

know anything about rap, and have probably never<br />

even heard a Kanye West album, are doing the<br />

nominating, and they say, “Kanye West. I know<br />

that name. That’s the guy who made the comments<br />

about the president that time! He’s nominated!”<br />

That’s how the process works, and I think<br />

that’s part of Kanye’s frustration. Me, I look at it<br />

for what it is. But Kanye is so passionate about it.<br />

I mean, the guy shot three “Jesus Walks” videos.<br />

Three. Two of them he shot with his own money<br />

just so he could get it right. He really cares about<br />

it. And then, back to the original point, his passion<br />

kicks in and he takes things too far . . . He<br />

doesn’t realize that that girl, Taylor Swift, is just<br />

like him. That was her moment. It wasn’t her fault.<br />

She didn’t do anything. It’s not her awards show.<br />

So he just did the wrong thing to the wrong person<br />

at the wrong time.<br />

MITCHELL: Did he call you that night? Did you<br />

guys talk about what happened right away?<br />

JAY-Z: We actually had to fly out because we were<br />

doing Leno the next day, and he called and said he<br />

wasn’t getting on the plane. I knew he didn’t want to<br />

have the conversation yet. It’s more of a big brother<br />

relationship with me and him. But he came the next<br />

day, and we spoke in the dressing room. We had a<br />

nice, long talk. I think he did the right thing to face it<br />

and just move on. I say this all the time, but I think, at<br />

the end of the day, we’re gonna celebrate him for his<br />

passion more than vilify him.<br />

MITCHELL: Well, with the way that black music—rap,<br />

hip-hop—has become a more mainstream thing, you get<br />

a lot of people responding to your music who don’t necessarily<br />

know the history or what you’ve been doing.<br />

JAY-Z: It’s the worst thing in the world. In a weird<br />

way, it’s funny to me. It’s the reason I made “99 Problems.”<br />

I was like, “People are gonna hear the chorus<br />

and think one thing without listening to the context<br />

or what the song is really about.” “I got 99 problems<br />

but a bitch ain’t one,” It’s like, “See? Bitches and hoes!<br />

That’s it. That’s all he’s about.” Right? The song is<br />

really about racial profiling. But there are advantages.<br />

I was thinking about this the other day. Forget about<br />

New York people—they know me. But all over the<br />

world, people talk to me like they’ve had a conversation<br />

with me before, and it’s the best feeling. I like it<br />

when people I don’t even know call me “Jay.” It happens<br />

all the time. I know these people don’t know me,<br />

but it’s because they listen to my music so much that<br />

they feel they know me. It can be overwhelming—<br />

certain people think they can just sit at the dinner<br />

table with you. But for the most part it’s really cool.<br />

Wherever I am, I don’t feel disconnected. It’s really<br />

this weird, warm feeling.<br />

MITCHELL: It’s like, through your music, you pull<br />

people into what’s going on in your world, and so<br />

they feel like they know you. Who was the first musical<br />

person who connected with you in that way?<br />

JAY-Z: In my house, we listened to so much great<br />

music that I never really connected to one specific<br />

thing. There was Michael Jackson, of course, but he<br />

didn’t speak to me. I guess it had to be early rap—you<br />

know, Rakim and Big Daddy Kane and Ice Cube. I<br />

would say those three all spoke to me directly, maybe<br />

Rakim a little more because he was around some real<br />

guys from a project that was like 10 minutes away<br />

from Fort Greene projects. But it was weird for me,<br />

man, because my lifestyle was so different. The rappers<br />

in that day, although they made money, they<br />

weren’t making more money than the street guys.<br />

MITCHELL: I think people lose sight of that. For a<br />

long time, there wasn’t that much money in rap. But<br />

if you had a hustle, if you were out there doing your<br />

thing, you could really knock it down.<br />

JAY-Z: Yeah. So although I connected with those<br />

records, I could never fully connect because the guys<br />

that I was around were bigger than the rappers. Rap<br />

wasn’t all over the radio at that time—in fact, there<br />

were stations that promoted that they didn’t play rap,<br />

like that was a good thing, like, “This is the only place<br />

where we don’t play rap!”<br />

MITCHELL: So what was the game-changer<br />

moment for you?<br />

JAY-Z: It was Jaz [the rapper Jaz-O] for me. Jaz was<br />

my friend. He came from Marcy Projects. When<br />

Jaz got a record deal, it really was a moment for me.<br />

I was like, “So explain this to me: they gave you<br />

money to make music?” He got, like, $400,000,<br />

which was a ridiculous number back then, in, like<br />

’88, because EMI wasn’t in the rap business, and<br />

they didn’t know enough not to jerk him. They<br />

didn’t know that he wasn’t supposed to get money<br />

equivalent to the R&B guys, so they gave him a<br />

contract like they would give, like, Freddie Jackson.<br />

When he got that deal, that was the moment<br />

when I said, “Man, this thing could be something.”<br />

But up until then, I didn’t really believe that rappers<br />

were making that much money because, I’m telling<br />

you, the hustlers used to buy rapper’s rings. You’d<br />

be at a hotel and the hustler would get the presidential<br />

suite, and the rapper would get, like, a twin<br />

bed. The hustler would pull up in a 735 BMW, and<br />

the rapper would pull up in the van—you know, the<br />

turtle top with 18 people in it. So it’s like, “Why<br />

do I want to be a rapper?” That’s why it took me so<br />

long to rap.<br />

MITCHELL: I was wondering: You knew Biggie.<br />

What did you think of that movie Notorious that<br />

came out last year?<br />

JAY-Z: I have an interesting perspective on Notorious<br />

[2009]. I felt like it was entertaining, and it was<br />

done well, but I didn’t enjoy it. The whole time I<br />

was watching it, I just saw Biggie. I saw this charismatic<br />

guy who made it and was very charming and<br />

really just a happy-go-lucky, funny guy who beatboxed<br />

when he got caught cheating—and this guy<br />

died for absolutely nothing. So I couldn’t really get<br />

past that to enjoy the movie. It looked like it was<br />

entertaining—I could see how people were entertained.<br />

But me, I didn’t enjoy it.<br />

MITCHELL: I guess I just wonder if it made you<br />

reflect back on that time and all that craziness. You<br />

know, we look back on that now, and it’s just like,<br />

“Wow, how could that possibly have happened?”<br />

JAY-Z: Right. That part really stuck with me. I’m<br />

like, man, it was just senseless. It was about nothing.<br />

MITCHELL: Did anyone ever ask you if you wanted<br />

to be involved in that film in some way?<br />

JAY-Z: Early on in the process, Mark Pitts [one of<br />

the producers on the film] and Biggie’s mom [Violetta<br />

Wallace] came to my office. They spoke about<br />

what they were trying to do, but nobody talked to<br />

me about being in the movie or anything like that<br />

. . . I try to stay away from those things. Even ask<br />

Puff [Sean “Diddy” Combs]. I give Puff the worst<br />

times when he asks me to be on Biggie records,<br />

because I never want to feel like I’m capitalizing off<br />

someone who’s not here—and I’m not saying that<br />

anyone did. But I’m very sensitive about that stuff.<br />

I’d rather pay homage to him in my own way, and<br />

keep things moving forward.<br />

more ghesquiere<br />

Continued from page 69 ¬ It’s really about emotion and<br />

sensation. Clothes are too, but it’s not the same. Working<br />

with a scent was actually very relaxing for me.<br />

FORD: I think it gives more emotion. This is going to<br />

sound crazy, but the first thing I do when I get home<br />

is take off all my clothes—at home, just around the<br />

house. Like, right now, I am sitting here completely<br />

naked. [Ghesquière laughs] I can’t stand clothes! I take<br />

everything off—my shoes, my socks, my watch, shirt,<br />

everything. I am completely naked.<br />

GHESQUIÈRE: Do you wear your perfume?<br />

FORD: That is what I was going to say. I stay this<br />

way pretty much 24 hours a day. Richard is very<br />

funny. He is usually completely dressed. He does<br />

not like to be naked. So he is in the house; we are<br />

having dinner. I am sitting there naked; he is sitting<br />

there completely dressed. I also take, like, three<br />

baths a day—it is not to be clean, it is because I like<br />

to relax and lie in the water. It is the way I calm<br />

myself down. But every time I walk past my bathroom,<br />

I go in and I put on some perfume. I use different<br />

ones for different moods. If I feel that I need<br />

to calm down, I put on certain fragrances that are<br />

more sensual. If I feel that I need to energize, I put<br />

on something else. Fragrance for me is so important.<br />

How did your fragrance begin?<br />

GHESQUIÈRE: It’s a friendship story. It started<br />

with a conversation Charlotte and I had years ago.<br />

I said, “The day I do a perfume, I’d like to do it for<br />

you.” I could have done something very exclusive<br />

and expensive. But what I like about this perfume is<br />

that it’s the first thing most women can access from<br />

Balenciaga. That was a challenge for me.<br />

FORD: [laughs] Because you don’t care about real<br />

women! We talked about that.<br />

GHESQUIÈRE: In this case, I care.<br />

FORD: Did you work directly with the perfumers?<br />

GHESQUIÈRE: Yes. I worked with Olivier Polge. I<br />

wanted to do a floral, for sure. It’s a violet perfume.<br />

Made of violets.<br />

FORD: I love violet. Oscar Wilde used to wear violet.<br />

GHESQUIÈRE: That’s why I like it, because it has a<br />

real masculine vibe. It’s not timid.<br />

FORD: Well, your clothes are not timid. So, lastly, do<br />

you get panicked five minutes after showing a collection?<br />

The moment I left the runway, I would always<br />

think, What the fuck am I going to do now?<br />

GHESQUIÈRE: That’s exactly what I think.<br />

Exactly. I usually think, I have to go back to the studio<br />

and chose fabrics. Or I like to go quite far away—<br />

FORD: And play golf.<br />

GHESQUIÈRE: Yeah, play golf. Exactly.<br />

more <strong>smith</strong><br />

Continued from page 99 ¬<br />

was his was mine. Even when<br />

we were apart, I always knew that if I needed or<br />

wanted something, I just had to ask him. I never<br />

expected him to die so young.<br />

BOLLEN: I was thinking about that line you remember<br />

him asking you when he was really sick. It’s devastating.<br />

He asked you if it was the art that did this.<br />

SMITH: “Did art get us?”<br />

BOLLEN: Yes, that’s it. And I wondered if art<br />

kind of did. At least for him. It’s not really possible<br />

to answer that question.<br />

SMITH: I can’t answer that. I mean, I know it got me.<br />

The question for me wasn’t if art got us. The question<br />

was, “Do we regret that?” I know art got us, because if<br />

art gets you, you never can be normal. You can never<br />

enjoy. You can’t go anywhere without trying to trans-<br />

form it, you know? You go into church to pray, and<br />

you start writing a story about being in a church praying.<br />

You’re always observing what you do. I noticed<br />

that when I was young going to parties. I could never<br />

lose myself in a party unless I was on the dance floor<br />

because I was always observing—observing or creating<br />

a mental scenario. That’s why performing is probably<br />

the truest thing I do socially, because everything is<br />

natural. There’s nothing fake in the way that my band<br />

performs. I’m not the greatest in social situations. But<br />

onstage, my whole reason for being there is to serve, so<br />

I’m giving everything of myself that I know how.<br />

BOLLEN: There are a lot of misunderstandings<br />

about both you and Mapplethorpe and who you<br />

were. Maybe this will clear some of that up.<br />

SMITH: Sometimes those misunderstandings came<br />

just because of the way I looked: I was skinny, wiry,<br />

speedy; I had a high metabolism rate, tons of energy.<br />

If I had taken speed, I would’ve had a heart attack. I<br />

was already moving at 78 rpm. But you know, I just<br />

wanted to be myself. That’s all I ever wanted, just to<br />

be myself. I don’t like people telling me how to dress,<br />

how to comb my hair. I didn’t set out to hurt anybody’s<br />

feelings, or to shock parents or anything like<br />

that. But you know, sometimes we make choices that<br />

seem to bother everybody but ourselves.<br />

BOLLEN: Do you think Mapplethorpe wanted to<br />

be himself? Is that what he was looking for?<br />

SMITH: Robert had different goals. He came from<br />

a different upbringing. His upbringing was Catholic,<br />

middle class, precise, military, well ordered, spanking<br />

clean. I really believe that Robert sought not to destroy<br />

order, but to reorder, to reinvent, and to create a<br />

new order. I know that he always wanted to do<br />

something that no one else had done. That was very<br />

important to him. I was a little different. I always<br />

wanted to do what somebody else had already done—<br />

I wanted to write the next Peter Pan, the next Alice in<br />

Wonderland. I loved history, and I wanted to be a part<br />

of it. Robert wanted to break from history.<br />

BOLLEN: You told me earlier that Just Kids isn’t<br />

a book about the birth of punk rock. You didn’t<br />

want to do that book.<br />

SMITH: I don’t think I’m qualified to write that<br />

kind of book. We did our work unconsciously and<br />

punk rock evolved around what we were doing.<br />

Lenny Kaye and I started working together in 1971.<br />

We were sort of a bridge between our historical<br />

roots and the great masters. We were a bridge from<br />

Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison and Bob Dylan and<br />

Bo Diddley and all the people in the history of rock<br />

’n’ roll. Lenny Kaye and I saw the whole history of<br />

rock ’n’ roll from the time we were born. The evolution<br />

was within us. New generations come less fettered<br />

with that evolution. They’re touched by it, but<br />

it’s not necessarily in their blood. So they’re going<br />

to do things that are more revolutionary. The whole<br />

history of rock ’n’ roll is sacred. Sometimes in my<br />

life I’ve been given too much credit, and sometimes<br />

I’ve been ignored, but to me it doesn’t matter. I know<br />

what we did, and I know what we’re doing.<br />

BOLLEN: Do you have great hopes for the young<br />

artists of the future?<br />

SMITH: There are powerful possibilities, and I think<br />

they’re gonna do splendid. It’s a dark period now<br />

because everyone is beguiled by fame. We have these<br />

horrible reality shows like American Idol, which is pop<br />

art at its basest, and it’s probably something that Andy<br />

Warhol, in his genius, anticipated. But the artist has<br />

to struggle beneath that canopy, just as we struggled<br />

beneath a different canopy—though ours wasn’t as<br />

overwhelming. True artists just have to keep doing<br />

their work, keep struggling, and keep hold of their<br />

vision. Being a true artist is its own reward. If that’s what<br />

you are, then you are always that. You could be locked

126/MORE!MORE!MORE!<br />

away in a prison with no way at all to communicate,<br />

but you’re still an artist. The imagination and the ability<br />

to transform is what makes one an artist. So young<br />

artists who feel overwhelmed have to almost downscale.<br />

They have to go all the way to this kernel and<br />

believe in themselves, and that’s what Robert gave me.<br />

He believed in that kernel I had, you know, with absolute<br />

unconditional belief. And if you believe it, you’ll<br />

have that your whole life, through the worst times. I<br />

wrote this book because I promised Robert I would.<br />

But I also wrote this book in hopes that maybe it would<br />

somehow inspire. It’s the same reason I made Horses.<br />

BOLLEN: Why did you make Horses?<br />

SMITH: We made Horses to inspire people who, like<br />

us, felt disenfranchised, unloved, disconnected. I<br />

wrote “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine”<br />

when I was 20 or 21 riding the subway to Scribner—<br />

not because I didn’t believe in Jesus or didn’t feel that<br />

he was a great revolutionary. It was about my disconnection<br />

with the church and my dissatisfaction with<br />

the rules of church, which was created by man. And<br />

Jesus felt the same thing. That’s why he did what he<br />

did. He was tearing down the old guard. I’m a pretty<br />

positive person, you know? I was trying to infuse<br />

the record with a certain positivity and also link us<br />

to our history. It was saluting history and also the<br />

future. This book I wrote is like Horses. It’s about a<br />

time and about a girl and a boy who were there when<br />

Horses was being built and committed. So I suppose<br />

it’s seeking to find the people that need it..<br />

more goLdstein<br />

Continued from page 123 ¬<br />

mostly Jean Paul Gaultier,<br />

and I’m friends with him. Before that, I was wearing<br />

Claude Montana extensively. When Roberto<br />

Cavalli first started designing men’s clothes, I was<br />

buying almost the entire Cavalli line every season.<br />

I was very well known for wearing Cavalli—to the<br />

extent that some of the other designers wouldn’t let<br />

me come to their shows.<br />

BLASBERG: When did you start going to shows?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: As far as I remember, I started going<br />

to the shows of the designers whose clothes I wore at<br />

least 20 years ago—particularly Jean Paul Gaultier.<br />

BLASBERG: How would you get the invitations?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: Originally, a friend of mine, Tommy<br />

Perse, who owns Maxfield here in L.A., started<br />

giving me invitations to the Gaultier shows. And then,<br />

as I got more interested in other shows, he would supply<br />

me with more invitations. Eventually, I reached a point<br />

where I could just show up and they’d let me in.<br />

BLASBERG: Have you ever thought about becoming<br />

more involved in fashion, beyond just crashing<br />

the shows?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: In recent years, as I’ve become better<br />

known on the fashion circuit and have stepped up<br />

my appearances at fashion shows, I’ve become so recognizable<br />

that the fashion photographers now swarm<br />

around me when I go to these shows.<br />

BLASBERG: But you like the attention.<br />

GOLDSTEIN: I get a kick out of it. I’m not doing it<br />

for any monetary reason. I’m doing it for fun.<br />

BLASBERG: Let’s talk more about this home.<br />

GOLDSTEIN: I didn’t know much about Lautner<br />

when I stumbled upon this house, but I knew I<br />

wanted it. Someone else had it under contract, and<br />

when he tried to renegotiate the purchase, I stepped<br />

in and bought it. When I was ready to start work-<br />

ing on the house, I brought Lautner in to see it. He<br />

was shocked to see what had happened to it. One of<br />

the previous owners had just destroyed the place—he<br />

painted the concrete ceilings green and yellow. So we<br />

worked together for almost 15 years before he died,<br />

and I think he was really thrilled with the opportunities<br />

I gave him. As far as I know, it was the first time<br />

he was given the opportunity to design furniture and<br />

really work on the entire house, inside and out, and<br />

bring it up to its full potential.<br />

BLASBERG: Was redoing the house an expensive<br />

undertaking?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: I never gave Lautner any budgetary<br />

constraints. It was always a case of, What is the best<br />

possible way to do this?<br />

BLASBERG: No budget at all?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: Never. I still don’t have a budget on<br />

that nightclub addition. Whatever it takes.<br />

BLASBERG: So tell me, is this house your full-time<br />

occupation right now?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: My business cards say FASHION<br />

ARCHITECTURE BASKETBALL. When people ask me<br />

what I do, they’re usually trying to ask how I made<br />

my money, not what my job is. In my mind, what I do<br />

is those three things. They occupy most of my time:<br />

fashion, going around to all the fashion weeks and<br />

being such a fanatic when I pick out my clothes, trying<br />

to be in the latest fashions. Architecture, which<br />

you can see here, with this house. And basketball,<br />

which is another full-time occupation for me.<br />

BLASBERG: How much time could being a<br />

basketball fan take up?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: I go to about four or five games a<br />

week during the regular season here in Los Angeles.<br />

And then when the playoffs start, I’m on the road getting<br />

on an airplane every day for about seven weeks.<br />

BLASBERG: Were you always a Lakers fan?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: No! I’m not a Lakers fan. I consider<br />

myself an NBA fan because I follow every team equally. I<br />

just happen to live in L.A. I think that no matter where<br />

I lived, I would not be a fan of the home team. If everybody<br />

is favoring one team, I always go the other way.<br />

BLASBERG: But you still go to every single game?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: I don’t just go to the games in L.A.<br />

The playoffs are such an exciting time in my life. I’ve<br />

gotten recognition as being the number-one basketball<br />

fan. But I don’t do it for the fame—my basketball fame<br />

evolved by accident. I just went because I enjoyed it so<br />

much. The same thing happened in fashion.<br />

BLASBERG: How would you describe the way you look?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: First, I’d say I don’t want to look like anyone<br />

else, but I want to do it in a tasteful, stylish way. I want<br />

to stay up with the latest possible styles, so that every season<br />

I do my utmost to find something that’s new, that’s<br />

never been done before, but that’s in tune with the latest<br />

style, whether fabrics or exotic skins. When it comes<br />

to my look, I want to be as trendy as possible, and at the<br />

same time, I want clothes that look good on me. I feel<br />

that I’ve been able to maintain my figure pretty well.<br />

BLASBERG: Do you ever say how old you are?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: In recent years, I haven’t disclosed<br />

my age.<br />

BLASBERG: Well, it’s true that probably only a<br />

young man would want a nightclub in his backyard.<br />

GOLDSTEIN: Exactly.<br />

BLASBERG: What are you going to stock the bar with?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: Everything.<br />

BLASBERG: What do you drink when you go out?<br />

GOLDSTEIN: I don’t drink alcohol. I drink fresh<br />

juice. That’s my secret.<br />

FASHION DETAILS<br />

3.1 PHILLIP LIM 31philliplim.com • 8 88 EAU DE<br />

PARFUM BY COMME DES GARÇONS barneys.com<br />

• ADAM KIMMEL adamkimmel.com • ALEXANDER<br />

MCQUEEN alexandermcqueen.com • ALEXANDER<br />

WANG alexanderwang.com • ANN DEMEULEMEESTER<br />

anndemeulemeester.be • ANLO anlo-nyc.com • APRIL77<br />

april77.fr • ARIAT ariat.com • ARMANI JEANS armanijeans.<br />

com • AUDEMARS PIGUET audemarspiguet.com •<br />

AUDIO-TECHNICA audio-technica.com • BALENCIAGA<br />

balenciaga.com • BANANA REPUBLIC bananarepublic.<br />

com • BILLYKIRK billykirk.com • BLISS LAU blisslau.<br />

com • BOSS ORANGE hugoboss.com • BOTTEGA<br />

VENETA bottegaveneta.com • BUMBLE AND BUMBLE<br />

bumbleandbumble.com • BURBERRY PRORSUM burberry.<br />

com • BURBERRY THE BEAT burberrythebeat.com •<br />

CALVIN KLEIN COLLECTION calvinklein.com • CALVIN<br />

KLEIN HOME calvinklein.com • CALVIN KLEIN JEANS<br />

calvinkleinjeans.com • CALVIN KLEIN UNDERWEAR<br />

cku.com • CÉLINE celine.com • CESARE PACIOTTI<br />

cesarepaciotti.it • CHANEL chanel.com • CHLOÉ chloe.com<br />

• CHRISTOPHER KANE net-a-porter.com • CHRISTIAN<br />

DIOR dior.com • CLINIQUE clinique.com • COMME<br />

DES GARÇONS doverstreetmarket.com • CONVERSE<br />

BY JOHN VARVATOS converse.com • COVERGIRL<br />

covergirl.com • D&G dolcegabbana.com • DAVID SAMUEL<br />

MENKES davidmenkesleather.com • DIESEL diesel.com •<br />

DIOR BEAUTY dior.com • DIOR HOMME diorhomme.<br />

com • DKNY dkny.com • DOLCE & GABBANA<br />

dolcegabbana.com • DRIES VAN NOTEN driesvannoten.<br />

be • ELIE TAHARI elietahari.com • EMPORIO ARMANI<br />

UNDERWEAR emporioarmani.com • ERMENEGILDO<br />

ZEGNA zegna.com • ERES eresparis.com • FALKE falke.<br />

com • FENTON fentonusa.com • GAP gap.com • GIORGIO<br />

ARMANI giorgioarmani.com • GIVENCHY BY RICCARDO<br />

TISCI givenchy.com • GUCCI gucci.com • GUISEPPE<br />

ZANOTTI guiseppe-zanotti-design.com • H&M hm.com •<br />

HELMUT LANG helmutlang.com • HERMÈS hermes.com<br />

• HUGO hugoboss.com • ISETAN isetan.co.jp • J BRAND<br />

jbrandjeans.com • JEAN PAUL GAULTIER jeanpaulgaultier.<br />

com • JEAN SHOP worldjeanshop.com • JENNIFER BEHR<br />

jenniferbehr.com • JOHN VARVATOS johnvarvatos.com •<br />

JOHNNY FARAH johnnyfarah.com • JOSEPH joseph.co.uk<br />

• KARL LAGERFELD karllagerfeld.com • KIWON WANG<br />

kiwanwang.com • LACOSTE lacoste.com • LACRASIA<br />

lacrasia.com • THE LEATHER MAN theleatherman.com •<br />

LE MALE BY JEAN PAUL GAULTIER jeanpaulgaultier.<br />

com • LEVI’S levi.com • L’HOMME BY YVES SAINT<br />

LAURENT yslbeautyus.com • LISELOTTE WATKINS<br />

lundlund.com • LOEWE loewe.com • LOOK FROM<br />

LONDON lookfromlondon.com • L’ORÉAL loreal.com •<br />

LOUIS VUITTON louisvuitton.com • M.A.C. maccosmetics.<br />

com • MAISON MARTIN MARGIELA maisonmartinmargiela.<br />

com • MAISON MARTIN MARGIELA ARTISANAL<br />

maisonmartinmargiela.com • MARC JACOBS marcjacobs.<br />

com • MAX MARA maxmara.com • MCQ by ALEXANDER<br />

MCQUEEN alexandermcqueen.com • MENDED VEIL<br />

mendedveil.com • MIU MIU miumiu.com • MISSONI<br />

missoni.com • NARCISO RODRIGUEZ narcisorodriguez.<br />

com • NICHOLAS KIRKWOOD nicholaskirkwood.<br />

com • NICOLE MILLER nicolemiller.com • NIKE nike.<br />

com • NOTORIOUS BY RALPH LAUREN ralphlauren.<br />

com • OLIVER PEOPLES oliverpeoples.com • OPENING<br />

CEREMONY openingceremony.us • OSCAR DE LA RENTA<br />

oscardelarenta.com • OSKLEN osklen.com • PALMER<br />

AND SONS palmerandsons.ca • PAUL SMITH paul<strong>smith</strong>.<br />

co.uk • PIAZZA SEMPIONE piazzasempione.com • PIERRE<br />

HARDY pierrehardy.com • PORTS 1961 ports1961.<br />

com • PRADA prada.com • PRINGLE OF SCOTLAND<br />

pringlescotland.com • PROENZA SCHOULER<br />

proenzaschouler.com • RAG & BONE rag-bone.com •<br />

RALPH LAUREN COLLECTION ralphlauren.com •<br />

RALPH LAUREN WATCHES ralphlaurenwatches.com •<br />

RAQUEL ALLEGRA raquelallegra.com • ROCAWEAR<br />

rocawear.com • ROLEX rolex.com • RUFSKIN rufskin.<br />

com • SALVATORE FERRAGAMO salvatoreferragamo.com<br />

• SCHOTT NYC schottnyc.com • SHAMBALLA barneys.<br />

com • SOCK DREAMS sockdreams.com • SWAROVKSI<br />

ELEMENTS crystallized.com • TABITHA SIMMONS<br />

tabithasimmons.com • TIFFANY & CO. tiffany.com •<br />

TOM FORD tomford.com • TORY BURCH toryburch.<br />

com • UNIQLO uniqlo.com • VALENTINO valentino.<br />

com • VERSACE versace.com • VERSENSE BY VERSACE<br />

versace.com • VISVIM visvimshoes.com • VIVIENNE<br />

WESTWOOD viviennewestwood.com • WOLFORD<br />

wolford.com • YIGAL AZROUËL yigal-azrouel.com •<br />

YOHJI YAMAMOTO yohjiyamamoto.co.jp •<br />

YVES SAINT LAURENT ysl.com<br />